Down the ages, man has historically turned to the surrounding world to create a virtual reality in art, through the complex interplay of what the eyes perceive, how the colours have impact and what emotions are invoked. In other words, artists have used the world around them as the major source of their artistic inspiration and subject matter.

After the invention of photography in the decades before 1850, the basis for art making changed. As Henri Matisse observed, "The invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature," which enabled the artist "to present emotion as directly as possible and by the simplest means."

La Danse (I), Henri Matisse, 1909. Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Indeed, after the mid-19th century, artists' experiments grew more and more divorced from nature in many instances. Monet, for instance, still based his work on nature but it was often a very different vision and interpretation of nature, which meant, of course, that he was regarded as a main innovator in the new school of Impressionism.

Impression, soleil levant, 1872, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris

Water Lilies, 1920, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London

As the years passed and artists grew less and less interested in the old, academic way of depicting the world around them, experiments multiplied. Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cezanne, then Picasso, amongst others, led the way to an art that put more emphasis on colour, emotion and thus a psychological impact. Cezanne compressed, distorted, changed perspective, volumes, relationships, colour relationships and played such games with "reality" than he was viewing in his surrounding world that we are still indebted to him in terms of interpretation of subject matter. He stared and stared at his subject matter, but then he in essence produced metaphors about the nature he was looking at; he was "a total sensualist. His art is all about sensations", said Philip Conisbee, curator at The National Gallery, who put together an exhibition of Cezanne's work in 2006.

Le Pont Des Trois-sautets, watercolor and pencil, Paul Cézanne, c. 1906, Cincinnati Art Museum

Beyond Cezanne, of course, the art world turns to Cubism, abstraction and any number of other forms of presenting emotion directly andurgently, leaving behind any remote reference to a virtual reality of the world. Photography's invention as a "liberation from reality" indeed, for a time, ensured that artists used a very different language to convey aspects of their world. Georges Braque was one such artist.

Violin and Candlestick, Georges Braque, Paris, spring 1920, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

After Piet Mondrian's early experiments with Cubism, his path led to works that have become iconic.

Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow, 1937-42, Piet Mondrian, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London

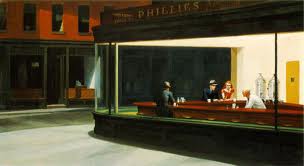

As the 20th century advanced, artists strayed further and further away from their surrounding reality, totally divorced from it by photography's invention - whether the artists were conscious of this fact or not. But then, of course, the pendulum began to swing back the other way as perhaps, artists began to run out of ways to express themselves that were truly new and different abstractions. So photography comes back into play, manipulated and used in new and sophisticated ways to depict realities. Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Audrey Flack and many others, especially in the United States, have worked in amazing ways that also built on Edward Hopper's reclusive reality that had been a more lonely stream of 20th century art in America..

Night Hawks, Edward Hopper, 1942, oil on canvas (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Richard Estes “Columbus Circle Looking North,” 2009 Oil on canvas, 40 inches by 56 1/4 inches. Linden and Michelle Nelson Tenants by the Entirety © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

And so the circle is closed and artists once more have recognised the potential of photography in making art. Indeed there are many artists who predicate their depiction of the world around them on photographs, even, in some cases, to tracing images onto canvas. Nonetheless, even their interpretations of reality have been influenced by the long deviations in art-making, away from the need to copy reality. We are all heir to what has gone before us.