It was a strange feeling. Suddenly, I was asked to become the subject of someone else's art-making. And not just to sit for a portrait in the usual sense of the word. Portraits are usually fairly straightforward affairs, either commissions or records of friends and colleagues. Artists tend to use their fellow artists as subjects because they esteem them, share creative time together (such as Edouard Manet painting Monet working in his studio-boat) or even, sometimes, because they need an inexpensive model. But my request to be the subject was a little different, I learned.

Read MorePortugal

When Artistic Seeds Germinate /

Last year, I felt I was seriously in need of being shaken around as an artist, as I was too often wont to work in my comfort zone. I was experimenting every time I could, but there were not many occasions to work as an artist as other events were impinging too hard on my life. Nonetheless, the experiments were not all that daring, I felt.

This was one line of work - a mixture of realism and stylised silhouettes in Mylar. Another line of subject matter I was exploring was my on-going series on tree barks.

Another series was totally abstract, seemingly, but in reality, based on the extraordinary designs that Neolithic man had already devised for his pottery.

Nevertheless, I felt that I needed to free up, something that is quite hard to do with metalpoint drawing, as there is a terrific feel of friction, well almost friction, when one has the stylus making marks on the drawing surface. I wondered whether I needed to work much bigger, but also felt that for that purpose, metalpoint would be a very big challenge. So I decided that at my residency last summer at Draw International, in France, I would take lots of other drawing media and see what came of it all.

I soon realised that I needed to free up from more than just drawing inhibitions. I had to work through an enormous amount of stress from family illness with which I had been coping, even to getting enough sleep. Then I found that I was indeed being pushed out of any comfort zone, utterly. Of course, the resultant work was all over the place, but mostly I was using graphite, a much more forgiving medium and one that allowed for all sorts of smudged and gestural effects, the antithesis of metalpoint effects.

I struggled on, feeling at sea, conscious that I needed to feel at sea, but of course, that is never a happy place to be as an artist! I just had to listen to the small inner voice, that old friend, and be counselled that sooner or later, things would begin to work out and I would find my voice, albeit, I hoped, a slightly different and better one. Part of the trouble was, of course, that I have continued to have very little time to devote to art and to bury myself in it.

However, I had the luck to go off for the two blissful weeks to the artist residency I was given at OBRAS Portugal this early spring. There, suddenly, things began to feel more comfortable. Yes, I am still doing realistic things, but not always in the predictable realistic way of yore. I feel more comfortable in daring and venturing into much more unpredictable ways of working. In short, I am finding new voices, slowly slowly. The seeds that were rather painfully planted last year in my garden of art are slowly beginning to germinate. That is exciting.

Boulders, Works of Art or Something More Important? /

Reading an article by Stephen Knudsen in April-May’s edition of Professional Magazine entitled ”To see a Work of Art” made me think back to a recent experience I had in Portugal. Knudsen’s article was about spending a day at the Los Angeles Museum of Art to see sculptor Michael Heizer’s LevitatedMass.

Steve Knudsen first explained about the controversy surrounding the granite boulder’s final installation at the Museum in 2012 after Heizer first sketched out the idea back in 1969.Then Knudsen described the rewards of sitting watching this enormous boulder suspended over a ramp, ranging from the reactions of fellow visitors of all ages to the final crescendo at sunset of the boulder seeming to rise as the sun sank. He comments that “the seemingly grand narrative of moving the rock was, in the end, just a blip in the bigger story that points to sublime space, celestial movement and geologic time” (my thanks to him for this quote).

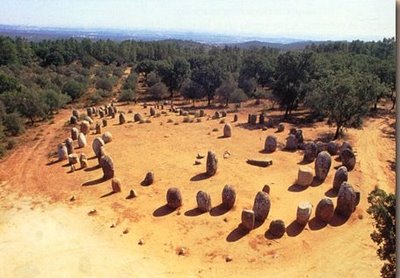

His remarks took me straight back to my amazing hours in early March at the Cromlech dos Almendres, near Evora in Portugal. One of the most important megalithic complexes in Europe, it is sited on a gentle hillside, overlooking rolling hills towards Evora, amidst olives and cork oaks. Daring from the 6th millenium BC, this extraordinarily grandiose ensemble of roughly one hundred boulders takes one's breath away as you approach the wide-flung site.

Just as Michael Heizer must have thought long and hard about his boulder, its shape, its material, its potential home and how it would best be viewed there, its messages and meaning to anyone viewing it – even how to transport it to the site, so too, our ancestors must have spent much time planning the Cromlech dos Almendres.

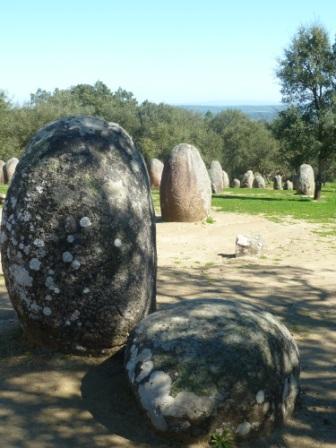

Like Heizer’s boulder, the huge megalith boulders are granite. Wonderful shapes, some of these monoliths have some carving on them, now well worn, but still hugely evocative as the sun moves and catches different angles and shapes on their surfaces.

Apparently these boulders were placed at different times, in concentric circles and later ellipses, all on a southeast-northwest axis. The entire group occupies an area of about 70 by 40 meters. Many of these massive stones are three meters high, while others, of earlier date, are slightly smaller.

Just to transport them to this hillside must have required incredible effort and organization, let along to site them and erect them into a vertical position. The endeavour speaks of enormous religious and social fervor, amongst groups of people who were few in number to start with. Connections with the land, their gods perhaps, their social structures – this was a huge undertaking to assemble these wonderfully powerful and eloquent boulders. Perhaps too the ensemble of monoliths was used for astronomical purposes.

Whether artistic considerations came into their choices of the stones to transport and place – who knows. But the carvings, whatever their significance, are beautiful too, and the carvers must have been conscious of that aspect. Many of the stones are flatter on one face, perhaps shaped deliberately. Each boulder speaks, as the sun moves around it and it relates to the next boulder and then the one beyond. The tactile qualities of the granite, so enduring, so interesting as the lichens hint at the northern side of the boulder, are memorable.

Like Stephen Knudsen’s perceptions of Levitated Mass at LACMA, the impressions that the Cromlech dos Almendres leave with one are of grandiose endeavours. Eight thousand years ago, men and women believed deeply enough in matters beyond their daily needs, in matters that transcended space, time and the span of human life, to expend enormous physical effort to create a sacred place of power and great beauty, sited exquisitely, laid out with care and sensitivity for the natural flow of life.

Even in our complex technology-driven 21st century, a visitor to the Cromlech is awed and inspired by the powerful voices that speak to us from the past of older, deeper, more important matters.

Marble - the Glory of Estremoz /

One of the attractions of my going to OBRAS Portugal for an artist residency was the marble that is found in the Estremoz area.

I had already seen examples of this lovely, varied but subtle white marble on previous visits to the Alentejo, but it seemed to me that its character lent itself beautifully to silverpoint drawing.

The marble is found in a wide swath in the Alentejo, 27 km by 48 km, running NW-SE, with a depth of nearly 400 metres, but Estremoz is near the centre of the area.Historically this marble has been mined since 370 BC, as was discovered by a tombstone, and the Romans used it for many building projects. The Roman temple in Evora has bases and capitals of marble, while the Roman theatre in Merida, Spain, also has Estremoz marble.

It was soon being widely exported around the Mediterranean and by the Middle Ages, this marble was incorporated in major religious and secular building projects throughout Portugal. By the 15th century, Estremoz marble found its ways to Africa, Brazil and India, in all parts of the Portuguese Empire. The list of important European buildings adorned with this marble ranges from the Jeronimos Monastery in Portugal, to the Escorial Monastery in Spain, to the Louvre, Versailles and the Vatican. Now, the marble is exported worldwide, and Portugal is one of the major producers of marble in the world.

In Estremoz itself and the surrounding areas, marble is an integral, elegant part of all aspects of building. Door and window frames, lintels, floors, stairs, pavements walls – there are touches of marble everywhere, and the cemeteries are a celebration of this stone. Of course, sculptors celebrate this marble as well and there are many artists currently working in it in the Estremoz area. One such sculptor whose work I acquired is Pedro Fazenda. Its colours are mainly white, some with veins and then there are subtle rose shades that can be beautifully translucent, some veined, some less so.

The mines themselves are deep and vertiginous – huge blocks carved out, down and down. Some of the mines have been abandoned as water sources were struck and the quarries filled with water.

Others are still a forest of cranes and heavy equipment disappears down to tinker-toy size far below the surface. Vast mountains of tumbled blocks of waste marble rise drunkenly to the sky in olive groves, and there are piles of sawn-off pieces of marble that beg to be touched and taken. Cores of marble samples lie in abandoned factory areas, while other leased-out mines hum with activity.

There is always the question of how to use the waste marble – one vast pile outside Estremoz was apparently destined to be ground into the chips for the bed of the AVE high speed train link between Madrid and Lisbon. Alas, EU funding dried up for that project and the giant blocks remain intact today.

Needless to say, I could not resist the blocks of marble and am still exulting in its quiet beauty. These are some of the drawings I have done so far – with more silverpoints still to come…

Portuguese Memories - Gleaming Tiles /

After a marvellously creative and stimulating time at an OBRAS art residency in Evoramonte, Portugal, I have been remembering back to vignettes of great beauty.

One of the wonderful delights, of course, was seeing the diversity of the tiles or azulejos about which I have written previously. Since I was spending time in the fortress hill town of Estremoz, in the Alentejo region, I was charmed by some of the modern versions of tiles, adorning the facades of houses in the centre of town.

More historic tiles in Estremoz include amazing tile pictures all around the outside of the original train station, serving a railway line built for the Kings of Portugal to travel between their various palaces.The railway line is long disused and a tangle of brambles and flowers, but the railway station in Estremoz is protected, with the tiles covered by Plexiglas against vandalism or theft.

More delicious houses shouldered together around the main, vast Estremoz square, some of which told of their builders' dreams and aspirations.

Much earlier azulejos adorn the handsome stairs up the main building of the present municipal offices, once part of the “Congregados” convent and church that was started in 1698. I was fascinated by the hunting, fishing, boating and picnicking scenes, and thought the top “ladies” were fun.

Everywhere you go in Portuguese towns and cities, there are details of interest or delight that stop one in one’s tracks. The azulejos, modern and of previous centuries, never fail to add colour, harmony and life to buildings.

Azulejos - Those Amazing Portuguese Tiles /

Every time I return to Portugal, I find I fall in love all over again with the azulejos, the glazed tiles that are the quintessence of Portuguese wall coverings, on the outside of buildings, inside churches, monasteries, even private houses, everywhere.

The beginnings of this wonderful art form date from over five centuries ago, when the Moors held sway in the Iberian Peninsula.In fact, the word azulejos comes from the Arabic word for “polished stone”, zillege,and the early types of tile - floral, geometrical, curvilinear in patterns - were introduced by them.Soon the Mozarabic centre of tile making was Seville, and for a time, Portugal imported tiles after King Manuel I visited the Seville factory in 1503.The Spanish adopted the Arab love of filling space and patterning everything.

Early 16thcentury Seville tiles,Evora Museum, Evora

Later in the 16th century, the Portuguese learned how to make the tiles themselves after they had captured Ceuta in 1415, and after an influx of Flemish, Spanish and Italians brought their pottery skills to Portugal. (Their arrival is a reminder of how skilled workers flow around the world to where there is wealth and thus work; it is not just a phenomenon of our times!) The heyday of azulejos began and soon churches were adorned in amazing friezes and vast picture panels in “Delft blue”, palaces were tiled from top to bottom, stairways became glowing glories, the facades of buildings were works of art beyond belief. Wherever one goes in Portugal, there is beauty and complexity, thanks to the azulejos.

Just a few examples of tiled interiors that I have delighted in recently, in Evora and in a lovely small restored 16th century church in Redondo, both in the Alentejo region, inland and east of Lisbon.

If you are in Lisbon, one of the most fascinating and delightful museums to visit is the National Azulejos Museum. Spend all day there if you can – you will be rewarded. And elsewhere in Portugal, don’t forget to slip into every church or historic building you see, because there will be great beauty to reward you, thanks to the azulejos.

The Excitement of Drawing /

I have always admired Paula Rego's capacity to draw really well and also to skewer people in the political art she does so effectively. I was really thrilled when I was accepted into the New Hall Women's Art Collection at Murray Edwards College, Cambridge, (www-art.newhall.cam.ac.uk/gallery/artists) because they have some of Rego's work. Now Paula Rego is having a new museum dedicated to her in Cascais, Portugal, her home country, and she is ever more enthusiastic about drawing. In a recent interview with Andrew Lambirth in The Spectator (http://www.spectator.co.uk/), she talked about the process of creation through just getting on and doing the drawing, mindful of the changes which will probably take place. She explained, ..."when you discover what things look like from drawing them, it's most exciting. You forget everything else because your attention is totally focused on what you are doing ..."

Drawing is indeed a most exciting adventure every time you pick up a drawing instrument. You learn how things are put together and how they work, in space, in differing lights, in time. You have no idea what really will happen on the paper until you have completed the drawing (or, more accurately, when it tells you that you have finished...). The initial concept or inspiration that impelled one to launch on the drawing in the first place is never the whole story. As you look hard, at length and with increased understanding, at what you are drawing, you - the artist - are changing too. Your imagination is being stimulated and all sorts of new connections and thoughts occur. Every time one does even the briefest of drawings, life is enriched.

Pomagne, Paula Rego., 1996 (Image courtesy of the Tate)

No wonder Paula Rego talks of losing track of time when she is drawing. All acts of creation are miraculous erasers of the sense of time! Just ask the patient companion of any artist who has been assured that "this will just take five minutes to do..." as the artist tries to do a quick drawing or painting; half an hour later, or more, the companion is still probably waiting, less patiently! Being totally focused on drawing or painting is incredibly meditative and often healing too. Frequently I find that my sense of "the world being in balance" is directly related to how much I am painting or drawing. It has little to do with the degree of success of the art you are doing - it is the act of creation that counts. It is back to that excitement of drawing - the next voyage of discovery.