Light footsteps flying down the spacious stairway, sunlight flooding through the big windows, laughter and a welcome soon sealed with a glass of wine: my stay at Hotel Sainte Valière began deliciously.

Hôtel Sainte Valière, Sainte Valière, France

I soon learned that this gracious house, one of the main homes built in this small hilltop village during the 19th century wealthy heyday of wine culture in the Languedoc Roussillon area of southern France, was originally called a “winegrower’s folly”. The Cayla family knew how to make a home of gracious proportions, and today’s guests at Eloise Caleo’s Artist Residency are the lucky beneficiaries. The family lives on the top floor, with wonderful views out over the Minervois area and the green, bountiful vineyards, and on the middle floor are three spacious rooms and private bathrooms for the residents. Meals, if you chose to take them with the family, are out on the terrace or in a front room warmed by a wonderful fire framed by a local marble fireplace. Needless to say, the meals are seriously delicious.

Sainte Valière

Sainte Valière, from one of the many vineyards surrounding the village

My two-week residency flashed past but it was the perfect place to get down to working really hard. I wanted to complete two big silverpoint drawings for an upcoming exhibition and this was the ideal situation simply to push through and finish them in dogged fashion. My quiet and privacy were respected delightfully.

So many enticing trips, nonetheless, beckoned. Sainte Valière is in bounteous wine-growing country, a world punctuated by blue mountain ranges, dwarfed – one has to admit – by the snow-capped Pyrenees peaks floating in the distance to the south west. Lovely golden-stone villages all have their own “caves” or wine-growers where wine-tasting is offered, plane tree avenues shade and wind along roads that invite the explorer. The Canal du Midi, serene and winding in stately fashion though the vineyards and past small towns that have known considerable wealth from the canal transport and commerce in the past, is now bringing new economic activity to the area. Biking, boating, small restaurants along the water – so many attractions to delight, and all close enough to hand to Sainte Valière that an artist can slip off for a while to change gears from creating to celebrating life in France.

Bridge over the Canal du Midi at nearby Le Somail (image courtesy of Peter Gugerell, Vienna, Austria)

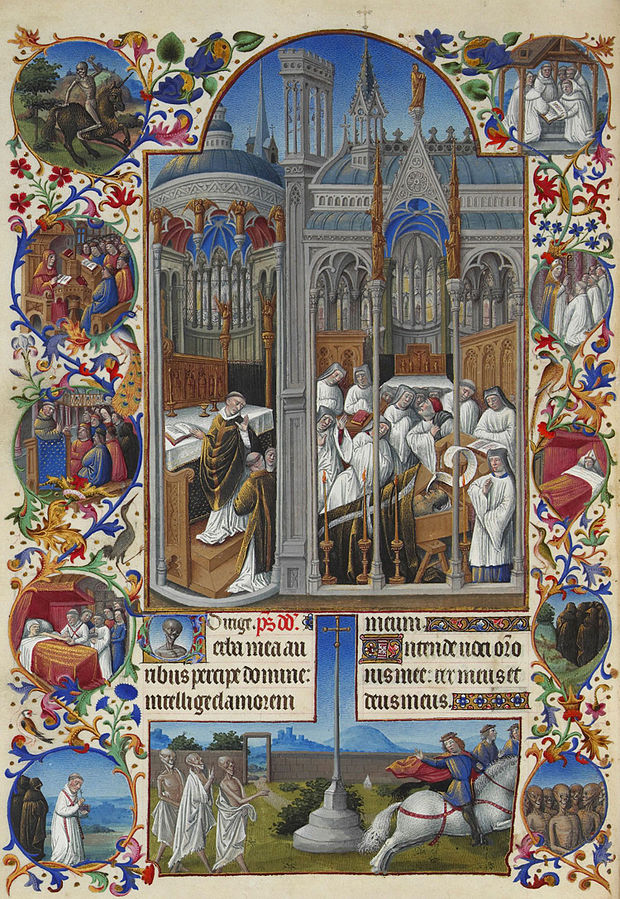

Another wonderful side trip from Sainte Valière is the Abbey of Fontfroide, a mighty Cistercian twelfth century monastery that was restored and reinvigorated at the turn of the 20th century by Gustave Fayet. Art lovers know his name as a major late 19th century collector of Gauguin and other contemporary artists. He was a wine grower from the area, an artist himself, painting and creating lovely ceramics and carpets. He was also an experimenter in the astonishing stained glass windows that he and a master glazier, Richard Burghstal , created for the church and dormitory at Fontfroide.

Abbey of Fontfroide, south of Narbonne, France - the entrance

Abbey of Fontfroide

Not only is the abbey itself beautiful, with its rose garden and hillside gardens framing it as it nestles the forest-clad valley in the Corbières hills, but its library hides another gem. Gustave Fayet commissioned Odilon Redon to paint two huge canvases, each of three panels, in the vast stately library above the cloisters. Night and Day, they are considered his ultimate masterpiece. Complex, highly allusive and full of symbols, they are a symphony of colour and lyricism. A special guided visit to see them is well worth the effort; in truth, they are so many-layered that one could see them innumerable times and see something fresh each time.

Night, Odilon Redon, 1910-1911, one of the two paintings in the Library, Abbey of Fontfroide, France

Day, Odilon Redon, 1910-1911, one of the two paintings in the Library, Abbey of Fontfroide, France

Narbonne and Carcassonne are other visits well worth making as excursions from Sainte Valière. But – remember –Hôtel Sainte Valière is an artist’s residency! So, ideally, the creative juices should flow too and the side trips can be the rewards. I certainly found that to be the case. As I rolled my two big silverpoint drawings in a tube to pack and take home, I felt I was packing far more than art. The two weeks were a gift of gracious living, fascinating regional beauty and, best of all, the formation of new and delightful friendships.