Do you ever experience a wonderful moment when you see something in an exhibition, it suddenly resonates and explains some connection, or gives an unexpected insight into something else? I love those moments. I had a few such instances during my exhibition "orgy" in London recently. The first one came as I was marvelling at Goya's drawings in the superb "Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album" at The Courtauld Gallery. This exhibition was the first reconstruction of the dispersed 23 drawings from Francisco Goya's so-called Album D, "Witches and Old Women, produced during the wonderfully productive last decade of his life, together with other related drawings and prints.

The exhibition was riveting in every way - Goya's economy of drawing, his powers of depicting human emotions in their most raw and dramatic forms, his mordant commentaries on human foibles, all so simply done on small sheets of paper, in shades of ink - oh heavens! The scholarly work done that permits the reconstruction of this album, in a coherent and likely order of drawings, was also most fascinating and impressive.

Then, in the works accompanying the 23 drawings, there was a brush and brown ink drawing from Album B, Estas Brujas lo diran (Those Witches will tell).

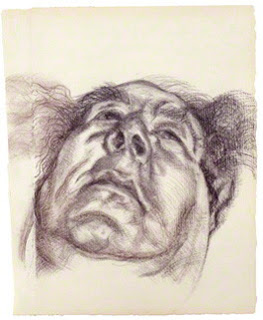

I was so astonished. The line from Goya ran straight and true to Egon Schiele's Self Portraits. Goya's drawing is a haunting image of a naked old witch devouring snakes. Egon Schiele's Self-Portraits tell of equally disturbing solitary states of mind.

Both artists are fluid in their lines, their vigorous treatment of wet and dry passages of drawing media. Did Schiele know of Goya's drawing in the Prado? Or was it just happenstance, the result of two gifted draughtsmen's states of mind?

Another "aha" moment for me that stands out in my memory was when I was looking at one of several unusual Claude Monet paintings in "Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market" at the National Gallery. In the gallery showing works by Monet that Durand-Ruel had exhibited in a pioneering monographic show in 1883, , there was an arresting painting of two apple tarts or galettes on wicker platters, Les Galettes, painted in 1882 and in a private collection today.

Its vigour and brio of treatment, its golds and yellows and close-cropped composition all take one straight to Vincent Van Gogh and his sunflowers or even a study of humble fishes, or bloaters. Did he see Monet's study of the Galettes - he most probably did, as he produced the first studies of cut sunflower heads some five years later.

The third moment of fascination for me was in the same Impressionist exhibition, again a Monet painting done in 1875, The Coal Carriers. Monet had seen workers unloading coal for the Clichy gasworks from the train from Argenteuil to Paris, and painted this work partly from memory.

The rhythmic placement of the men on the gangplanks, the silhouettes and dark colours somehow reminded me of many of the Japanese ukiyo-e prints, their rhythms and cropped views. Monet was an avid admirer of the new wave of Japanese prints coming in to Paris at that time.

I love these moments when you can link up artists, influences and inspirations. They validate one's own endeavours as an artist as you study and view other artists' works, not to copy, but to use as pathways to grow and spread wings.