There is a really fascinating exhibition currently on display at the National Gallery in London:Painters' Paintings: from Freud to Van Dyck. The seed for this show was apparently the donation to the National Gallery of Lucien Freud's Italian Woman by way of the Acceptance-in-Lieu programme after Freud's death. Its arrival prompted the Gallery to investigate how many artworks in its possession had belonged to artists down the ages. The result of this inventory is this wonderful, interesting exhibition.

Read MoreMatisse

After the Invention of Photography /

Down the ages, man has historically turned to the surrounding world to create a virtual reality in art, through the complex interplay of what the eyes perceive, how the colours have impact and what emotions are invoked. In other words, artists have used the world around them as the major source of their artistic inspiration and subject matter.

After the invention of photography in the decades before 1850, the basis for art making changed. As Henri Matisse observed, "The invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature," which enabled the artist "to present emotion as directly as possible and by the simplest means."

La Danse (I), Henri Matisse, 1909. Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Indeed, after the mid-19th century, artists' experiments grew more and more divorced from nature in many instances. Monet, for instance, still based his work on nature but it was often a very different vision and interpretation of nature, which meant, of course, that he was regarded as a main innovator in the new school of Impressionism.

Impression, soleil levant, 1872, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris

Water Lilies, 1920, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London

As the years passed and artists grew less and less interested in the old, academic way of depicting the world around them, experiments multiplied. Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cezanne, then Picasso, amongst others, led the way to an art that put more emphasis on colour, emotion and thus a psychological impact. Cezanne compressed, distorted, changed perspective, volumes, relationships, colour relationships and played such games with "reality" than he was viewing in his surrounding world that we are still indebted to him in terms of interpretation of subject matter. He stared and stared at his subject matter, but then he in essence produced metaphors about the nature he was looking at; he was "a total sensualist. His art is all about sensations", said Philip Conisbee, curator at The National Gallery, who put together an exhibition of Cezanne's work in 2006.

Le Pont Des Trois-sautets, watercolor and pencil, Paul Cézanne, c. 1906, Cincinnati Art Museum

Beyond Cezanne, of course, the art world turns to Cubism, abstraction and any number of other forms of presenting emotion directly andurgently, leaving behind any remote reference to a virtual reality of the world. Photography's invention as a "liberation from reality" indeed, for a time, ensured that artists used a very different language to convey aspects of their world. Georges Braque was one such artist.

Violin and Candlestick, Georges Braque, Paris, spring 1920, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

After Piet Mondrian's early experiments with Cubism, his path led to works that have become iconic.

Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow, 1937-42, Piet Mondrian, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London

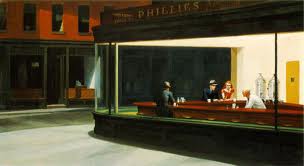

As the 20th century advanced, artists strayed further and further away from their surrounding reality, totally divorced from it by photography's invention - whether the artists were conscious of this fact or not. But then, of course, the pendulum began to swing back the other way as perhaps, artists began to run out of ways to express themselves that were truly new and different abstractions. So photography comes back into play, manipulated and used in new and sophisticated ways to depict realities. Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Audrey Flack and many others, especially in the United States, have worked in amazing ways that also built on Edward Hopper's reclusive reality that had been a more lonely stream of 20th century art in America..

Night Hawks, Edward Hopper, 1942, oil on canvas (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Richard Estes “Columbus Circle Looking North,” 2009 Oil on canvas, 40 inches by 56 1/4 inches. Linden and Michelle Nelson Tenants by the Entirety © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

And so the circle is closed and artists once more have recognised the potential of photography in making art. Indeed there are many artists who predicate their depiction of the world around them on photographs, even, in some cases, to tracing images onto canvas. Nonetheless, even their interpretations of reality have been influenced by the long deviations in art-making, away from the need to copy reality. We are all heir to what has gone before us.

Attitudes about Flower Painting /

I have always been interested to listen to the "intonations" with which people speak or write about flower paintings. Floral art has often had a difficult time ascending high on the ladder of art appreciation, in circles of art officialdom.

Despite flower painting having illustrious beginnings from the 16th century onwards, with Northern Renaissance Dutch and Flemish artists, flower painting has historically been associated with amateur lady painters who pursued art as a pleasant, genteel past time. Very few male artists have painted flowers as their main subjects - Manet, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh and other 19th century artists did some wonderful paintings of flowers, very much as still life. This painting done in 1883 by Edouard Manet is a perfect example.

Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase, Edouard Manet, 1882, (image courtesy of the Musee d'Orsay).

Henri Fatin-Latourwas one of the most amazingly passionate painter of flowers, again as still life. These artists did however observe the flowers carefully and closely, and knew how these plants grew.

H. Fatin-Latour, White Roses, 1875, (Image courtesy of York Art Gallery, York, UK)

Other later male artists, from Picasso to Matisse and beyond, occasionally painted or drew flowers, but often, the results were more generic.

Matisse, Flowers, 1945

Meanwhile, women artists were creating beautiful "portraits" of plants and flowers, many using the botanical approach as their springboard.

Ellis Rowan was travelling through Australia and South East Asia in her quest to paint brilliant and exotic flora. Perhaps the conscious or unconscious links between gardening and flower paintings in British circles helped foster the interest in such art in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa as well as Great Britain.

Carolina Jessamine, Gelsemium sempervirens, Ellis Rowan

Another wonderful result of celebrating a garden was the art Childe Hassam created in Celia Thaxter's garden on the Isle of Shoals, Maine. This is one such painting Hassam did in 1890, now in the Metropolitan Museum.

Celia Thaxter's Garden, Childe Hassam, 1890, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Despite all these - and many, many other - instances of superb floral paintings, I cannot help being aware of a certain tone when such art is talked to in today's art world. Almost a sneer, not quite? As if paintings about flowers are, really, not quite "up to snuff". Despite a huge renaissance of botanical art (mostly done, need I say, by women artists), despite the trail blazed so memorably by Georgia O'Keeffe with her sensual, strong interpretations of flowers, there is still a je ne sais quoi in the air on the subject of floral art.

G. O'Keeffe, Two Calla Lilies,1928 (Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

This attitude fascinates me because, as I struggle to draw or paint flowers, I realise, repeatedly, that tackling flowers as a subject is very complex. In fact, just as challenging a subject as nudes, landscapes or anything else that are considered more "serious". By the time that an artist has mastered the intricacies of plants, their flowers and leaves, he or she is pretty capable of tackling any other type of art subject imaginable, and in any medium..

Maybe the decades when drawing was considered unnecessary contributed to the dismissal of flower-based art. Perhaps today's emphasis on conceptual art also is a factor, with the overtones of floral paintings lacking "gravitas" and deeper meanings. It is however ironic that part of the art world is so dismissive of floral painting, because another, large part of the art-loving world is very happy to embrace it.

Just as well, I conclude. Think what complexities and delights artists would miss if they never looked closely at a flower!.

Playing /

I listened with fascination this morning on National Public Radio to a programme, Play, Spirit and Character, on Krista Tippett's show, Speaking of Faith, which talked of playing and its importance in life. Stuart Brown was being interviewed. His wisdom and insights on how animals and humans need to play, in infancy, childhood and adulthood, were fascinating. It is well worth seeking out the interview on the Web.

As Stuart Brown talked about playing, I realised how important playing has always been as I tried to create art. Every time that I want to experiment, to push out boundaries, to improve as an artist, I have always regarded the experience as play. I had not measured, apparently, the vital role play has in daily life, let alone in art. Licence to do something different, unusual, amusing, distracting, lively - these are all versions one can find in the Oxford English Dictionary as definitions, amongst many, of play. Freedom too is a definition. In other words, play is an integral part of one's creativity as an artist: without it, one is liable to be stultified, stuck and dull. Oh!

Think of Manet, Monet, Cezanne, the Fauves, Matisee or Picasso, amongst so many artists - they all show a sense of play in their work, and those works usually herald changes and break-throughs in their development. To say nothing of the spirit of play that one sees among many of the most successful artists of the 20th century, many of whom definitely do not or did not take themselves or the world around them too seriously. It was good to have it reaffirmed in the radio programme today that one needs to play, every day, in all the realms of one's life, but especially in art.

Fishing Boats, Collioure, 1905 , by Andre Derain

Perfumes, sound and light /

I have just spent time in my other home in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. There, it is a green and beautiful spring after bountiful rains this year, and the island is celebrating with exuberant growth on mountain slopes and down stony valleys.

I had some time to paint and draw, and once again, my sense of place was expanded and extended. I know that wherever one is working outdoors as an artist, you become conscious of all your surroundings. It seemed to be especially the case this spring in Spain: the perfume of orange blossom, lemon blossom, jasmine and roses floated everywhere on the air.

Citrus sinensis Osbeck painting by Mary E. Eaton from a 1917 issue of National Geographic

As the sun warmed, each morning, and the sky became brilliant, the perfumes intensified and became intoxicating. The light grew more brilliant - oh, that Mediterranean light! And as I sat quietly, totally enraptured with all this light and drunk on these exquisite perfumes, I was serenaded by blackbirds singing their wondrous melodies, or tiny serins buzzing excitedly high in the trees above.

I was soothed and inspired. As the light changed and the flowers I was depicting opened, moved and faded, I was enveloped in this world in which I was sitting. I felt a bond and a sense of kinship with all the wonderful artists who have worked in the Mediterranean region down the ages - Italian masters like Botticelli or Guercino, Corot, Monet, Renoir, Matisse, Cezanne or Raoul Dufy in France, even Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida, just to name one Spanish artist who celebrated so superbly the brilliant light of Spain (go to this site if you speak Spanish or this one for English). They all responded to the same light, perfumes and sounds. From the flowers painted on the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs to the frescoes on walls of opulent homes in Pompeii, artists have always gloried in the beauties of flowers growing in the Mediterranean world. I felt it was a great privilege to be immersed in this world of brilliant light, intoxicating perfume and liquid bird song, as I celebrated Mallorca's spring flowers in silverpoint and watercolour.