After the many glorious days of cloudless skies and brilliant sunshine, today was cloudy and grey. A bit of a shock, in a way. The change in the light and the sense of space was marked.

Skies, for an artist involved in any depiction of the natural world, are so important. Their role in setting a tone, a mood in any painting or drawing, is key. As a child of Africa, where the vast skies arch brilliant and endless, I love the wide vistas across the salt water mashes of coastal Georgia because here too, the sky is so expansive. Such views allow a sense of liberty, an expansiveness of soul that are allied to a sense of the infinite vastness of nature, of space and those countless galaxies far beyond our world. All these feelings are often filtered through the art one creates, in spite of oneself. In essence, it is "painting about something", versus "painting something". Whether the something is the light, the space, or much more complex philosophical concepts, the sky is central to the art making.

The painting below is the famed Deadham Vale 1802 depiction of rural England, where Constable used the sky to set the whole tone of the landscape, to flood it with northern light and give it a gentle expansiveness that is memorable.

Dedham Vale with Ploughman, 1814, John Constable, (Image courtesy of Scottish National Gallery)

John Constable RA, Cloud Study, Hampstead, Tree at Right, 1821. (Image courtesy of the Royal Academy)

John Constable believed that the sky was "the key note, the standard of scale, and the chief organ of sentiment" in a landscape painting. This 1821 Cloud Study, (above) a plein air study, is an example of his famed quick art done to record skies and weather conditions.

Despite the ever-increasing divorce between man and nature that we are witnessing today, there are still many artists who are enthralled - nay, obsessed - by skies and the wonders of light, clouds and atmospheric effects. Graham Nickson, the British-American artist who is Dean at the New York Studio School since 1988, had a wonderful exhibition at the Jill Newhouse Gallery in 2009, entitled "Italian Skies".

Graham Nickson, Sarageto III, 2008 (Image courtesy of Jill Newhouse Gallery)

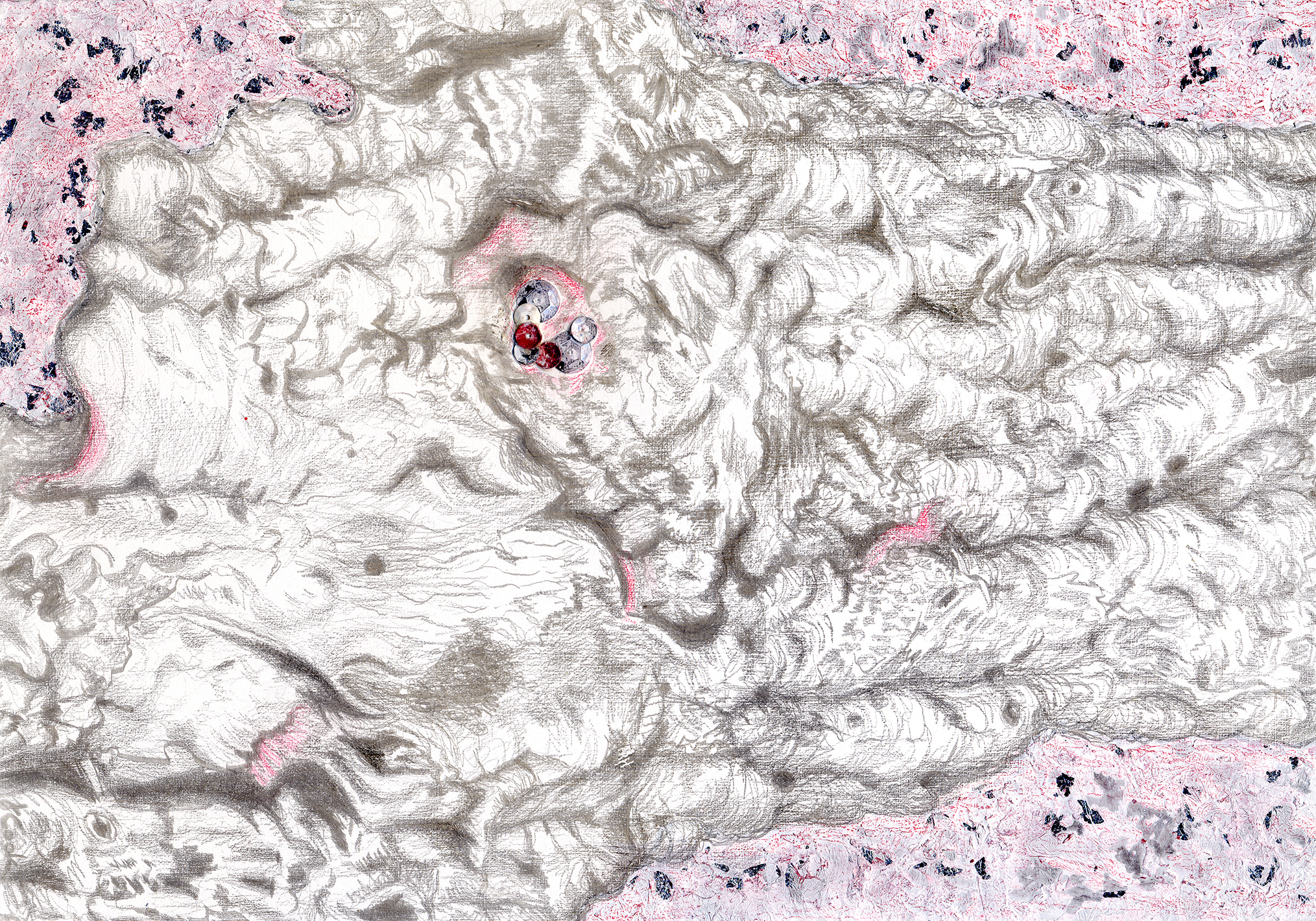

Jeffrey Lewis, who teaches are at Auburn University. He works in encaustic, and his series of paintings are lyrical in the extreme.

Towards Ontario mirus caelum, Jeffrey Lewis (Image courtesy of the artist)

Towards Ontario Vespers, Jeffrey Lewis (Image courtesy of the artist)

He speaks eloquently about the emotions that these skies inspire in him and what he seeks to convey in his paintings.

Towards Ontario Eventide, Jeffrey Lewis (Image courtesy of the Artist)

Photography too is a wonderful medium to celebrate skies, the light that emanates from them, and thus also the passage of time. One artist who has devoted much of her life to exploration of these subjects is Erika Blumenfeld, a Guggenheim Fellow and photographer. She discourses at length about such research and work in a recent fascinating interview with Art Interview, and clearly shares the same deep awareness of skies and their influence on all of us below their domes.

Background - Sky Scrolls, Erika Blumenfeld photographer (Image courtesy of the artist)