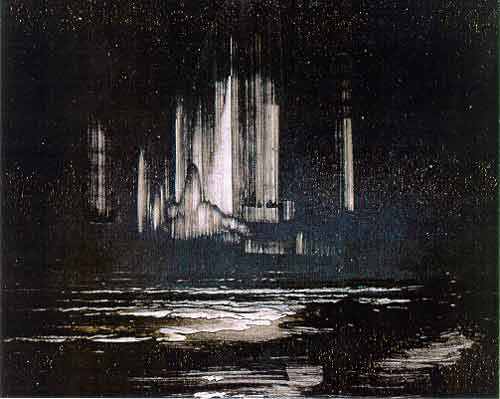

The Tempest, Peder Balke, 1862

Peder Balke is not the name of an artist that readily springs to mind, yet he is now considered the pre-eminent Norwegian artist of the 19th century. His landscapes and especially seascapes, highly unusual in their techniques, are now justly celebrated. I was lucky enough to see an exhibition of his paintings at the National Gallery, having seen a smaller one of his work in the same rooms four years ago. Balke lived from 1804-1887, started out as a full-time painter and then had to turn to other ways of earning his living. Nonetheless, he continued to paint, for his own pleasure, experimenting and using paints in ways that heralded modern expressionism. He travelled to the North Cape in Norway, an area of dramatic coastlines and radiantly strange light of the Arctic Circle. These scenes continued to influence him many years later. He did not always paint specific scenes, but used the moods and impressions of nature, often in almost abstract fashion, to convey the majesty, mystery, solitude and power of the natural world.

While the larger paintings on display in the National Gallery exhibition were impressive, especially the highly atmospheric ones of Northern scenes, done in the 1870s, the ones that fascinate me are the tiny ones. They pack a punch, almost in a visceral way.

They are indeed small, mostly blacks and white, seascapes and some landscapes of glaciers or waterfalls, often almost abstracts. They are not small, however, when it comes to impact. Their effect is perhaps more powerful than that of many of the larger paintings he did. Perhaps my love of monochromatic works leads me to them, but to me, they are stunning in their big voices coming from very small rectangles of oil on cardboard or oil on board.

I wonder if other people find them as arresting as I do?