It was a strange feeling. Suddenly, I was asked to become the subject of someone else's art-making. And not just to sit for a portrait in the usual sense of the word. Portraits are usually fairly straightforward affairs, either commissions or records of friends and colleagues. Artists tend to use their fellow artists as subjects because they esteem them, share creative time together (such as Edouard Manet painting Monet working in his studio-boat) or even, sometimes, because they need an inexpensive model. But my request to be the subject was a little different, I learned.

Read MorePhotography

Forms of Still Life /

Inching my way back from the roles of hospital companion and guardian to my husband as he recovered from an emergency operation, I finally felt I could slip back into my artist world a little. It was a welcome move as there is nothing more debilitating, for patient and family, than sojourns in a hospital. My first treat to myself was to see a recently opened small exhibition at the Museu Fundacion Juan March in Palma de Mallorca. Entitled "Things: The Idea of Still life in Photography and Painting", it straddled 17th century Dutch still life paintings and late nineteenth-early twentieth century photographs.

It was a really interesting premise, examining the forms of still life and even the cultural differences in the use of the word, "still life". The German and English versions of the words echo the original Dutch/Flemish concept of examples of things that are faithfully recorded in a carefully organised composition. But the Spanish "naturaleza muerta" or 'bodegon" stray far from the original premise. Most of the work presented represented northern artists, thus closer to the true sense of still life.

The Dutch paintings were lovely small ones, where the artists had delighted in the play of light on a glass goblet or a small ceramic dish, spoon or the crisp glint of a peeled lemon.

The leap to the early medium of photograph to record still life that, mostly, was pre-composed, was interesting. Sometimes, the photographs seemed airless, compared to the paintings, still a characteristic of many photographs today when compared to paintings. Yet there was an elegance and refinement in the photographs that were distinctive. As always, I seem to prefer the very simple compositions - such as one by Baron Adolphe de Meyer taken in 1908 of two hydrangea flowers in a glass of water, the reflections of the glass playing out on the wide expanse of the surface in the lower third of the photogravure.

The selection of photographic still life works was wide-ranging - from daguerreotypes to a coloured autochrome coloured back-lit plate of flowers by the Lumiere Brothers done in 1908, a circa 1895 trichromatic print of flowers (so much for all our modern "inventions" of technicolour) and then into the more modernist 1920-60 black and white work by Man Ray, Walker Evans, and many other European photographers.

Every interpretation of still life was there one could imagine - from carefully set up compositions, to views of life made still in abattoirs or after a volcanic eruption to Walker Evans spotting a natural still life scene on a back porch of a (sharecropper?) weather-beaten clapboard house.

As I looked at the different compositions and the elements that made up those compositions, mainly derived from nature, I could not help realising that most of my current artwork is, de facto, still life. I am using elements of nature in compositions that record stones, bark, flowers --stilled by being placed in a setting other than their original one. I have only strayed a little, like many other artists, from the path of still life "inventor" artists of the seventeenth century by cropping, zooming in on some elements and eliminating others, framing and thus altering the original concept and layout of the still life set up.

I love feeling this sense of kinship and heritage that comes when you look at artwork from previous times and understand how and why you do things the way you do, thanks to those earlier artists.

Colour versus Black and White /

When you are surrounded by brilliant, sunlit hues and above the sky is blindingly blue, it is easy to be captivated by colour and want to translate it into your art. We all resonate to colour, and it is and always has been the dominant approach to painting. Nonetheless there are those, artists and art lovers, who also resonate to black and white and shades of monochrome in between.

I read of a perfect summation of this difference in an El Pais article about the resurrection of the Leica camera, once considered the ne plus ultra of 35 mm. cameras for most of the 20th century. Every great photographer, from Capra to Henri Cartien-Bresson used a Leica because it was quiet, highly portable and had remarkable lenses that allowed fantastic photographs to be taken. Cartier-Bresson believed too that all edits to the image should be made when the photo was being taken, not afterwards in the darkroom.

Until the digital camera came along, Leicas were much esteemed. When the then nearly bankrupt company was bought out in 2005 by Andreas Kaufmann, heir to an Austrian paper company fortune, a fascinating development occurred. Andreas Kaufmann gambled on differentiating Leicas from all other digital cameras: the M Monochrom Leica only takes black and white images. When this Leica was launched in May 2012, the model was priced at a cool 6,800 euros. It has become a runaway success in the photographic world, selling like hot cakes through Leica Boutiques around the globe.

As Andreas Kaufman was quoted as saying, “For me, colour is more emotion, while black and white represents structure.” The remark resonated with me.

True, I was brought up with a grandfather and mother both photographing in black and white in East Africa. In fact, they were so successful that they kept the farm going on photographic sales during the dreadful Great Depression years when the farm was in its infancy and barely sustained them as a family. I have always considered black and white photographs of the 1930-50 era in Europe as marvellous works of art, as well as the amazing photographs that Edward Weston and Ansel Adams took in the earlier 20th century.

I also love black and white drawings for their immediacy and unadorned truth of execution. Look at this one for direct simplicity and power of composition.

Even black and white paintings have an impact that indeed speaks of structure and logical thought.

It is as if you can get your teeth into a black and white work of art, while one in colour is a fraction fuzzy, tugging at emotion and heart strings. Portraits, landscapes, even still life or abstracts: they all evoke passion, sympathy, joy, sorrow, lyricism. Black and white images seem more cerebral, more challenging often. I find it logical that I am more and more fascinated by metalpoint drawing – it is all back to black and white.

Plus ça change, plus ça reste la même!

After the Invention of Photography /

Down the ages, man has historically turned to the surrounding world to create a virtual reality in art, through the complex interplay of what the eyes perceive, how the colours have impact and what emotions are invoked. In other words, artists have used the world around them as the major source of their artistic inspiration and subject matter.

After the invention of photography in the decades before 1850, the basis for art making changed. As Henri Matisse observed, "The invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature," which enabled the artist "to present emotion as directly as possible and by the simplest means."

La Danse (I), Henri Matisse, 1909. Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Indeed, after the mid-19th century, artists' experiments grew more and more divorced from nature in many instances. Monet, for instance, still based his work on nature but it was often a very different vision and interpretation of nature, which meant, of course, that he was regarded as a main innovator in the new school of Impressionism.

Impression, soleil levant, 1872, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris

Water Lilies, 1920, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London

As the years passed and artists grew less and less interested in the old, academic way of depicting the world around them, experiments multiplied. Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cezanne, then Picasso, amongst others, led the way to an art that put more emphasis on colour, emotion and thus a psychological impact. Cezanne compressed, distorted, changed perspective, volumes, relationships, colour relationships and played such games with "reality" than he was viewing in his surrounding world that we are still indebted to him in terms of interpretation of subject matter. He stared and stared at his subject matter, but then he in essence produced metaphors about the nature he was looking at; he was "a total sensualist. His art is all about sensations", said Philip Conisbee, curator at The National Gallery, who put together an exhibition of Cezanne's work in 2006.

Le Pont Des Trois-sautets, watercolor and pencil, Paul Cézanne, c. 1906, Cincinnati Art Museum

Beyond Cezanne, of course, the art world turns to Cubism, abstraction and any number of other forms of presenting emotion directly andurgently, leaving behind any remote reference to a virtual reality of the world. Photography's invention as a "liberation from reality" indeed, for a time, ensured that artists used a very different language to convey aspects of their world. Georges Braque was one such artist.

Violin and Candlestick, Georges Braque, Paris, spring 1920, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

After Piet Mondrian's early experiments with Cubism, his path led to works that have become iconic.

Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow, 1937-42, Piet Mondrian, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London

As the 20th century advanced, artists strayed further and further away from their surrounding reality, totally divorced from it by photography's invention - whether the artists were conscious of this fact or not. But then, of course, the pendulum began to swing back the other way as perhaps, artists began to run out of ways to express themselves that were truly new and different abstractions. So photography comes back into play, manipulated and used in new and sophisticated ways to depict realities. Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Audrey Flack and many others, especially in the United States, have worked in amazing ways that also built on Edward Hopper's reclusive reality that had been a more lonely stream of 20th century art in America..

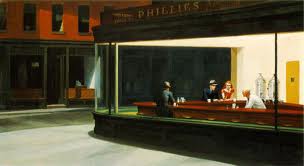

Night Hawks, Edward Hopper, 1942, oil on canvas (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Richard Estes “Columbus Circle Looking North,” 2009 Oil on canvas, 40 inches by 56 1/4 inches. Linden and Michelle Nelson Tenants by the Entirety © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

And so the circle is closed and artists once more have recognised the potential of photography in making art. Indeed there are many artists who predicate their depiction of the world around them on photographs, even, in some cases, to tracing images onto canvas. Nonetheless, even their interpretations of reality have been influenced by the long deviations in art-making, away from the need to copy reality. We are all heir to what has gone before us.

Lessons from photographer Edward S. Curtis /

I have been reading the recently-published, fascinating biography, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: the Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis, by Timothy Egan. There is much to think about, particularly about Curtis' lifework recording the vestiges of the American Indians' lives, but also about his approach to photography and art.

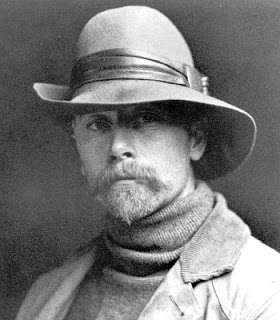

Edward S. Curtis, Self-Portrait, 1889

Curtis started out with a very limited education, but that did not prevent him becoming an outstanding and very famous photographer by the turn of the 20th century.

Princess Angeline (Kikisoblu), ca. 1895, Photo by Edward S. Curtis, Courtesy UW Special Collections

This amazing photograph was one of the first that Curtis took of an American Indian, the last surviving daughter of Chief Seattle, who lived in a waterfront shack in Seattle, the desperate remnant of a once-proud tribe.

According to Tim Egan, Curtis devoted great energies, first to studying pictures of the great art of the world - portraits, landscapes, all forms of painting - and then to translating his insights to the medium of photography. His understanding of light, context, simplicity of composition, intensity of approach show an artistry that became one of his hallmarks throughout his life in photography.

A Smoky Day at the Sugar Bowl – Hupa, 1923, .Photograph by Edward Curtis, Credit: Library of Congress

The other lesson that is clear from Curtis' work is that he created so many wonderful images because he knew his subjects well. Whether it was Mount Rainier, the Hopi Indians, the Navajo or any other Indian tribe he recorded, he made it his business to find out as much as possible about the subject. He knew what aspects to emphasise, what was important to record, how to bring out the beauty, the essence or the historical, human or physical significance of the subject.

In other words, he followed the wisdom of all successful artists, in all media - know your subject so that you can depict it in the best and most meaningful way.

Art and Photography /

Recently, I seem to have been seeing more and more allusions to artists who make or have made considered efforts to make art that in some way fights back against the all-pervasive influence of photography.

Turner was one of the first artists to do this, at a time when photography was newly invented. (The Frenchman, Niepce, made the first permanent photograph in 1826.)

Joseph Nicephore Niepce

By 1819, Turner had already begun to move away from paintings that were faithful reproductions of the world around him after a visit to Venice.

Ivy Bridge, Devonshire, c.1813-1814, J.M.W. Turner (Image courtesy of the Tate.org.uk)

He continued, however, to make careful studies of clouds, of storms and waves, for instance, which were the underpinnings of many of his paintings. His interest was far more directed towards capturing his vision of things, rather than reproducing the exact likeness of the world around him. It was thus a way of rebutting the influence of photography's slavish capturing of appearances.

Sunrise, with a Boat between Headlands, 1835, J.M.W. Turner (Image courtesy of the Tate.org.uk)

Ever since the invention of photography, there has been this tug of war between "fine art" and photographs, a contest that de facto seems to be have won in large part by photography. One ironic measure of this in our parlous economic times is the number of photography exhibitions in museums which has greatly increased in recent years. One suspects that costs of mounting and insuring such exhibitions might be a consideration. The prices of photographs is also climbing steadily for many historic works as well as contemporary prints.

Photographs have also become the drawing book of preference for many artists, as opposed to actually drawing scenes or objects that will be later incorporated into a work of art. Many artists go as far as simply reproducing the contents of a photograph, ideally one that they have taken themselves as opposed to using someone else's and thus infringing on copyright. There is always a danger in using a photo for art - if the artist is not already very familiar with the object or scene, having drawn or painted it before many a time, a photograph can be a fickle friend. The camera lens cannot "see" all that the human an eye can see, so a great deal of information is missing that might help in creating a work of art. Added to that, a work of art based too heavily on a photograph tends to have a frozen look, airless and static. Somehow, the image has not been processed through the artist's eyes-brain-hand in the same way as it would have been if drawn or painted from life.

Every artist today has to decide just what role photos should play in the production of his or her art. Whether the art is realistic, abstract or in between, photography can be a useful tool or a demanding taskmaster. Each of us has a interesting choice to make.

A Sense of the Marvellous /

I saw a large and diverse exhibition of black and white photographs of Paris, Twilight Visions: Surrealism, Photography and Paris, at Savannah's Telfair Museum. In the introductory explanation about all these photos which mostly date from the 1920s and 1930s, there was the phrase, "a sense of the marvellous". It struck me, because it is so important to retain that sense, especially if one wants to be an artist.

The exhibition did indeed illustrate some wonderful moments. Serendipitous sights - the wonderful reflection of buildings in a puddle by the pavement's edges by Ilse Bing, for instance, or extraordinary patterns of shadows and people beneath the Eiffel Tower by Andre Kertesz - were accompanied by more planned photographs of the illuminated Eiffel Tower. or old street scenes in Paris. There were many photographs which were much more "contrived", in keeping with the prevailing surrealism movement. But it was the photographs that record the photographer's eye and awareness of magic and marvels that I savoured most.

Ilse Bing, 'Three men on steps by the Seine' , (Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum)

Ilse Bing, Rue de Valois, Paris, 1932, gelatin-silver print, (Image courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Perhaps I am greatly influenced by all the childhood hours I spent with my photographer grandfather, Frank Anderson, as he photographed herds of giraffe or other wild animals on our farm in Tanzania. With an important body of work to his credit, as he documented the disappearing tribes and the East African wild life, Frank had a keenly developed sense of the marvellous. He taught me that observation and awareness, as well as quick reactions in capturing a photograph, are key. Key to art-making, but key, too, to a deep enjoyment and appreciation of life. It was an invaluable preparation for my later life as an artist.

Children in central Tanganyika, 1929-30, sepia print, Frank Anderson photographer (copyright Jeannine Cook)