The coronavirus pandemic has hit everyone very hard, but artists seem to be low on the totem pole of governmental help. A simple, direct drive to purchase art and in turn, that artist purchases other artist’s work is one venture recently launched on Instagram to help. Generous and a way to celebrate art.

Read MoreMetalpoint

Confinement and the Artist /

Corvid-19 confinement is a time of great ironies, it seems. Enormous stress and tragedy contrast with astonishing abundance of ways to occupy one’s hours of isolation. For me as an artist, I am beginning to feel that some of the contrasts are a little overwhelming.

Read MoreThe Artist Residency that Wasn't /

When an artist residence proves different from what is expected, it pays to try and be flexible and resilient, and, of course, keep on making art!

Read MoreRecurrent Themes in An Artist's Work /

Olive trees are an integral part of the Mediterranean landscape, and they have been a recurrent theme in many artists' work. Sacred trees since early Greek times, they are astonishing in inspiration, as well as generous in their fruit and oil. No wonder artists love to celebrate these astonishing and often very ancient trees.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 2) /

Part 2 of a long look back at the heritage of landscape and plein air art that we artists enjoy today nd from which we can draw encouragement and inspiration, as well as instruction.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 1) /

As plein air artists, we are standing on the shoulders of artists who were lovers and orbservers of nature from many centuries ago. This is a celebration of some of these artists in their depictions of the landscape.

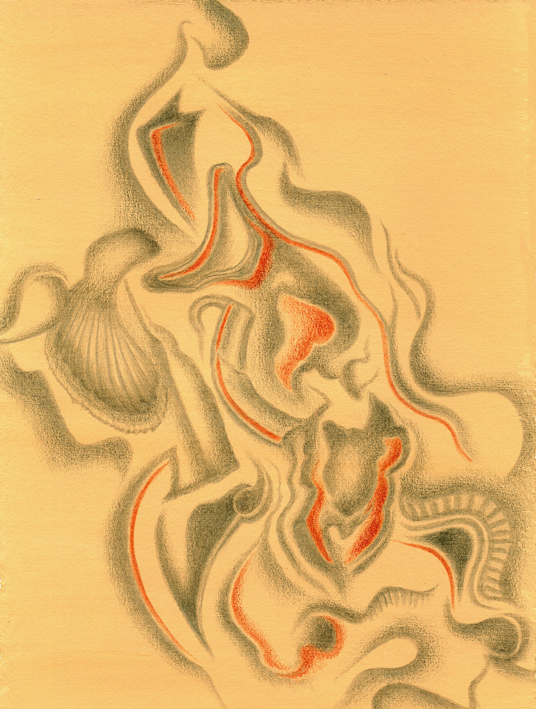

Read MoreBurgundy Drawings /

Ammonites de Bourgogne, silverpoint, watercolour, Jeannine Cook

It is done – I have managed to produce 15 drawings for the exhibition at the Musée de Noyers! What a relief! I deliver them next Monday and the exhibition will run concurrently with the show I have hanging at the gallery at La Porte Peinte.

Preparing for an exhibition under deadlines is never a favourite occupation for any artist. However, some people do work best like that. I am not sure that I do – the results of the effort will be for others to judge!

What has been both interesting but also more complex has been the need to weave together a body of work that pertains to the ideas I put forward originally, namely the birth of metalpoint drawing in the scriptora of monasteries, where monks used lead to delineate the illuminations and trace lines for the script of their illuminated manuscripts. Combined with that history, I wanted to celebrate the tiny fossilized oyster shells found in the Kimmelridgian layers of soil found especially in the Chablis area and which contribute to the special terroir of those wines. I had picked up samples of these heavy stones when I first arrived in Burgundy last year, and they have led me on a fascinating odyssey.

Tying the metalpoint’s history together with the fossil-laden stones was thanks to those industrious monks who in medieval times also helped to spread the cultivation of wine, as they founded the great monasteries in Burgundy. Vezelay, Fontenay, Pontigny: they are all centers of such a rich heritage.

Even the wonderful and mighty plane trees, such as one sees at Fontenay that was planted in 1780 by the Cistercian monks, ten years before they had to leave their monastery, was part of that long-standing monastic heritage that enriches us all.

The other aspect that I tried to incorporate into these drawings is the close links between Burgundy and ocre, one of the key pigments in man’s artistic endeavours since the earliest marks man-made on cave walls from Australia to Africa to Europe. Burgundy was famous for its yellow ocre deposits and only ceased to produce ocre pigments in the 20th century. By heating yellow ocre, red ocre is produced; the two pigments find their way into every drawing and painting imaginable down the ages. I used the two colours as tinted grounds for some of the drawings I did for this project. Since early times, some artists used tinted grounds for their metalpoint drawings, so again, I was following a long-standing tradition.

I loved finding out all sorts of things about history and aspects of beautiful Burgundy for this project. It has been such fun - the drawings have been the perfect vehicle and excuse for all sorts of new insights and investigations. It is marvellous when art and fresh knowledge can go hand in hand.

Burgundy and Art /

It is hard to believe that the days can flash past so quickly, but I have spent four full days already here at Noyers sur Serein at La Porte Peinte for the first part of my artist residency. I flew to Paris and drove across a world of wondrously wide and luminously golden harvested cereal fields. La belle France! The home front finally has calmed a little, with health stable and so I was able to slip away to come here. The exciting events since I arrived – I hung my artwork as part of the overarching exhibit, Quotidiaen, here at the La Porte Peinte gallery. It is metalpoint work that I did as a result of my residency last year which I framed for exhibiting and brought with me. My part is entitled Les Pierres qui Chantent: Dessins en Pointe de Metal.

The other exciting news is that indeed I will be able to exhibit work that I am currently producing in the Noyers Museum in September. I am also preparing an informal talk about it all and about metalpoint in general for the Journées de la Patrimoine in September, when France’s wonderful patrimony is celebrated.

So thanks to all my generous friends who helped me reach the Hatchfund funding goal for this residency atLa Porte Peinte, I am organized!

Now, of course, has come the other aspect of this venture – producing artwork. I have been working hard, perched in my magical eerie above the cobbled main square in Noyers, with the sounds of French, mingled with laughter, that drift up to the open window. The delicious swallows are still flying ceaselessly, calling and swirling as they dart in to feed their babies in their beautiful mud nests attached to the medieval oak beams of the porches and roofs. As I am high up, I see the flash of their white rumps and black wings in their aerial ballet beneath me – the perfect accompaniment to metalpoint’s black and white.

I have just finished the third in the initial series of the project drawings – Burgundia – as Burgundy was named from Roman times onwards. I have tried to marry the main themes of the project together – fossilized shells, metalpoint, wine and the “horror vacui” of medieval manuscripts with their lettering in brilliant colour and details of nature covering each page. I managed to photograph one drawing – with complications – as normal scanners will not reproduce all the “whispered” lines in silver. The others will have to await my return home!

Step by step, line by line – what fun!

Forms of Still Life /

Inching my way back from the roles of hospital companion and guardian to my husband as he recovered from an emergency operation, I finally felt I could slip back into my artist world a little. It was a welcome move as there is nothing more debilitating, for patient and family, than sojourns in a hospital. My first treat to myself was to see a recently opened small exhibition at the Museu Fundacion Juan March in Palma de Mallorca. Entitled "Things: The Idea of Still life in Photography and Painting", it straddled 17th century Dutch still life paintings and late nineteenth-early twentieth century photographs.

It was a really interesting premise, examining the forms of still life and even the cultural differences in the use of the word, "still life". The German and English versions of the words echo the original Dutch/Flemish concept of examples of things that are faithfully recorded in a carefully organised composition. But the Spanish "naturaleza muerta" or 'bodegon" stray far from the original premise. Most of the work presented represented northern artists, thus closer to the true sense of still life.

The Dutch paintings were lovely small ones, where the artists had delighted in the play of light on a glass goblet or a small ceramic dish, spoon or the crisp glint of a peeled lemon.

The leap to the early medium of photograph to record still life that, mostly, was pre-composed, was interesting. Sometimes, the photographs seemed airless, compared to the paintings, still a characteristic of many photographs today when compared to paintings. Yet there was an elegance and refinement in the photographs that were distinctive. As always, I seem to prefer the very simple compositions - such as one by Baron Adolphe de Meyer taken in 1908 of two hydrangea flowers in a glass of water, the reflections of the glass playing out on the wide expanse of the surface in the lower third of the photogravure.

The selection of photographic still life works was wide-ranging - from daguerreotypes to a coloured autochrome coloured back-lit plate of flowers by the Lumiere Brothers done in 1908, a circa 1895 trichromatic print of flowers (so much for all our modern "inventions" of technicolour) and then into the more modernist 1920-60 black and white work by Man Ray, Walker Evans, and many other European photographers.

Every interpretation of still life was there one could imagine - from carefully set up compositions, to views of life made still in abattoirs or after a volcanic eruption to Walker Evans spotting a natural still life scene on a back porch of a (sharecropper?) weather-beaten clapboard house.

As I looked at the different compositions and the elements that made up those compositions, mainly derived from nature, I could not help realising that most of my current artwork is, de facto, still life. I am using elements of nature in compositions that record stones, bark, flowers --stilled by being placed in a setting other than their original one. I have only strayed a little, like many other artists, from the path of still life "inventor" artists of the seventeenth century by cropping, zooming in on some elements and eliminating others, framing and thus altering the original concept and layout of the still life set up.

I love feeling this sense of kinship and heritage that comes when you look at artwork from previous times and understand how and why you do things the way you do, thanks to those earlier artists.

Thoughts on Crowdfunding for Art Projects /

You certainly learn by doing! I decided to do a crowd-funding project on Hatchfund as an experiment, to push out frontiers as an artist and hopefully to give good publicity to a very worthy cause, the artist residences at La Porte Peinte, in Noyers, France.

The first frontier I had to extend was getting into video-making, an area I had not yet visited. I met charming video-makers and although the first video was not what I hoped for, simply because I was utterly inarticulate with 'flu at the time, the second was better because I was more coherent and able to talk.

I am fascinated with the idea I developed - namely to try to marry together the metalpoint monastic heritage that flowered in Burgundy and elsewhere, the wine-producing heritage there and the extraordinary fossilised oyster shells found in stones lying in some Chablis vineyards. It will be a really interesting challenge to weave these strands together into viable art. I suppose that is what art residencies are for - peace and time for experiments!

However, the other, and perhaps most time-consuming, aspect of my crowd-funding venture has been the actual fund-raising. I clearly had not thought through all the implications of such a project. Nonetheless, I soon found myself sitting down and writing to friends and supporters who have been wonderful enough to collect my art over the years.

I have to say the results have mostly been heart-warming and gratifying. There have of course been days of nothing at all happening, no one even acknowledging my e-mails, but then, out of the blue, comes a short e-mail from Hatchfund saying that such and such a person has supported the project.

Slowly the figures have crept up, until two days ago, I realised with a shock that I had passed the magic threshold mark of the minimum amount needed to fund the project and thus release the funds to me. What a relief!

En route to that point, I have learned a few aspects of this crowd-funding world. The first is distinctly cultural: I realise that a British background of not blowing one's own trumpet and not putting oneself forward does not prepare one well for the necessary soliciting of funds. Americans seem to have no such problems. The second is that the American way seems to require a considerable amount of outright hucksterism, two-for-the-price-of-one department. I think one has to be selective in approaches, depending on the type of project one is trying to promote.

The third and last consideration I have found to be interesting. In an era that supposedly has everyone fully converted to and comfortable with on-line financial transactions, there is still a high proportion of people very reticent indeed about putting a credit card on-line. Cheques still retain a high degree of reliability and safety to many people and on-line fraud is a very real threat.

However, towards the end of the Hatchfund fund-raising period on my Art Residency at La Porte Peinte, I am beginning to feel that it has been a good thing to have done. Mostly because it has given me reason to touch base with friends and supporters with whom I might not have exchanged news and greetings until later in the years. Also too, such a project, willy-nilly, forces one to measure oneself out there in the big, wild world -- and it is always nice to find that it is possible to bob along and keep afloat in the choppy waters of competition.

Thank you all, my generous supporters. And to my other friends from whom I have not heard, I hope to hear from you, especially to hear that your summer is going along happily.