It was a strange feeling. Suddenly, I was asked to become the subject of someone else's art-making. And not just to sit for a portrait in the usual sense of the word. Portraits are usually fairly straightforward affairs, either commissions or records of friends and colleagues. Artists tend to use their fellow artists as subjects because they esteem them, share creative time together (such as Edouard Manet painting Monet working in his studio-boat) or even, sometimes, because they need an inexpensive model. But my request to be the subject was a little different, I learned.

Read MoreManet

Creativity /

Everyone uses the word. Everyone feels that intuitively, they know what "creativity" means. Everyone also knows that it is a highly desirable quality to possess. Yet the definition of creativity is not so easy. The Oxford English Dictionary succinctly puts it as "The use of imagination or original ideas to create something; inventiveness." Wikipedia gets broader in concepts: "' the production of novel, useful products' (Mumford, 2003, p. 110). Creativity can also be defined 'as the process of producing something that is both original and worthwhile' or 'characterized by originality and expressiveness and imaginative'." The article goes on to add that there are countless other versions of definitions.

Of course, in the art arena, creativity is deemed indispensable if the artist is in any way to be successful. Yet, as we all know, there are so many versions of artistic expression that most are considered creative only by a few viewers. Only the truly exceptional are heralded by most people, and until very recently, the culture of each country also played a part in the degree of appreciation of the work created.

What set me off thinking about the concept of creativity was a wonderful expression I read in a marvellous new book, "The Churchill Factor" by Boris Johnson (Mayor of London Boris Johnson). Discussing Winston Churchill's amazing abilities, particularly in the World War II period, Johnson says, "he (Churchill) also had the zigzag streak of lightning in the brain that makes for creativity."

It is so often just that aspect, the "zigzag streak of lightning in the brain", that allows for unorthodox approaches, solutions that come out of left field, images configured in a wholly novel way, vivid writing that none else has achieved.

In art, for instance, every generation has had truly creative people who have broken out of the mould and done things differently. The Renaissance was full of artists - think, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Durer, Titian - developing linear perspective, depicting landscape in naturalistic fashion, executing portraits of people in realistic fashion, modelling with light and shade. Later generations perfected oil painting, shifted the focus of Western art to Mannerism - such as Tintoretto or El Greco. Then the Baroque artists flourished, like Caraveggio, Rubens or Rembrandt, and on the artists marched. Look at some samples of the different ways artists worked down the centuries.

By the 19th century, art needed some more innovatively creative artists and the Impressionists came to the fore, with Manet, Monet, Renoir and Pissarro leading the way. Creativity certainly flourished with Gauguin, Van Gogh and Cezanne, as they laid the groundwork for 20th century artists to find entirely new paths to follow in creating art in tune with their tumultuous century.

Perhaps another aspect of creativity as it zigzags through the human brain is that it very often has, as a springboard, the social and cultural context of the time. To me, creativity is partly a spontaneous phenomenon arising in some wonderfully imaginative human mind, but it is also like a seed that has been planted in soil fertile and well watered enough for the seed to germinate, grow and flourish so that others see and appreciate it.

Only when Churchill was at the helm during World War II could his multifaceted creativity flower so successfully as he led his country out of peril and to victory in 1945. In the artistic world, the Leonardo da Vincis, Titians or El Grecos needed the powerful patrons of the land and Church to enable to give successful expression to their creative skills.

Later artists have had a harder time finding patrons and supporters to allow them to create and to live decently, a situation known to most artists at one point or another. And does creativity flourish as fully and successfully when the artist is worrying about the next meal or the next rent payment? In every field, from art to architecture to engineering or technology, the same considerations pertain - how to ensure the optimum conditions so that human creativity can flourish. In truth, our collective future depends in large part on that zigzag flash of creativity in the human brain.

Art from the Garden /

It is enough to make one feel guilty!

Spending hours in the bright sunlight in the midst of winter, while practically everyone one knows is suffering extreme cold or torrential rains or both in rapid succession in Northern countries.

Winter in the Mediterranean has definite charms.

One of the most delightful of these charms is a part of the garden fragrant with a carpet of violets blooming. Every time I pick these lovely flowers, I remember the steep banks of Tanzanian mountain terraces bound with violets where I spent hours as a child picking huge perfumed bunches while my mother worked among the flowers in the terrace beds.

So it was natural that when I moved to Paris, I was delighted to find there were still ladies selling bunches of flowers on street corners and especially posies of Parma violets, the most fragrant of all violets, said to be from Toulouse.

And then I discovered the paintings and drawings of flowers that told of other people’s delight with violets down the ages as I spent hour upon hour in the French museums.

The love of violets showed up early, not surprisingly, in the wonderful margin illuminations in medieval manuscripts, where flowers are woven in with birds, insects and glorious arabesques and curliques. Since violets symbolize purity, modesty and pure love and are associated with the Virgin Mary, it was normal to include these spring flowers in Books of Hours and other religious works. Books of Hours were created from the 13th century onwards, often in France, and are still treasured works that remain jewel-like. Nonetheless, violets had come into the Christian lexicon from far earlier: the Greeks hadesteemed them and used them in sleeping draughts, health-giving tisanes, as sweetening for food, as well as loving their beauty. The Romans of course followed suit, and made wine from violets, used them in salads and as conserves. Violet tinctures and elixirs, perfumes and cosmetics helped restore health and well being. Later the Anglo Saxons believed in the curative powers of violets for wounds, and followed ancient practices of using violets to help restore the respiratory tract after colds and bronchitis. So it was not surprising that violets very so frequently illustrated in early holy books.

Individual early artists who celebrated violets, members of the Viola family, are Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo da Vinci.

Then came a long period when violets, and other flowers for that matter, were mostly painted by Dutch still life artists in the 16th and early 17th century.

It was really not surprising that the Dutch artists should celebrate flowers but they became masters of combining flowers, in one painting, that actually bloomed at entirely different times. Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1583-1621) was one such master, painting on panels or on copper, works that glow.

A little earlier, French writer, traveller and artist, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues had teamed up with the French Huguenots who unsuccessfully attempted to establish a colony in Florida in 1564, recording much of the flora and fauna he saw there. He also later worked in London and produced some beautiful botanical studies, considered the finest in the 16th century. He included violets in his repertoire.

The French heritage of botanical studies continued into the 18th and 19th century, as is demonstrated by Pierre Jean François Turpin, considered one of the best botanical and floral artists of the Napoleonic era and beyond, as well as another noted German botanical illustrator, Georg Dionysius Ehret. Another Frenchman who painted violets in a less rigourously botanical fashion was Paul de Longpre (1855-1911): he was very much into the Victorian era spirit of depicting flowers. Nonetheless, he know how to paint violets in a way that allows one almost to smell their perfume.

Wood Violet, Pierre Jean François Turpin, (1775-1840), (Image courtesy of Musee National d'Histoire Naturelle)

Indeed, the 19th century brought more attention to the humble violet, mainly as a prop in portraits of young ladies, as in Théodore Chasseriau’s and James Tissot’s cases.Edouard Manet obviously got enticed by bouquets of violets, for in the same year, 1872, he painted two pictures, on a study of a bunch of violets, the other a portrait of Berthe Morisot with a bunch of the same flowers.

The Victoria era brought a surge of interest to flower painting and the violet was one of the favoured flowers to paint, with its symbolism, fragrance and, I suspect, availability as Viola odorata varieties grow beautifully in well-watered, moderate to mild climates. The French and British artists seem to have been the most keen on painting violets, but in the United States, in the early 20th century. Lila Cabot Perry used violets in a couple of her paintings. Elbridge Ayer Burbank and Thomas Waterman Wood were other American artists who loved violets, as was the Tiffany artist, Alice Gouvy.

Today, artists still turn to the violet family in delight.

One only has to look on the Net at the many, many images, mostly photographs, of these lovely flowers. But perhaps, in anticipation of 14th February at the end of this week, this should be the last image about one of my most favourite flowers, one of them growing in a garden. One can just imagine their perfume scenting the air.

Happy Valentine’s Day, everyone!

Attitudes about Flower Painting /

I have always been interested to listen to the "intonations" with which people speak or write about flower paintings. Floral art has often had a difficult time ascending high on the ladder of art appreciation, in circles of art officialdom.

Despite flower painting having illustrious beginnings from the 16th century onwards, with Northern Renaissance Dutch and Flemish artists, flower painting has historically been associated with amateur lady painters who pursued art as a pleasant, genteel past time. Very few male artists have painted flowers as their main subjects - Manet, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh and other 19th century artists did some wonderful paintings of flowers, very much as still life. This painting done in 1883 by Edouard Manet is a perfect example.

Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase, Edouard Manet, 1882, (image courtesy of the Musee d'Orsay).

Henri Fatin-Latourwas one of the most amazingly passionate painter of flowers, again as still life. These artists did however observe the flowers carefully and closely, and knew how these plants grew.

H. Fatin-Latour, White Roses, 1875, (Image courtesy of York Art Gallery, York, UK)

Other later male artists, from Picasso to Matisse and beyond, occasionally painted or drew flowers, but often, the results were more generic.

Matisse, Flowers, 1945

Meanwhile, women artists were creating beautiful "portraits" of plants and flowers, many using the botanical approach as their springboard.

Ellis Rowan was travelling through Australia and South East Asia in her quest to paint brilliant and exotic flora. Perhaps the conscious or unconscious links between gardening and flower paintings in British circles helped foster the interest in such art in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa as well as Great Britain.

Carolina Jessamine, Gelsemium sempervirens, Ellis Rowan

Another wonderful result of celebrating a garden was the art Childe Hassam created in Celia Thaxter's garden on the Isle of Shoals, Maine. This is one such painting Hassam did in 1890, now in the Metropolitan Museum.

Celia Thaxter's Garden, Childe Hassam, 1890, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Despite all these - and many, many other - instances of superb floral paintings, I cannot help being aware of a certain tone when such art is talked to in today's art world. Almost a sneer, not quite? As if paintings about flowers are, really, not quite "up to snuff". Despite a huge renaissance of botanical art (mostly done, need I say, by women artists), despite the trail blazed so memorably by Georgia O'Keeffe with her sensual, strong interpretations of flowers, there is still a je ne sais quoi in the air on the subject of floral art.

G. O'Keeffe, Two Calla Lilies,1928 (Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

This attitude fascinates me because, as I struggle to draw or paint flowers, I realise, repeatedly, that tackling flowers as a subject is very complex. In fact, just as challenging a subject as nudes, landscapes or anything else that are considered more "serious". By the time that an artist has mastered the intricacies of plants, their flowers and leaves, he or she is pretty capable of tackling any other type of art subject imaginable, and in any medium..

Maybe the decades when drawing was considered unnecessary contributed to the dismissal of flower-based art. Perhaps today's emphasis on conceptual art also is a factor, with the overtones of floral paintings lacking "gravitas" and deeper meanings. It is however ironic that part of the art world is so dismissive of floral painting, because another, large part of the art-loving world is very happy to embrace it.

Just as well, I conclude. Think what complexities and delights artists would miss if they never looked closely at a flower!.

Flowers in Art /

After a week of much colder weather, the flower garden is definitely in winter mode, save for a few brave camellias now venturing to bloom again. They are one of the most beautiful aspects of Southern gardens for me, and I can never plant enough of them, particularly the whites and pale shell pinks.

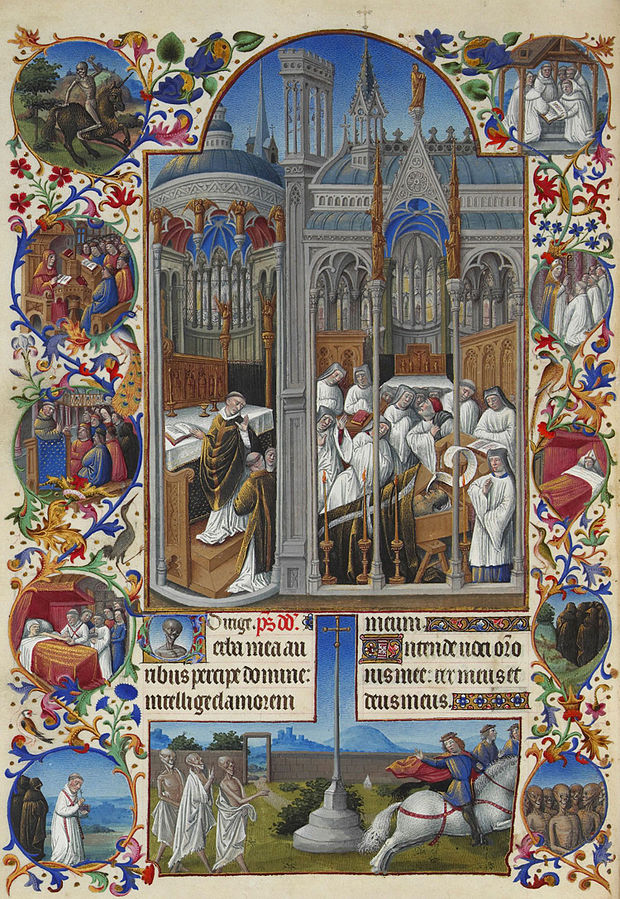

Since there is so little variety outside, I have been going through flower paintings in my mind's eye. This was made all the easier as I have been thinking about medieval times, when religious texts were becoming more and more luxurious, with an increasing demand for Books of Hours by wealthy patrons. Many of these jewel-like small creations are bedecked with the most wonderful depictions of flowers, many of them with floral symbols to underline the religious truths of the texts. An introduction to some of these images, with colours glowing and flowers ranging from pinks to violets, asters, forget-me-nots, daisies or roses, shows that by 1410, artists were producing the most amazing Books of Hours for patrons such as Catherine of Cleves, Flemish or French nobility.

Produced in the Netherlands in about 1460, this Book of Hours is from the Euing Collection. University of Glasgow

Perhaps the most famous is Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, painted from 1412-1416 almost exclusively by the three Limbourg brothers, Paul, Henri and Jean. Interestingly, there are not many details of flowers, but even here, in one image of a Funeral Service, campanula wander amongst the text on one column.

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. Folio 86, verso: The Funeral of Raymond Diocrès, between 1411 and 1416 and between 1485 and 1486

By 1500, the use of flowers in Books of Hours was widespread, as can be seen in this edition done in Rouen, France, held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Palma's Book of Hours, silverpoint and watercolour, Jeannine Cook artist

I created Palma's Book of Hours, done in silverpoint and watercolour, thinking of the tobacco/nicotiana as the flowers opened and closed each day in a rhythm which marked off the hours for me in perfumed regularity.

Another early devotional book, the Wilton Diptych, was created in England c. 1395-1399, for the purposes of accompanying its rich travelling owner. In one scene, pink roses adorn the angels' heads, but apparently they were originally the red Rosa Gallica, one of the earliest known rose varieties.

Richard II presented to the Virgin and Child by his Patron Saint John the Baptist and Saints Edward and Edmund (‘The Wilton Diptych’), Anonymous, ca. 1395, egg on oak, 53 x 37 cm, National Gallery

Detail of the Wilton Diptych

Detail of the Wilton Diptych

An image of this can be found, amongst others, on a wonderful web page on the BBC. This site depicts a wide variety of flower paintings down the ages and it underlines the continuous attraction for artists of flowers, in their beautiful diversity and elegance. This is hardly surprising when one thinks that we humans have always known flowers - they have been in existence for about 120 million years. Fascinatingly, they have apparently always played a central role for humans - archaeologists have found a burial site for a man, two women, and a child, in a cave in Iraq. They were Neanderthals, living in these Pleistocene caves. On this burial site had been placed a bunch of flowers.

The Greeks placed great store on flowers, such as violets and had them in their houses and wore them in crowns at feast times. The Romans did the same and held festivals of flowers to honour the goddess, Flora. Remember the fresco uncovered in Pompeii of Flora and her flowers. Roses were the flower of the goddess of love, Venus; roses too have always been celebrated by Confucians and Buddhists.

The early Renaissance artists loved to depict lilies in Annunciation scenes - Fra Filippo Lippi was one of the early ones in 1450, for instance. Leonardo da Vinci did the most exquisite drawings of Regale lilies. You can almost feel the weight of the flowers as he studied them and drew them in pen and ink. The Pre-Raphaelites also loved lilies - on the BBC site I mentioned earlier, there is a reproduction of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's "Annunciation" with the lilies the most graceful complement. Then there is the wondrously atmospheric John Singer Sargent painting, "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose", done in 1885-6, with the children and beautiful tall, proud lilies in the luminous twilight.

The seventeenth century was also the heyday of Dutch flower painting, done by both men and women. One of the most successful was Rachel Ruysch, while another was Judith Leyster, who did some silverpoint drawings of tulips. Flemish-born Ambrosius Bosschaert was one of the first to specialise in flower paintings and others like Jan van Huysum and Jan Bruegel followed his footsteps with looser, often more brilliant styles. Since a lot of the Dutch flower paintings were also about Holland's wide-flung world power and dominance, as well as the flowers' beauty, the artists did not hesitate to mix up flowers from all parts of the world, which would never bloom at the same time. They composed the most astonishing mixes in their arrangements, requiring a lot of time and ingenuity to pull the complex compositions together.

France forged a different approach to flower painting. Pierre Joseph Redouté began his highly talented life as a flower painter under Queen Marie Antoinette's patronage, but the Empress Josephine hastened to continue the patronage after the Revolution. His wonderfully sensitive "portraits" of flowers and plants are so realistic one can almost smell the perfume, for instance, of his roses, and he managed also to combine careful science with astonishing art. He helped pioneer a whole sub-group of botanical artists whose numbers, today, have swelled amazingly and fruitfully throughout the world. Take a look at the American Society of Botanical Artists' website, for instance - I am proud to be a member of the burgeoning Society. (Dr. Shirley Sherwood, of London, has been one of the major supporters of this renaissance of botanical art, and now her collection is not only showing in many venues around the world, but also at Kew in a permanent, dedicated gallery.)

The second half of the 19th century produced some wonderful flower painters in France - Manet did some exquisite studies of flowers in vases, while Henri Fatin-Latour became famous for the way in which he painted roses and peonies, larkspur and other wonderful summer flowers. He would wait until the roses almost dropped their petals, so as to be able to capture that ultimate fullness of musky beauty in each petal. Monet delighted in his flower garden, culminating with the glories of Giverny and his lily pond, while Renoir and Degas were no slouches in their depictions of chrysanthemums, geraniums and other plants. Of course, everyone knows about Vincent van Gogh and his passionate sunflower paintings – he had moved far from the exquisite jewels of medieval flower painting, but left all of us the richer for both approaches. Odilon Redon comes to mind too for his pastel studies of flowers that were far beyond just the botanical and yet are brilliantly evocative in their somewhat strange feel.

The twentieth century seems to have always had its lovers of flower paintings. An interesting note I saw was that 55% of all art considered "decorative" and available today is floral art. No wonder there was a reaction against flower paintings in juried shows for a long time! Nonetheless, a lot of us artists have continued to celebrate flowers in art - they are just too important to ignore, and besides, when a garden is in the depths of winter, at least one can evoke warmer times by having paintings or drawings of flowers on the walls.

Playing /

I listened with fascination this morning on National Public Radio to a programme, Play, Spirit and Character, on Krista Tippett's show, Speaking of Faith, which talked of playing and its importance in life. Stuart Brown was being interviewed. His wisdom and insights on how animals and humans need to play, in infancy, childhood and adulthood, were fascinating. It is well worth seeking out the interview on the Web.

As Stuart Brown talked about playing, I realised how important playing has always been as I tried to create art. Every time that I want to experiment, to push out boundaries, to improve as an artist, I have always regarded the experience as play. I had not measured, apparently, the vital role play has in daily life, let alone in art. Licence to do something different, unusual, amusing, distracting, lively - these are all versions one can find in the Oxford English Dictionary as definitions, amongst many, of play. Freedom too is a definition. In other words, play is an integral part of one's creativity as an artist: without it, one is liable to be stultified, stuck and dull. Oh!

Think of Manet, Monet, Cezanne, the Fauves, Matisee or Picasso, amongst so many artists - they all show a sense of play in their work, and those works usually herald changes and break-throughs in their development. To say nothing of the spirit of play that one sees among many of the most successful artists of the 20th century, many of whom definitely do not or did not take themselves or the world around them too seriously. It was good to have it reaffirmed in the radio programme today that one needs to play, every day, in all the realms of one's life, but especially in art.

Fishing Boats, Collioure, 1905 , by Andre Derain

The energy of art /

During a visit to South Carolina to see the recently-opened exhibition from the Davies Collection, National Museum Wales, Turner to Cezanne, at the Columbia Museum of Art, I was struck afresh at the energy and magic created by art.

Not only was the exhibit a delight, with small canvases of great interest and often great beauty, but the whole experience of seeing the show was fascinating. The exhibition galleries were thronged with excited, but well behaved school children being taken around by docents. Their energy and fresh reactions to the art were a delight to be a part of as one looked at the art more slowly than they were able to. In amongst the school groups were numerous adults, clearly enjoying and appreciating the exhibition too. Why did I find this so striking ? Well, apparently this is the the most important show the Columbia Museum of Art and its supporters have brought to the city, and despite the current economy, the response from the public has been massive. In the first week already, the museum has seen huge numbers of visitors, both local and from elsewhere.

To me, the public excitement generated by this exhibition reminds one again how art brings people together and strengthens communities. By the time my husband and I had emerged from the museum, we had talked to countless people and even exchanged addresses with new friends. Each painting in the exhibition, from France mainly, but also from England, Wales, Belgium and Holland, quietly or dramatically "spoke" of different landscapes and places, different people and their mores, diverse optics on life in general - all a wonderfully subtle and beguiling way of learning of other lands, their history and culture. Each artist, whether it was Turner, Monet, Van Gogh, Manet, Pissarro, Whistler, Renoir or Cezanne, passionately told of their experiences and convictions, beauties and visions.

Jospeh Mallord William Turner Margate Jetty, National Museum of Wales

People were smiling, obviously interested and learning, marvelling at different aspects of the art. In other words, the visit to the exhibition moved visitors, made them feel better and made their day special.

What a perfect prescription - go to see an art exhibition to make one feel energetic, inspired and even joyous!