Western Australian artist, Philippa Nikulinsky, is not only a superb botanical artist, but allies science, dedicated field observations and enormous skill to a passion for celebrating all the ecosystems of Western Australia. Her long years of art-making allow her to record the ever-changing landscapes, flora and fauna in a fashion that goes beyond environmental issues and political concerns, ultimately to achieve an incredible body of beautiful work that enriches Australia.

Read MoreAustralia

New Worlds: Spirit Drawings of Georgiana Houghton /

How many times do you go to an exhibition, especially in England, and end up talking to practically every other person in the room whilst looking at art? Not too often, I suspect! But that is exactly what happened as I went around a small and remarkable exhibition, "Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings" at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Each of us was so astonished and fascinated that we all talked to each other at one point or another, standing in front of a drawing, all of us marvelling at these pieces.

Read MoreThe Art of Facing Extreme Danger - Gallipoli, 1915. Part 4 /

Frank Anderson's 1915 Gallipoli diary continues recounting his experiences as part of the 10th Light Horse Regiment fighting in the Dardanelles.

Sunday, 8th August - "All day in the firing line, with no prospect of being relieved. We have practically no men here now, all being on our left where the battle has lasted all day." 9th August - "The night passed off quietly in our section, but the awful dim on our left made us ready for an attack any moment. The beach is covered with wounded waiting their turn to get aboard. We are all nearly knocked up having had no sleep for nights. No relief yet."

Wounded and Sick waiting to board boats in Anzac Cove

10th August - "We hear that they are afraid to let the Tommy take over the forward line of defence on Russells Top, so we are to man them indefinitely with the remainder of the Brigade or what is left of them. We are unable to get our dead in and it is heart-breaking to see all our fine fellows lying a few yards away, most of them horribly mutilated. We are all just about knocked out, and the Germans' 77 mm high explosives are damnable. Every day one or two men are hit. Bill Lyall was wounded last night. Amongst all the sadness it came out in orders that Arthur Irwin and myself had our commissions. Fighting continued all day on our left, mostly around hill 971. Wrote Baby the sad news of Dumpty."

11th August - "Today there seems to be a lull on both sides, but our vigilance is not the least slackened. All our supports have been withdrawn and are now on our left, so it will mean a fight to the last man if we are attacked. Water is getting very scarce and we are trying to live on 1/4 gallon of water a day. I have fortunately been been given A Troop and the men seem as pleased as I am. We are all filthy and need a wash badly. The smell from the dead is appalling but nothing can be done."

The next day was mostly quiet, "am terribly weary", and the same the following day, when everyone was consolidating positions and entrenching on both sides, he writes, "My night watch is from 2 a.m. to 5 a.m. and find it very hard to keep awake. Felt very seedy." On 14th August, "takes me all my time to crawl around. Felt rotten all day and during night. Bentley copped me in the trenches. He insisted on taking my temperature which was 103.5 so took me down to the surgery and said I had pleurisy, which I cannot credit. I think it is only weakness & want of sleep. Anyway he insisted on sending me, in the middle of the night, to the Field Ambulance on the beach, and they are to send me to a hospital ship in the morning."

"Was brought here early this morning on this floating palace hospital ship, the "Reva"." (16th August)

"I nearly fainted when a real live lady, in the neat uniform of the Red Cross, met me at the top of the gangway and gently led me down to the officers' quarters." From then on, Frank was cared for by these Red Cross nurses, who removed his filthy clothes, bathed him and gave him clean clothes. He recounted every detail of the arrival on the ship, the food, the pure white sheets, the utter delight of being in a civilised place after the hell of the trenches. Since his temperature would not go down for long, he soon found himself shifted to the "Andania", "a huge Cunarder", en route to Malta. Feeling in "a deplorably weak condition and rotten with rheumatism", he was told by the doctors on board that he would need at least three months to get him well again and that he was therefore being sent to England. In fact, Frank's hip had been broken during bombardments in the trenches, although no X-Ray could reveal that at the time, and he walked with a pronounced limp for the rest of his life.

Torpedo scares and rough weather on the trip to Devonport made the first days of the voyage trying, but by the time the ship reached Gibraltar, fair weather had calmed the sea. Soon cold weather made all his joints ache and the morphine kept him drowsy, but by the night of 30th August, he was being checked into the 3rd General London Hospital. That Hospital became his de facto home for the next year, as painful treatments were tried and his body slowly healed.

He was able to spend time out of the Hospital with his fiancee's cousin, Sophy Hassell, whom he had known pre-war. He began to get organised, contacting old friends and linking up with fellow officers to try and lead as normal a life as they could. Frank spent time in Saltash with Sophy Hassell and her friends. In London he was often detailed to accompany people to the theatre, some of them minor foreign royalty. He also took part in the first ANZAC ceremonies held at Westminster Cathedral. Whilst at the 3rd General, he took up photography, which was to be a lifelong passion. Some of his photographs included pictures of his nurses.

The long months of recuperation are not recorded in the 1915 diary, for Frank ceased to keep the account after September 25th. His progress was recorded a little in photographs.

Eventually, after a year in hospital, Frank Anderson was sent back to Western Australia, where he was demobbed, on crutches. On 24th July, 1917, Frank Anderson married his pre-war fiancee and great love, Honoria Ethel Hassell, daughter of a prominent grazier family in Albany, Western Australia.

Frank Anderson had survived one of the most brutal war campaigns of the 20th century. As I read his diary, I marvelled at his matter-of-fact statements about the awful situations and experiences. No complaints, no hand-wringing, just the stoic sense of duty to be performed, as best as possible. A spare elegance in his descriptions of events, an understanding of the fearful dimensions of the fight and a lucid assessment of the abilities of his fellow soldiers and commanders. In short, an impressive demonstration to me of an art form - how to live life as best as is possible under very trying circumstances.

The Art of Facing Extreme Danger - Gallipoli, 1915. Part 3 /

Frank Anderson's 1915 diary continues the entries about fighting with the 10th Light Horse Regiment, now at Russell's Top, an area which became know as The Nek.

6th August, Friday - "The attack is to come off to-night and we are all fearfully busy. At 5.30 p.m., the right flank attacked amid a tremendous bombardment but captured two lines of trenches. An awful fight lasted all night and news came through that the left flank was doing remarkably well."

Next day, 7th August - "We were called at 3 a.m. after a sleepless night and took up a position from where we were to charge. All the saps were crowded and confusion reigned supreme. The first line of attack was made up of the 8th as was the second. A squad and A & B troops formed the third line, the remainder of our squadron & C squad made the 4th line. We could hear a big battle going on to our left and we underwent a heavy shelling, which caused a good number of casualties and broke our trenches up considerably. At dawn the first line was ordered out but were mown down before they had gone more than 20 yards. From then on God only knows what happened.

"The trench was full of dead, dying & wounded, some of the second & third lines went out together, only to feed the enemy's machine guns. Still no orders came for us & the suspense was awful. Then the fourth and some of the third got over the parapets, but not one got more than 15 yards away and very few got back. In some remarkable way, Mr. Kidd's troop actually got over and only lost one man. I had no idea what my own troops' casualties were, but knew they were not very heavy. Then the order came to retire, and when we collected back on the Broadway, over half the regiment was missing. It was Arthur that first told me the news of D Troop being wiped out, then we heard of all the rest, Cmdt. Piesse, Mr. Rowan , Springall, Jackson, Dumpty (Frank's fiancee's brother), Phipps, Leo, the two Harpers, Barrycloc, Fenwick, Capt. McMasters, Lt. Hellon, Tom Burges, and in fact everyone that I seemed to know and like, were all dead. Craig, Jim Lyall & Bill wounded and a lot more. In my own troop, Eustace, Sandy & Chipper dead. Arthur and the few that got back had marvellous escapes. Was most anxious about Irwin but he turned up all right. In fact Pat, Arthur, John and myself seem to be the only ones left of our little clique. I can't realise it yet, but my nerves seem to have all gone. How I'll ever write and tell Baby (his fiancee, my grandmother) about it all, I don't know. It is all too awful.

"Major L. acted the coward, as we all expected he would, but the old Colonel was game and is immensely popular. After the first shock was over we started inquiring about our left flank and the sight that met our eyes in Anafagasta Bay was one never to be forgotten. A fleet of 8 cruisers & innumerable torpedo boats were heavily bombarding the Turks while a fleet of eight large hospital ships were in readiness. The transports were too numerous to count, but we could see that our men were gaining ground fast. The Turks had evidently got most of their troops reinforcing the position we attacked, with such disastrous results. But I believe we did our role and achieved more than was expected. We spelled until 4 p.m. almost exhausted, and we then took over the main firing line.

"Things were quiet for the remainder of the night on our immediate front, but the two flanks were fighting most desperately. During the night, the bodies of Mr. Rowan, Leo & Springall were all brought in. Phipps was got in before he died and had time to leave messages to Molly and his mother.

"And so ends the most terrible day I've ever experienced."

(Part 4, published next in this blog, will continue the account of Frank Anderson's experiences in Gallipoli, as recounted in his 1915 diary.)

The Art of Facing Extreme Danger - Gallipoli, 1915. Part 2 /

Along with A squadron, 10th Light Horse Regiment, Frank Anderson was shifted to Walkers Ridge, ("our new position is called Anzac") in early June. Water had to be fetched from 1/2 mile away and fireward very scarce. No mail either. "Wild rumours of every description. We don't even know the truth of our own position."

Despite being able to swim in the very cold water of the nearby bay, he reported catching his first lice, and being unable to sleep because of the extreme cold. By 18th June, the lice were "breeding in the most alarming manner.", while shell fire and shrapenel caused continual casualties, even down on the beach and in the water, where Frank had "a narrow escape" in one attack.

Long bombardments in the trenches killed more and gave everyone very "disturbed nights", in the great heat of mid-summer. "Water is getting terribly scarce and flies are awful." The food too became a great problem, with little fresh meat. Many men were constantly suffering from dysentery.

The war grinds on, with Frank having dysentery or food poisoning, busy plotting plans of the Australian positions, spending 24 hour stints in the trenches followed immediately by 24 hour stints sapping, By 7th July, "it has been ascertained that the Turks have got a supply of gases but we all have respirators and fear them not. Had charge of our section of trenches as Mr. Rowan (Frank's senior) is not well enough. The night was a very nervous one, and an expected attack did not come off." Next day, "there is a report about that cholera has broken out in the Turkish lines so every care is being taken here. Evidently the Turks have brought up some guns from Achi-baba and are giving us the advantage of them."

On 9th July, while in the trenches for 24 hours, "at 6 p.m. received instructions to proceed with Mr. Jackson to take accurate bearings of Snipers Ridge, for the use of the naval authorities. It was most risky work and we both narrowly escaped being sniped. The way our orderly room mutilates their messages is awful." On 10th July, "tried to have a swim but the snipers successfully kept everyone out of the water. The weather is getting hot again and as soon as Achi-baba is settled the better, as there is a tremendous lot of sickness." Cholera had indeed broken out among the Turks, so everyone was inoculated and felt very sore, compounding the sleepless nights waiting for attacks that did not materialise. Meanwhile, "our trench is almost untenable" with even the flies preventing any sleep.

By 20th July, "Mr. Rowan told me that the Turks had received 100,000 reinforcements and that a concerted attack on our position was likely to take place any night. We are making great preparations for defence.. It is expected they will use gas & liquid fire. Pleasant things to look forward to." Next morning, "came out of the trenches very tired, and we were busy all day with one thing or another. As soon as it became dark, I went out with 20 men and erected entanglements in front of our trenches finishing at 3 a.m." The attack did not take place the following day but everyone was so "on the qui vive that we'll all be knocked out for want of sleep.The work in the trenches was most nerve-racking, and greater portion of the night was spent clearing scrub for a good field of fire" - all while Frank was coping with serious dysentery.

By 29th July, "Absolutely nothing doing and am developing beastly liver. Everything gets on my nerves."

By the end of July, Frank was sent to estimate the number of men needed in their new trenches at Russells Top and to "make a sketch of our position, which is an awful one, the stench being awful." "Our new position is a perfect cow, plenty of bombs and dead Turks. We relieved the N(ew) Z(ealanders) in the firing line. 3 casualties." 1st August - "Very weary day in the trenches and we were most thankful to be relieved."

(Frank Anderson's account of his war experiences in 1915 as an Anzac fighting in Gallipoli will continue in Part 3, the next post in this blog.)

Google and an Art Inheritance /

Some while ago, I was fortunate enough to inherit a painting I had always loved in my family home. A coastal scene with a wonderful foreground frieze of golden gorse, it had always delighted me with its luminously expansive feel. I had been told that it was painted from the veranda of my family's home in Albany, Western Australia, but that was all I knew.

One day, I decided to start investigating to see what I could learn about the work. I copied onto paper the almost illegible signature, and eventually started working on Google, trying out whatever I could decipher. Google came up trumps - which, in a way, is less and less of a surprise as time and the reach of Google have taught us all. The signature was of an Australian woman artist, Ellis Rowan,who was active, and prominent, in the late 19th and early 20th century. As I learned a little more about her intriguing, adventurous life, and her skills at self promotion as she developed her career as a "flower painter", I was filled with admiration. I was also delighted to find that she had connections with my redoutable great grandmother, Ethel Clifton Hassell - another very strong character by all accounts. Pushing all sorts of boundaries as a woman, Marian Ellis Rowan seemed to make no concessions in her pursuit of flowers to paint and places that might be of interest.

Ellis Rowan travelled several times to Western Australia, following in the footsteps of her much admired flower painter role model, Marianne North, who travelled the world to paint flower species during the 19th century, finally endowing Kew Gardens with a gallery for her wonderful works. It was thus natural for Ellis Rowan to meet my great grandmother, a community leader in Western Australia and a flower lover. They possibly got on well and I can imagine the scene of Ellis Rowan settling down on the veranda at Hillside, the Hassell home in Albany, to paint the view out to King George Sound. Her skill in painting was considerable, especially given that she often used gouache, which is quick drying and often difficult as a medium. She also used watercolours and oils.

Birds and flowers, of preference tropical, colourful and exotic, were Ellis Rowan's favourite subject matter, and many of her paintings in the National Library in Australia show her skills. She was prolific, and consequently, there is a marvellous diversity in her work. These are but a tiny sample of her flower paintings.

Wild Cornflowers, gouache and watercolour, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Fringed Violet, watercolour and gouache, 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Norfolk Island Hibiscus, watercolour and gouache, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Swamp Banksia, watercolour and gouache, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Black Wattle, gouache and watercolour, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Stumbling on Beauty /

Once in a while, in one of the art newsletters that I receive, I read something that really piques my interest. That happened today in a newsletter that I get periodically from Australia, ArtHIVES. There was an announcement about an artist now living in Brisbane who is short-listed for an art prize in Albany, Western Australia - Nicola Moss.

Looking at her website, and reading her comments about creating some of this beautiful art was rewarding. Not only does she create very sophisticated and compelling paintings, but her observations about the intricacies and fascinations of the natural world in which she works really resonate with me. Her concern for the viability of the natural environment in its tug of war with urban construction seems to underlie a lot of what she does. In her blog, "Layers of Life", she talks too of the time she spends working plein air. All artists seem to deal with the same elations and difficulties when working outdoors, no matter in what country. Nicola clearly has an eye for the small, subtle and elegant as she explores the amazing Australian biodiversity. Nonetheless, her resultant paintings are universal in their appeal.

It is worth going through the links to her website and clicking on the galleries to see her work. Nonetheless, thanks to Nicola Moss, I stumbled on a series of beautiful paintings today.

This Spring and the Next, Nicola Moss artist (Image courtesy of the artist)

I walked along the water's edge – Magic happens here, Nicola Moss artist (Image courtesy of the artist)

Links with the Past /

I am sure that many people feel a sense of wonder and amazement when they realise that they have become serious artists and that it has happened despite there not being any artists in previous generations of their family. That little question, "Where does it come from?", pops into the mind.

This certainly happened to me when I began to get more and more involved in art, long after I had trained in other disciplines and ventures. However, despite the fact that none of my immediate forebears were painters, I was aware of a keen sense of artistry in my mother and her father, both skilled and successful photographers. So I assumed that I had simply chosen another form of expression.

Nonetheless, I found myself excited and gratified when I realised that one of my great-grandfathers had done beautiful renderings of sailing ships, simple and elegant. They seemed gentle messages of encouragement from the past. Then, just before the turn of this year, I discovered with a jolt of delight that I had another art link with the past. My great-great-grandfather, William Carmalt Clifton, was a landscape painter and draughtsman, as well as being the P & O Shipping Company agent in Mauritius and, later, in Albany, Western Australia, from 1861-1870. His last panoramic painting of Albany, done from his yacht in King George Sound, is now in the Western Australian Museum.

Interestingly, we have had in my family various miniatures of him as a young man and a larger oil on canvas painting of William Carmalt Clifton as a 13 year old. The 1832 painting above is a copy of one by Jacob Thompson, a Penrith artist (1806-1879) noted as a landscape and portrait painter who had Lord Lonsdale as his patron.

William Carmalt Clifton, aged 13 years, from painting by Jacob Thompson 1832 (HENRIETTA.RADCLIFFE/1955/ AFTER JACOB THOMPSON 1832)

Miniature of William Carmalt Clifton, now in family collection at Western Australian Museum (Image courtesy of Western Australian Museum)

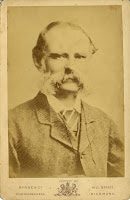

Interestingly, we have had in my family various miniatures of him as a young man and a larger oil on canvas painting of William Carmalt Clifton as a 13 year old. The 1832 painting above is a copy of one by Jacob Thompson, a Penrith artist (1806-1879) noted as a landscape and portrait painter who had Lord Lonsdale as his patron. We also have this photograph of the same Clifton forebear.

William Carmalt Clifton, probably taken after 1872

It is indeed fun to find links - and thus validations - of one's choice of profession and passion that stretch back centuries into the past. Plus ça change, plus ça reste le même, as they say.