A violinist continuing to produce beautiful museum despite broken strings, artists creating astonishing work in the face of many forms of adversity - all examples that give us hope an encouragement for these strange times in which we are living in 2020;

Read MoreHenri Matisse

Recurrent Themes in An Artist's Work /

Olive trees are an integral part of the Mediterranean landscape, and they have been a recurrent theme in many artists' work. Sacred trees since early Greek times, they are astonishing in inspiration, as well as generous in their fruit and oil. No wonder artists love to celebrate these astonishing and often very ancient trees.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 4) /

The 19th century saw a flowering of plein air art in Europe and in this part of my blog-series on Plein Air Art - Looking Back, I had fun trying to select images that could celebrate this explosion of energies and talent. We owe a great deal to those artists as they broke with academic tradition and painted as their hearts dictated.

Read MoreGolden Globes - Oranges in Art /

Looking at the glowing oranges hanging in such bounty from the trees in the garden, I find myself marvelling in the play of light on their rough skins and the intensity of the colours. The lustrous dark green leaves are the perfect foil for the fruit, the brilliant Mediterranean blue sky above the ultimate enhancement. The temptation to paint these oranges is constant, but I have learned that watercolours are not the best medium to convey the intensity of these glorious winter fruits.

I began thinking of the paintings I have seen over the years of oranges; I realise that of course, it is mostly artists who have lived in the Mediterranean area - or at least visited - that have used oranges in their paintings. One of the earliest artists that comes to mind who used oranges in a wonderful still life painting was Spanish Francisco de Zurbaran (1598-1664). I was spellbound, like so many others, when I saw this painting at the Norton Simon. It glows - and the oranges could almost be smelled in their tangy citrus perfume.

Another Spanish artist that comes to mind celebrates oranges in a different fashion - oranges growing in orchards or being sold: Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida, Valencia-born artist of light and Spanish life, straddled the 19th and 20th century, and recorded history, landscapes, portraits in vivid, lyrical fashion.

Another artist who loved the brilliance of oranges in the South of France was, of course, Vincent Van Gogh. He returned to these golden marvels several times, and I am sure their colour not only echoed the golden yellows he loved so much in sunflowers, ripe wheat fields, or his chair, but they must have cheered him up when he was in mental anguish.

Paul Cezanne used them too in some of his still life paintings. One of the most famous is a complex feat of celebrating fruits, including the oranges.

Apples and Oranges, Paul Cezanne, c. 1899, (Image courtesy of Musee d'Orsay)

At almost the same time, Henri Matisse was also experimenting with still life paintings that included oranges. It was a theme to which he returned...no one can resist these golden orbs!

Every time I walk in the garden and see the oranges, I understand why these artists used them in their brilliant still life studies.

The Whole Composition /

A visual artist always has a set of decisions to make at the beginning of a work - how to compose the picture, what to emphasise, what to convey by the way the picture is composed. That is in part why so many people advocate doing thumbnail sketches before embarking on a painting or drawing; one needs to work out a sensible road map, a composition that works.

Henri Matisse once remarked, "I don't paint things. I only paint between things." He paid close attention to the relationships between objects and how they relate to the whole composition. In a way, he was, in essence, creating an abstract web and underpinning to the composition by looking at the negative spaces, versus focusing on the "things".

Still Life with Geraniums, Matisse, 1910 (image courtesy of the Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich)

Look, for instance, at this Still Life with Geraniums which Matisse painted in 1910. There is a wonderful, energetic structure going on thanks to the contrasts between the horizontals and verticals and the organically curvaceous objects and flowers. Half-closing your eyes and looking at the negative spaces in the painting leads to a really strong, dynamic underpinning to the work. Yet there is also a sense of space and airiness that was one of Matisse's great skills. His paintings looked out, not inwards in a hermetic fashion.

In the same way, the 1912 painting, The Window at Tanger, relies heavily on the relationships between the sense of space and spaciousness and the "things". (The image is courtesy of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.)

The Winndow atTanger, Henri Matisse, 1912, (Image courtesy of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.)

The deep blue knits everything together, but flattens the space into a near-abstract image. Matisse visited Morocco in 1912 and again in 1913, and the bright colours and flat perspective show the influence that Islamic art was having on Matisse. He had already brightened his palette considerably with his Fauve period, so it was a logical development to embrace the brilliance of the Moroccan world. He used the "differences" in this scene from his hotel window to knit together an enormously evocative and energetic composition.

Another very different approach to the concept of composing a picture by concentrating on the spaces between objects can be seen in Rembrandt's prints. When he was working on his etchings, he was so technically skilled that he could fade out the contours of objects he was depicting and allow the "differences between things" to evoke the desired effect. Seventeenth century Italian art historian and connoisseur, Filippo Baldinucci, remarked, "that which is truly noteworthy of this artist (Rembrandt) was his remarkable style that he invented to etch in copper - that is, loose hatching and irregular lines and without contours he succeed in making profound contrasts."

Rembrandt's 1654 etching, The Descent from the Cross

Rembrandt's 1654 etching, The Descent from the Cross, is one example. Few contours, wonderful spaces between "things" and an arresting composition all are rendered more powerful by this technique that Baldinucci described.

The Woman before a Dutch Stove, Rembrandt, 1658 etching

In the same way, the spaces between, so expertly depicted and so vital to the composition, are masterfully achieved in this 1658 etching, The Woman before a Dutch Stove.

For every artist working now, it is always rewarding to go back and study attentively what has been done by the great artists of the past. The Internet helps greatly in allowing us to see these images, but there is, even now, a huge difference between these digital images and the actual artwork. That is when seeing how Matisse actually applied paint to the canvas as he evoked those relationships between things, or peering at Rembrandt's etchings, with their amazing hatching, through a magnifying glass, allow us to see the artist's hand and deft, skilled touch. Those details allow the ultimate consolidation and achievement of the composition, the relationships of things one to the other and thus to the whole work.

Play /

As the old year wanes and there are these few final days during which to think about the incoming New Year, I suddenly remembered a little statement that I had caught during the fascinating PBS film, A Murder of Crows. It seems something important to remember - for me, at least - as 2012 dawns.

"Play allows the mind to develop and thus the crows become more creative." I think that pertains to us all, corvids, humans, and everyone in between.

Dance, Matisse, 1909-1910, (Image courtesy of the State Hermitage Museum)

As artists, it is so important to play, to revert in a way to a childlike mental state, to relax. Every time I remember to do this, I find that the art I am trying to create seems to flow better.

Think of some of Henri Matisse's dancers; here, he seems to have distilled his art to a marvellous sense of joyous play. Above is a second version of Dance that Matisse did in 1909-1910, the version now in the State Hermitage Museum . But then fast forward to 1947, when Matisse had to resort to paper cut-outs, papiers coupes, because his infirmities precluded him from painting. He still retained a sense of play, and his creativity was undimmed.

Icarus (Jazz), papiers coupes, 1947, (image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

How more eloquent an example of play allowing creativity to flow can one get! The crows can certainly teach us a lot. So can Matisse!

Happy New Year to all, and joyful play.

Life Experiences and Art /

Pablo Picasso was of the opinion that "a painter should create that which he experiences".

As one goes along in life, there are plenty of experiences that mark one, positively and negatively. As an artist, there are times when you can "digest" an experience fairly quickly and it will show up in your art in a relatively straightforward fashion. Perhaps the most direct way to depict experiences pictorially is plein air painting or drawing. You are filtering through onto paper or canvas your sensory experiences of an area, urban or rural, coastal or upland, whatever.

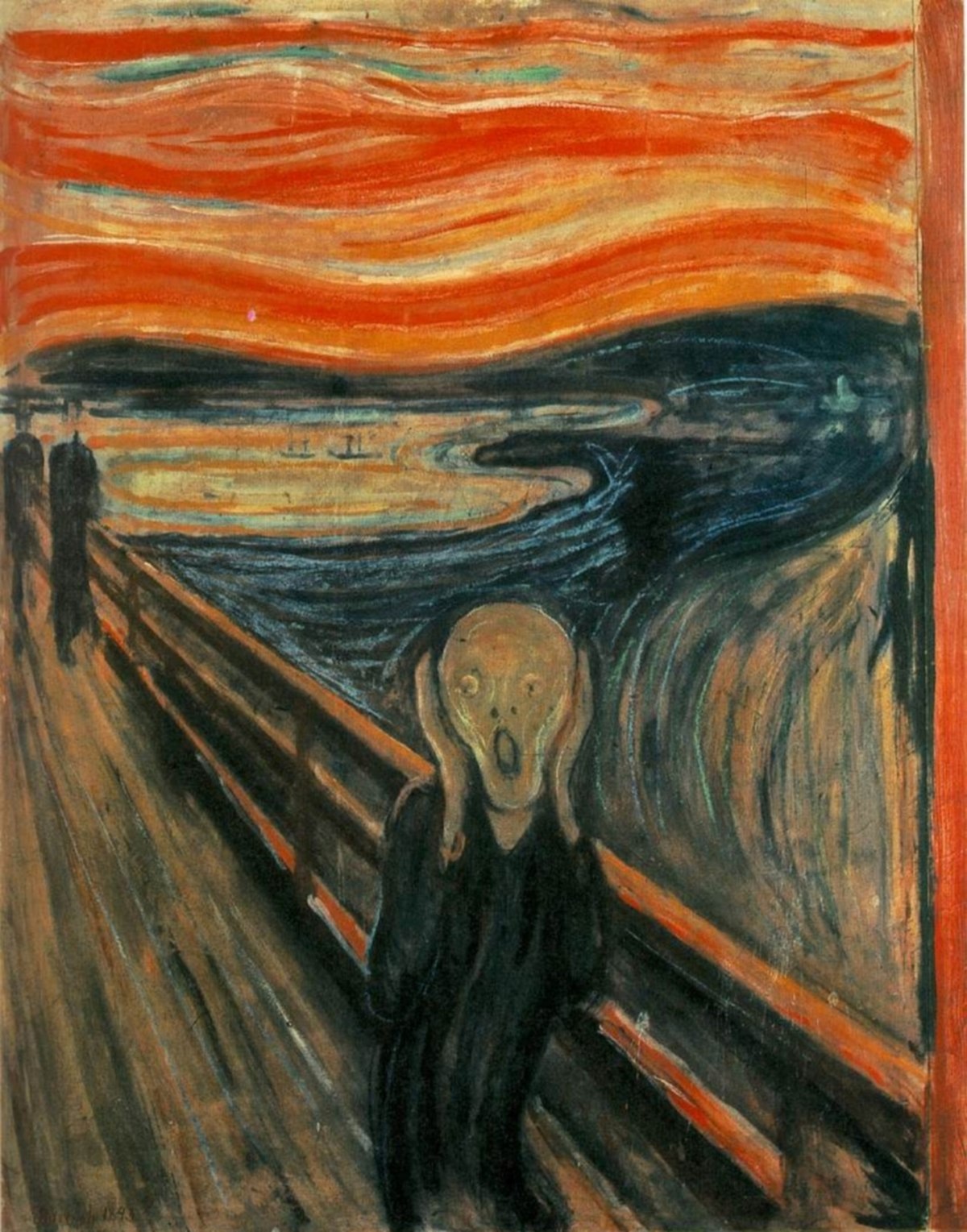

When an artist's life goes through major ups or downs, those experiences are more complex, but sooner or later, they do seem to show up in a serious artist's work. Perhaps one of the most famous examples of art arising from life experiences is The Scream which Edvard Munch painted when he was 30 years old.

The Scream,Edvard Munch, oil, 1893, (Image courtesy of the National Gallery, Oslo, Norway

He had had a very difficult life from childhood. He wrote about his father, "My father was temperamentally nervous and religiously obsessive - to the point of psychoneurosis. From him, I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow and death stood by my side since the day I was born." By the time he had moved to Berlin and then to Paris, experimenting with different artistic styles, he was coping with deep anguish and angst. He later said about this painting that, "for several years, I was almost mad. I was stretched to the limit - nature was screaming in my blood. After that, I gave up hope ever of being able to love again."

Picasso spoke very accurately of his art being derived from his experiences. His Blue Period paintings were influenced by the suicide of his friend, Carlos Casagemas. His love affairs with his various mistresses were the source of the amazing work that continued to flow from him during his long and productive life. Borrowed experiences are also sometimes the source of great art. Again, Picasso is a prime example, with Guernica, which was created after the Germans bombed the small town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War.

Guernica, Pablo Picasso (Image courtesy of the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid)

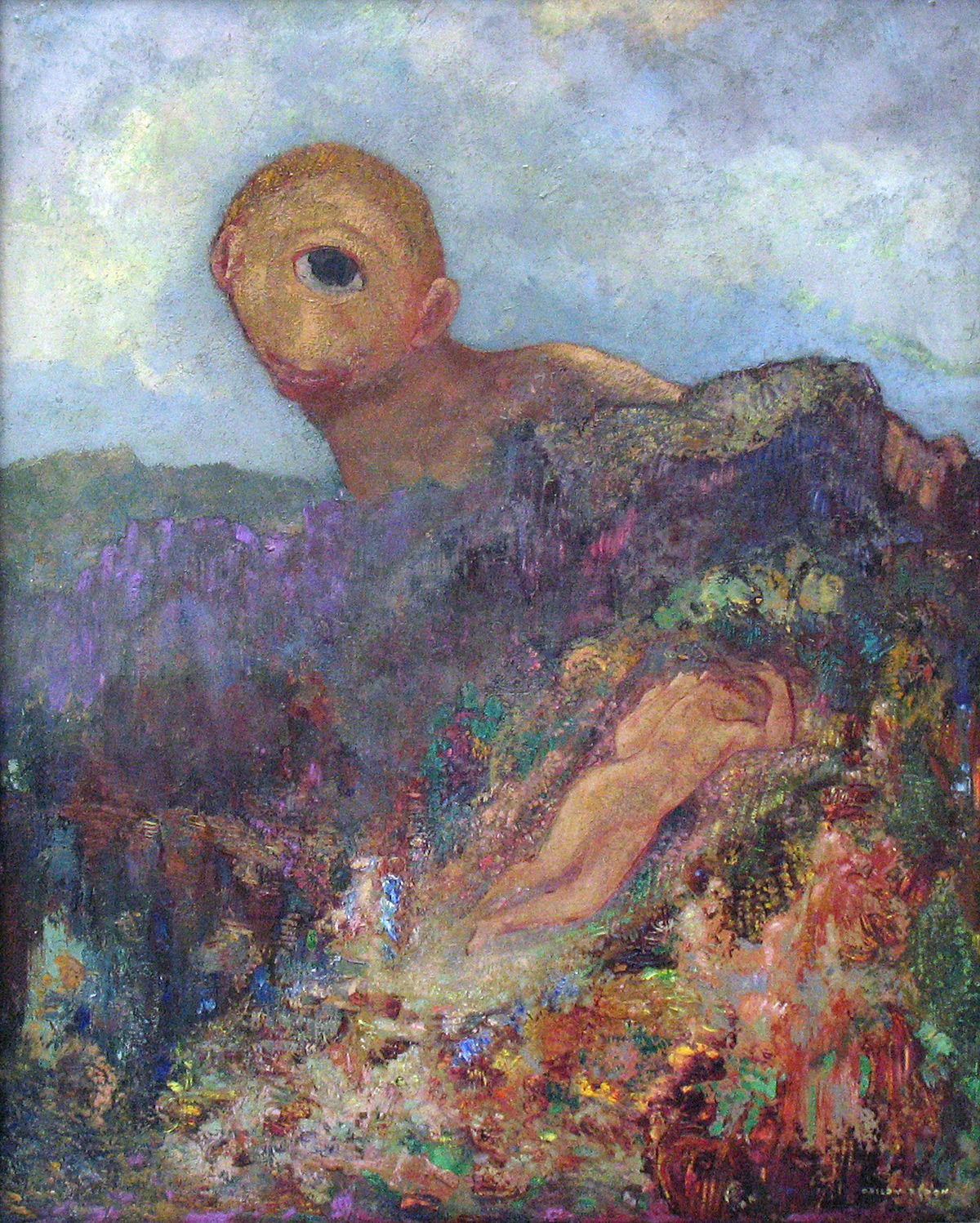

Other artists believe in placing "the visible at the service of the invisible", as 19th century Symbolist Odilon Redon said. His inner experiences were channeled into strange pastels and paintings which often had an initial appearance of real subjects, but then then veer into the grotesque and ambiguous.

The Cactus Man 1881, Odilon Redon, Charcoal on paper (Image courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, New York )

The Cyclops, 1914 by Odilon Redon. Symbolism. mythological painting. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.

The Cactus Man (1881) is one of Redon's strange drawings. But there is a consistency that runs through his work, for in 1914, he paints The Cyclops . One can only conjecture at the personal experiences that drive these works of art.

Another type of experience that led to wonderful art is when Henri Matisse was increasingly unwell, towards the end of his life, and was confined to a wheel chair after 1941. So he turned to "painting with scissors" and produced his wonderfully joyous cut outs, his Blue Nudes from 1952 and his limited edition book, Jazz, with its series of colourful cut paper collages, amongst others.

Blue Nude with her Hair in the Wind, 1952, gouache-painted paper cut outs, Henri Matisse (Image courtesy of www,henri-matisse.com)

Today's artists have such a wide array of examples of how artists drew on their personal experiences to inspire their art. It makes a very strong case for each of us to believe in ourselves as artists, to listen to our inner voices and follow their inspiration into creating strongly individual art.