In Part 3 of Plein Air art - Looking Back, I follow the development of plein air art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe as so many artists paved the way for present-day interpretations of nature and the outdoors.

Read MoreWilliam Herschel

Single-mindedness /

I recently alluded to a wonderful book I am reading, The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes, about the 18th century Romantic generation's discoveries and accomplishments in science, exploration, literature and many other disciplines. The account of astronomer William Herschel's sister, Caroline, interested me deeply. She must have been a pint-sized (about five foot in height) force, highly intelligent and extremely self-disciplined. She was her brother's invaluable astronomical assistant, noting down all his observations as he peered through his wonderful telescopes at outer space, night after night. During the day time, for countless years, she ran his house, kept accounts, received eminent visitors and made the necessary calculations to complete William's observations.

However, in due course, she herself became a fully fledged astronomer, with her own beautiful telescopes which her brother designed and made for her. With single-mindedness, she began to sweep the skies, looking for comets. Like her brother, she became sufficiently familiar with the patterns of the night sky that she could almost "sight read", and thus more easily spot anything different. She became famous as the first lady astronomer, discovering a number of comets and garnering respect and acclaim in the international scientific community. She was also awarded the first professional salary every paid to a woman scientist in Britain when King George III granted her an annual stipend for life. Her single-mindedness, during those long, lonely nights spent looking through her telescope, brought her not only personal satisfaction, but much deserved respect.

Single-mindedness is an ingredient that I believe every creative person needs - whether in science, literature, art, music... Take a much respected and successful author, such as Robert Coram. His non-fiction books range from Boyd to American Patriot or Nobody's Child, while his fiction writing is extensive. His remark, during a lunch we were all sharing, was that for him, ten-hour days were followed by watching a film, by way of relaxation, before bed. That takes single-mindedness - ten-hour days, working on a project that normally takes about three years from start to publication. I mentally compared that with my time spent drawing and painting, and decided I needed to juggle personal and professional life more successfully!

I also had a reminder of another form of creative single-mindedness, as I listened today to NPR's Susan Stamberg talking about the current exhibition at the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery in Washington, The Art of Gaman. This is apparently an exhibition of the art and crafts created by the Japanese Americans interned in camps here in the United States during World War II. Since they were simply dumped in these camps with no more for each family than four walls, lit by a light bulb, a pot-bellied stove in a corner and cots, they had to fashion anything else they needed out of any scraps they could find. But they went further than just utensils and furniture. Their single-minded courage led many of them to create art, jewellery and other pieces which are now on display. "Gaman" in Japanese means the ability to "bear the seemingly unbearable with dignity and patience".

Bearing the Unbearable: The Art of Gaman , Iseyama teapot

Another manifestation of such single-mindedness was the art created by Jewish children and adults sent to Theresienstadt in World War II or, indeed, the drawings and paintings created in Auschwitz or Buchenwald or elsewhere. Think too of the dedication of those who were in Theresienstadt to composing and creating music. Faced with such appalling conditions, it must have required almost superhuman single-mindedness to continue creating beauty and uplifting manifestations of the best of the human spirit.

Patterns /

In my previous post about William Herschel, I mentioned that his ability to scan the night sky was helped by his knowledge and familiarity with music and more especially with sight-reading. Underpinning both skills was the honed ability to recognise patterns, and thus note any difference in those patterns, especially in the stellar nebulae.

In the same way, patterns are frequently a very important part of art-making. Nature is full of such examples, from alto-cirrus clouds to ripples on the water, from a millipede's many footprints in the sand to the distinctive feathering on a bird that flashes from tree to tree.

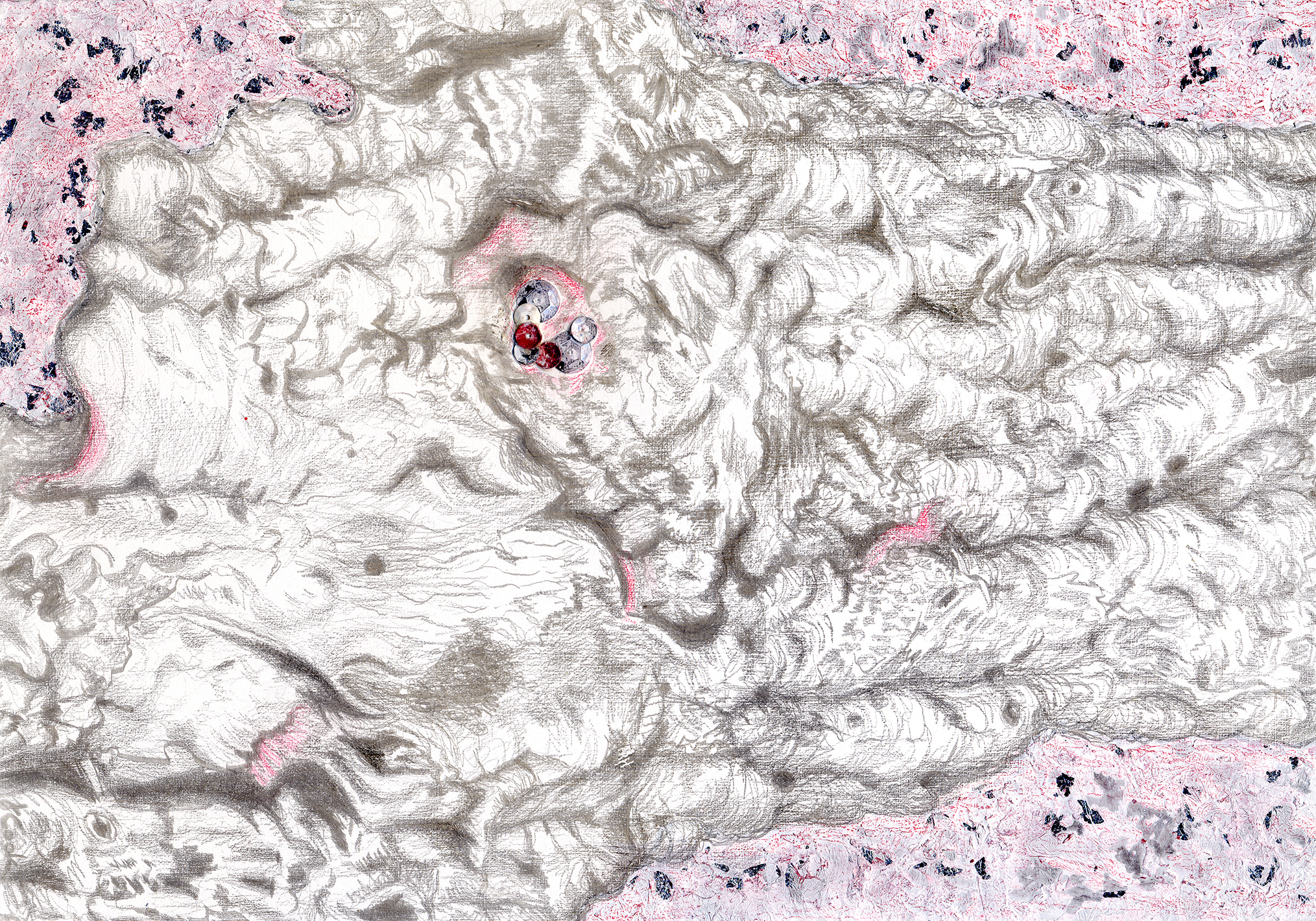

Tree bark offers a magical multitude of patterns, each distinctive to the tree species. The silverpoint, watercolour and sequins I used to depict The Life Within seemed appropriate for the live oak bark I picked up on a walk one day. Shaped by wind and rain, sun and shade, the tree's bark is a wonderful indication of the energy and resilience of that tree.

The Life Within, silverpoint, watercolour, sequins, Jeannine Cook artist

A walk along any beach yields countless examples of nature's patterns in shells. This silverpoint I did of an Angel Wing came from Sapelo Island. Its patterns show how nature reinforces the delicate shell to withstand the sea's relentless tossing and pounding. For an artist, it is endless fascination and a considerable challenge to draw!

Angel Wing shell, silverpoint, Jeannine Cook artist

Patterns play a huge role in many approaches to art. One type of work that I have always found powerful is Australian aboriginal art , in which their visual and Dreaming worlds are united. Patterns reach an apogee of complexity, beauty and subtlety in these paintings. . Dots, dashes, stripes - they become the ultimate collection of patterns, even though they are in truth symbols of their sacred Dreaming world. This is especially the case with the art produced from 1972 onwards in the North West Territory at Papunya, when the tribal elders began to paint on Masonite and later canvas, rather than on rock faces and sand, as they had done for the last 20,000 years.

MAWALAN MARIKA, Sydney from the Air, 1963, National Museum of Australia.

Another version of patterns in art was sent to me the other day by a fellow silverpoint

and graphite artist, Cynthia Lin, . It was the announcement of a current collective exhibition, Observant, at New York's ISE Cultural Foundation, in which her large-scale graphite drawings of skin are featured. This is one of her works, entitled Crop3 DSnosemouth (detail), 2008, graphite on paper, 66 x 71".

Whether realistic or abstracted, patterns are the underpinnings of most art. It is fun to observe nature's patterns and even more fun to incorporate them in art.

The Rewards of Practice /

In a marvellous and most fascinating book, The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes (Pantheon Books, New York , 2008), I have been reading about the eighteenth century astronomer, William Herschel.

William Herschel, 1785, oil, Lemuel Francis Abbott (Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery)

His extraordinary dedication to making better reflector telescopes and extending astronomical knowledge led to his being appointed King George III's Personal Astronomer. He discovered Uranus, the seventh planet and the first to be discovered since the time of Ptolemy, and became a most celebrated member of the Royal Society.

His original profession was not astronomy but music, which he learned mainly from his father in Hanover. He was a gifted musician, composer, and music teacher, who met with considerable success in England, especially in Bath. However, his passion was amateur astronomy to which he dedicated more and more time. And this is where I found it so fascinating: his prior skill in sight reading in music and his dedication to practice in music-making helped make him, he believed, a far better astronomer.

Some people claimed that his finding another planet was mere chance, and he reacted defensively. He wrote on 7th January 1782, "I do not suppose there are many persons who could even find a star with my (magnifying telescope) power of 6,450, much less keep it if they had found it. Seeing is in some respects an art, which must be learnt. (My emphasis). To make a person see with such a power is nearly the same as if I were asked to make him play one of Handel's fugues upon the organ. Many a night have I been practising to see, and it would be strange if one did not acquire a certain dexterity by such constant practice." (Again, my emphasis.)

Richard Holmes further wrote of Herschel's skill in identifying stellar patterns as being honed by his many years of sight-reading musical scores. "Or more subtly, the brain that was trained to recognise the highly complex counterpoints and harmonies of Bach or Handel could instinctively recognise analogous stellar patternings." (page 115)

This fascinating account drives home to me the value of practice in whatever artistic venture in which one is engaged. The eye, the ear, the hand and thus the brain all improve with constant training . Herschel was indeed a shining example of the virtues of practice.

The Age of Wonder is a marvellous book through which to be reminded of these virtues.