Delights of art abound - the trick is being open to their beauty and magic.

Read Moreflower paintings

Google and an Art Inheritance /

Some while ago, I was fortunate enough to inherit a painting I had always loved in my family home. A coastal scene with a wonderful foreground frieze of golden gorse, it had always delighted me with its luminously expansive feel. I had been told that it was painted from the veranda of my family's home in Albany, Western Australia, but that was all I knew.

One day, I decided to start investigating to see what I could learn about the work. I copied onto paper the almost illegible signature, and eventually started working on Google, trying out whatever I could decipher. Google came up trumps - which, in a way, is less and less of a surprise as time and the reach of Google have taught us all. The signature was of an Australian woman artist, Ellis Rowan,who was active, and prominent, in the late 19th and early 20th century. As I learned a little more about her intriguing, adventurous life, and her skills at self promotion as she developed her career as a "flower painter", I was filled with admiration. I was also delighted to find that she had connections with my redoutable great grandmother, Ethel Clifton Hassell - another very strong character by all accounts. Pushing all sorts of boundaries as a woman, Marian Ellis Rowan seemed to make no concessions in her pursuit of flowers to paint and places that might be of interest.

Ellis Rowan travelled several times to Western Australia, following in the footsteps of her much admired flower painter role model, Marianne North, who travelled the world to paint flower species during the 19th century, finally endowing Kew Gardens with a gallery for her wonderful works. It was thus natural for Ellis Rowan to meet my great grandmother, a community leader in Western Australia and a flower lover. They possibly got on well and I can imagine the scene of Ellis Rowan settling down on the veranda at Hillside, the Hassell home in Albany, to paint the view out to King George Sound. Her skill in painting was considerable, especially given that she often used gouache, which is quick drying and often difficult as a medium. She also used watercolours and oils.

Birds and flowers, of preference tropical, colourful and exotic, were Ellis Rowan's favourite subject matter, and many of her paintings in the National Library in Australia show her skills. She was prolific, and consequently, there is a marvellous diversity in her work. These are but a tiny sample of her flower paintings.

Wild Cornflowers, gouache and watercolour, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Fringed Violet, watercolour and gouache, 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Norfolk Island Hibiscus, watercolour and gouache, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Swamp Banksia, watercolour and gouache, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

Black Wattle, gouache and watercolour, c. 1900, Marian Ellis Rowan, (Image courtesy of Museum of Applied Arts & Sciences)

The Siren Calls of Spring /

The stirring of spring, with new growth and blossoms, energises most people. We emerge from shorter days, colder weather and general winter constrictions into the bright, clear light of spring. As days lengthen and the weather grows warmer, everyone starts to think further afield, of more outside activities, more travel, and more plein air art if you are an artist. Endless ideas of where to go to paint come back with insistence, of what to paint or draw, of how to celebrate the world around one.

These siren calls of spring return each year as a renewal of energies for me as an artist. By the end of the winter period, I find myself often flagging, somewhat lacking excitement about subject matter for art. Although the same wonderful flowers and scenes return each spring, they inspire me to draw or paint them, leading to debates about how to depict them in a fresh fashion. Flowers, especially, are my delight. Watercolours and silverpoint both lend themselves to such subjects. The big, bold Azalea indica or Southern Azaleas, for instance, are wonderfully sculptural, their flowers dominating the spring landscapes for a brief and glorious period. I find the subtleties in colour endlessly interesting in the different flowers - Nature is masterful in colour-mixing. It is therefore a huge challenge to be faithful - if one wants to go that route - to these blooms.

Azalea indica George L. Tabor

I realised, years ago, that I owe my mother a big debt of gratitude for any accuracy I may have in colour assessment. As a very young child, barely able to walk, I used to go with her to the brilliantly radiant fields of annual flowers in bloom that we grew for seed on our farm in East Africa. To keep each strain of flower pure and with correct growth, any plant that was of poor quality or with blooms different from the desired type had to be pulled up before it could set seed. I soon became very accurate in detecting variations in flower colour, and I think I retained that eye in later years. I do remember, too, the countless buckets of beautiful, ebullient flowers that we would take back to the house to enjoy because we hated just to pull up a plant and let it die in the hot tropical sun.

It was thus natural, I suppose, that in my art, I return again and again to the sheer joy of flowers when they start blooming in spring. Not only are they lovely in themselves, but to me, they signify much that is wondrous in nature. They offer solace, serenity, hope and energy. No wonder the Japanese celebrate hanami or " blossom viewing" in festivals, of which the most famous are the Cherry Blossom Festivals all over Japan each spring. There is a palpable sense of delight and awe as the Japanese walk beneath these exquisite blossoms and pay tribute to the beauty of nature in all its brief glory.

Cherry Blossom Time in Japan

The same urgent delight and excitement fills me as spring brings its bounty of flowers to the Georgia coast. It is time to start painting!

Flowers in Art /

After a week of much colder weather, the flower garden is definitely in winter mode, save for a few brave camellias now venturing to bloom again. They are one of the most beautiful aspects of Southern gardens for me, and I can never plant enough of them, particularly the whites and pale shell pinks.

Since there is so little variety outside, I have been going through flower paintings in my mind's eye. This was made all the easier as I have been thinking about medieval times, when religious texts were becoming more and more luxurious, with an increasing demand for Books of Hours by wealthy patrons. Many of these jewel-like small creations are bedecked with the most wonderful depictions of flowers, many of them with floral symbols to underline the religious truths of the texts. An introduction to some of these images, with colours glowing and flowers ranging from pinks to violets, asters, forget-me-nots, daisies or roses, shows that by 1410, artists were producing the most amazing Books of Hours for patrons such as Catherine of Cleves, Flemish or French nobility.

Produced in the Netherlands in about 1460, this Book of Hours is from the Euing Collection. University of Glasgow

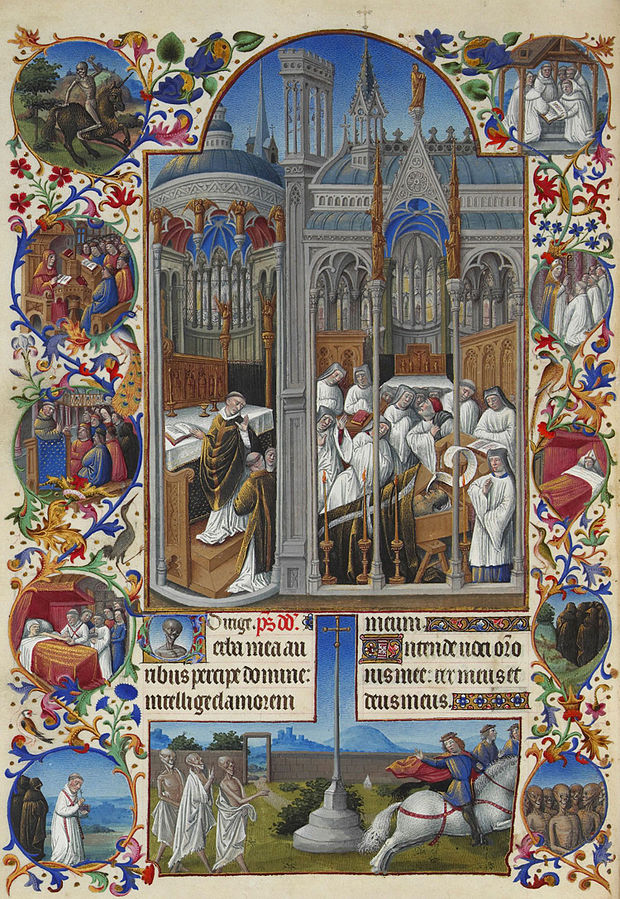

Perhaps the most famous is Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, painted from 1412-1416 almost exclusively by the three Limbourg brothers, Paul, Henri and Jean. Interestingly, there are not many details of flowers, but even here, in one image of a Funeral Service, campanula wander amongst the text on one column.

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry. Folio 86, verso: The Funeral of Raymond Diocrès, between 1411 and 1416 and between 1485 and 1486

By 1500, the use of flowers in Books of Hours was widespread, as can be seen in this edition done in Rouen, France, held in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Palma's Book of Hours, silverpoint and watercolour, Jeannine Cook artist

I created Palma's Book of Hours, done in silverpoint and watercolour, thinking of the tobacco/nicotiana as the flowers opened and closed each day in a rhythm which marked off the hours for me in perfumed regularity.

Another early devotional book, the Wilton Diptych, was created in England c. 1395-1399, for the purposes of accompanying its rich travelling owner. In one scene, pink roses adorn the angels' heads, but apparently they were originally the red Rosa Gallica, one of the earliest known rose varieties.

Richard II presented to the Virgin and Child by his Patron Saint John the Baptist and Saints Edward and Edmund (‘The Wilton Diptych’), Anonymous, ca. 1395, egg on oak, 53 x 37 cm, National Gallery

Detail of the Wilton Diptych

Detail of the Wilton Diptych

An image of this can be found, amongst others, on a wonderful web page on the BBC. This site depicts a wide variety of flower paintings down the ages and it underlines the continuous attraction for artists of flowers, in their beautiful diversity and elegance. This is hardly surprising when one thinks that we humans have always known flowers - they have been in existence for about 120 million years. Fascinatingly, they have apparently always played a central role for humans - archaeologists have found a burial site for a man, two women, and a child, in a cave in Iraq. They were Neanderthals, living in these Pleistocene caves. On this burial site had been placed a bunch of flowers.

The Greeks placed great store on flowers, such as violets and had them in their houses and wore them in crowns at feast times. The Romans did the same and held festivals of flowers to honour the goddess, Flora. Remember the fresco uncovered in Pompeii of Flora and her flowers. Roses were the flower of the goddess of love, Venus; roses too have always been celebrated by Confucians and Buddhists.

The early Renaissance artists loved to depict lilies in Annunciation scenes - Fra Filippo Lippi was one of the early ones in 1450, for instance. Leonardo da Vinci did the most exquisite drawings of Regale lilies. You can almost feel the weight of the flowers as he studied them and drew them in pen and ink. The Pre-Raphaelites also loved lilies - on the BBC site I mentioned earlier, there is a reproduction of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's "Annunciation" with the lilies the most graceful complement. Then there is the wondrously atmospheric John Singer Sargent painting, "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose", done in 1885-6, with the children and beautiful tall, proud lilies in the luminous twilight.

The seventeenth century was also the heyday of Dutch flower painting, done by both men and women. One of the most successful was Rachel Ruysch, while another was Judith Leyster, who did some silverpoint drawings of tulips. Flemish-born Ambrosius Bosschaert was one of the first to specialise in flower paintings and others like Jan van Huysum and Jan Bruegel followed his footsteps with looser, often more brilliant styles. Since a lot of the Dutch flower paintings were also about Holland's wide-flung world power and dominance, as well as the flowers' beauty, the artists did not hesitate to mix up flowers from all parts of the world, which would never bloom at the same time. They composed the most astonishing mixes in their arrangements, requiring a lot of time and ingenuity to pull the complex compositions together.

France forged a different approach to flower painting. Pierre Joseph Redouté began his highly talented life as a flower painter under Queen Marie Antoinette's patronage, but the Empress Josephine hastened to continue the patronage after the Revolution. His wonderfully sensitive "portraits" of flowers and plants are so realistic one can almost smell the perfume, for instance, of his roses, and he managed also to combine careful science with astonishing art. He helped pioneer a whole sub-group of botanical artists whose numbers, today, have swelled amazingly and fruitfully throughout the world. Take a look at the American Society of Botanical Artists' website, for instance - I am proud to be a member of the burgeoning Society. (Dr. Shirley Sherwood, of London, has been one of the major supporters of this renaissance of botanical art, and now her collection is not only showing in many venues around the world, but also at Kew in a permanent, dedicated gallery.)

The second half of the 19th century produced some wonderful flower painters in France - Manet did some exquisite studies of flowers in vases, while Henri Fatin-Latour became famous for the way in which he painted roses and peonies, larkspur and other wonderful summer flowers. He would wait until the roses almost dropped their petals, so as to be able to capture that ultimate fullness of musky beauty in each petal. Monet delighted in his flower garden, culminating with the glories of Giverny and his lily pond, while Renoir and Degas were no slouches in their depictions of chrysanthemums, geraniums and other plants. Of course, everyone knows about Vincent van Gogh and his passionate sunflower paintings – he had moved far from the exquisite jewels of medieval flower painting, but left all of us the richer for both approaches. Odilon Redon comes to mind too for his pastel studies of flowers that were far beyond just the botanical and yet are brilliantly evocative in their somewhat strange feel.

The twentieth century seems to have always had its lovers of flower paintings. An interesting note I saw was that 55% of all art considered "decorative" and available today is floral art. No wonder there was a reaction against flower paintings in juried shows for a long time! Nonetheless, a lot of us artists have continued to celebrate flowers in art - they are just too important to ignore, and besides, when a garden is in the depths of winter, at least one can evoke warmer times by having paintings or drawings of flowers on the walls.