While I was wandering through London’s National Portrait Gallery recently, following the meandering trail through the rooms to view the exhibit Simon Schama curated of the sixty portraits in “The Faces of Britain”, I was totally fascinated. Not only because there were so many portraits, in so many media, of icon faces of recent times, but because a quote kept ringing through my head.It was a statement in a National Geographic Magazine article in August 2014 on “Before Stonehenge”: “Art offers a glimpse into the minds and imaginations of the people who create it.” This seemed to be so appropriate of the art I was seeing as I followed the “Faces of Britain” exhibit as it was scattered (cunningly, I decided!) through the galleries. Not only were the faces diverse, interesting and evocative of the people depicted, but the actual art created spoke volumes too about the artists, their perception of the portrait’s subject and the times in which the work was created in each case.

Read MorePainting

The Intensity of Size - Big or Small in Art /

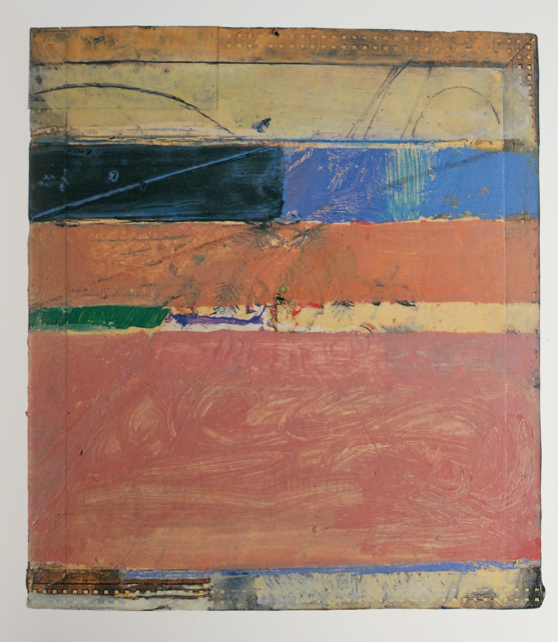

When I went to see the Richard Diebenkorn survey at the Royal Academy in London recently, I found it interesting but was surprised at my lack of excitement at seeing most of the work. The Ocean Park series on display were, of course, the most lyrical, but again, I was reminded of an internal conversation I frequently have with myself. Does a really big canvas manage to convey the intensity of the artist's passion? Or does the sheer size become, in many cases, a path to dilution of that excitement and energy? If you have to go on labouring day after day to paint huge surfaces, do you run out of steam? Of course, it is not always the case by any means — think of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, when Michelangelo laboured day after day in the most difficult of physical positions and conditions, and yet he achieved a power and impact of work that reverberates for every viewer.

Nonetheless, not every artist is a Michelangelo. And in the case of Richard Diebenkorn, I personally found that all his large canvases began to lack intensity. My reaction to these works was unexpectedly reinforced by three small paintings hung amongst the Ocean Park canvases.

They were three equally abstract works, painted on small cigar box covers. He used the cigar box cover paintings as gifts to friends, apparently, and my feeling was that these were the true gems in the exhibition. They were the perfect epitome of "small is beautiful". AsSarah C. Bancroft, curator of one Diebenkorn museum exhibition observes in the catalogue essay, they “capture one’s attention from across the room and command an expanse of wall space disproportionate to their actual size.”

Lyrical, free, certainly intense, but utterly lovely - they just sang. The more one explores the work Diebenkorn did in this small format, on cigar box lids, the more delightful and intimate the body of work becomes. Perhaps Diebenkorn felt liberated in this small format - he was not constrained by acres of canvas, nor the demands of gallery settings and collectors demanding impressive pieces. He could just create small delights that are intimate in scale, where his true sense of colour and the fitness of abstraction could be married to an acute sense of human celebration of life.

As Diebenkorn himself observed, "The idea is to get everything right — it’s not just color or form or space or line — it’s everything all at once." He certainly achieved that for me in the cigar box lid paintings.

The three large rooms of the Royal Academy's Diebenkorn exhibition were distilled down to these three small pieces, for me. In a funny way, they helped me feel more reassured about my own art - my frequent choice of small format in metalpoint drawings was strangely validated. I was grateful to Diebenkorn for that, but most of all, for three paintings that still sing to me weeks after seeing them.

Tiny Images, Vast Scenes /

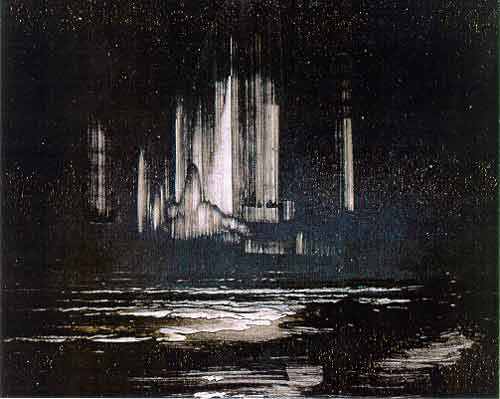

The Tempest, Peder Balke, 1862

Peder Balke is not the name of an artist that readily springs to mind, yet he is now considered the pre-eminent Norwegian artist of the 19th century. His landscapes and especially seascapes, highly unusual in their techniques, are now justly celebrated. I was lucky enough to see an exhibition of his paintings at the National Gallery, having seen a smaller one of his work in the same rooms four years ago. Balke lived from 1804-1887, started out as a full-time painter and then had to turn to other ways of earning his living. Nonetheless, he continued to paint, for his own pleasure, experimenting and using paints in ways that heralded modern expressionism. He travelled to the North Cape in Norway, an area of dramatic coastlines and radiantly strange light of the Arctic Circle. These scenes continued to influence him many years later. He did not always paint specific scenes, but used the moods and impressions of nature, often in almost abstract fashion, to convey the majesty, mystery, solitude and power of the natural world.

While the larger paintings on display in the National Gallery exhibition were impressive, especially the highly atmospheric ones of Northern scenes, done in the 1870s, the ones that fascinate me are the tiny ones. They pack a punch, almost in a visceral way.

They are indeed small, mostly blacks and white, seascapes and some landscapes of glaciers or waterfalls, often almost abstracts. They are not small, however, when it comes to impact. Their effect is perhaps more powerful than that of many of the larger paintings he did. Perhaps my love of monochromatic works leads me to them, but to me, they are stunning in their big voices coming from very small rectangles of oil on cardboard or oil on board.

I wonder if other people find them as arresting as I do?

"A-ha" Moments in Exhibitions /

Do you ever experience a wonderful moment when you see something in an exhibition, it suddenly resonates and explains some connection, or gives an unexpected insight into something else? I love those moments. I had a few such instances during my exhibition "orgy" in London recently. The first one came as I was marvelling at Goya's drawings in the superb "Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album" at The Courtauld Gallery. This exhibition was the first reconstruction of the dispersed 23 drawings from Francisco Goya's so-called Album D, "Witches and Old Women, produced during the wonderfully productive last decade of his life, together with other related drawings and prints.

The exhibition was riveting in every way - Goya's economy of drawing, his powers of depicting human emotions in their most raw and dramatic forms, his mordant commentaries on human foibles, all so simply done on small sheets of paper, in shades of ink - oh heavens! The scholarly work done that permits the reconstruction of this album, in a coherent and likely order of drawings, was also most fascinating and impressive.

Then, in the works accompanying the 23 drawings, there was a brush and brown ink drawing from Album B, Estas Brujas lo diran (Those Witches will tell).

I was so astonished. The line from Goya ran straight and true to Egon Schiele's Self Portraits. Goya's drawing is a haunting image of a naked old witch devouring snakes. Egon Schiele's Self-Portraits tell of equally disturbing solitary states of mind.

Both artists are fluid in their lines, their vigorous treatment of wet and dry passages of drawing media. Did Schiele know of Goya's drawing in the Prado? Or was it just happenstance, the result of two gifted draughtsmen's states of mind?

Another "aha" moment for me that stands out in my memory was when I was looking at one of several unusual Claude Monet paintings in "Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market" at the National Gallery. In the gallery showing works by Monet that Durand-Ruel had exhibited in a pioneering monographic show in 1883, , there was an arresting painting of two apple tarts or galettes on wicker platters, Les Galettes, painted in 1882 and in a private collection today.

Its vigour and brio of treatment, its golds and yellows and close-cropped composition all take one straight to Vincent Van Gogh and his sunflowers or even a study of humble fishes, or bloaters. Did he see Monet's study of the Galettes - he most probably did, as he produced the first studies of cut sunflower heads some five years later.

The third moment of fascination for me was in the same Impressionist exhibition, again a Monet painting done in 1875, The Coal Carriers. Monet had seen workers unloading coal for the Clichy gasworks from the train from Argenteuil to Paris, and painted this work partly from memory.

The rhythmic placement of the men on the gangplanks, the silhouettes and dark colours somehow reminded me of many of the Japanese ukiyo-e prints, their rhythms and cropped views. Monet was an avid admirer of the new wave of Japanese prints coming in to Paris at that time.

I love these moments when you can link up artists, influences and inspirations. They validate one's own endeavours as an artist as you study and view other artists' works, not to copy, but to use as pathways to grow and spread wings.

Rediscovering Charlotte Salomon /

Charlotte Salomon works

One of the wonderful things about spending time at an artist residency is being able to alternate between trying to create art and reading about other artists. It is a luxury to do so, and I am savouring it at a beautiful and peaceful retreat nestled in the foothills of the French Pyrenees, Bordeneuve, in Betchat, Ariège. I am a firm believer in the eddying delights of chance, especially when it comes to happening upon books. Once again, Lady Luck led me to a book, "Charlotte" by David Foenkinos, published last year by Gallimard and which won the 2014 Prix Renaudot and Prix Goncourt des Lycéens.

It is a fictionalised account of the life of Charlotte Salomon, the young German Jewish artist who fled to France during World War II and there was finally killed in Auschwitz in 1943. Written in verse, it is an arresting account of the intertwining of the author's fascination for this artist with the account of her young life.

I knew of Charlotte Salomon and her haunting, passionate paintings, but this book made me go back and look more closely at images of her work. As the Nazis tightened their noose on the Jews, life - everyday, intellectual, professional and cultural - became increasingly impossible, but Charlotte's prominent physician father and diva singer step-mother refused to leave Berlin. So Charlotte eventually took refuge in art, her passion and her solace.

From there, her life grew more complex, more dangerous. Once she had fled to France, leaving behind her family and a man with whom she had fallen passionately in love, she shut herself up in a hotel room in Villefranche for two years. There she created a vast body of work autobiographical in nature, almost operatic in form, with dialogue, images, commentary, musical cues, all vivid in colour and content. Pregnant and in mortal danger, she eventually entrusted her art to her physician, knowing that she only had a short time to live. She gave him a simple, stark explanation, "This is my whole life".

Eventually in 1961, her work, Life? or Theatre?: A Play with Music, was exhibited for the first time. The exhibit and accompanying catalogue spread the word about her inventive, passionate art. Now there is a new surge of interest after David Foenkinos' book has been published. I am glad I have been reminded of this courageous, highly original and driven artist who only lived twenty-six years.

Music in Lyrical Colours: Erdmute Blach's Art /

Every time I go to an artist residency, there are so many rewards beyond actually having the opportunity to create art pretty well full time.

Yesterday I had one such reward: listening to a talk given by fellow resident artist, Ermute Blach, about her work.

Erdmute comes from Germany, initially from East Germany before unification, and now she lives in a small town, Rostock. But her art is anything but small town. Despite her quiet demeanour, her work is powerful, lyrical and arresting.

We have a lot in common in our attitudes to being artists, the first being that each of us started life in fields other than art. In Erdmute’s case, she has a degree in mathematics. Yet, to my way of thinking, the discipline and logic of mathematics lead very readily to one of the main sources of inspiration for her paintings and drawings: music.

Erdmute uses the nuances and layers of compositions – mainly music written by contemporary composers now – as the means by which to express her love of form and colour. She works directly with musicians, including Portuguese musicians, and composers, sometimes in live performances.

Her acrylic paintings are bold and direct, expressing very clearly the rhythm, content and passion of the pieces of music she is evoking. Interestingly, she does not listen to the actual music as she is painting; she often knows the score already, but it plays only in her head as she works.

Another love which inspires her painting is poetry. She has created artist books of poetry and had them published by one of Germany’s major art book publishers, Edition balance. The Frankfurt Book Fair and the Leipzig Book Fair have been recent venues where her art books are on display.

Here at Obras Portugal, she is using her residency to create a large body of work inspired by the Portuguese Alentejo landscapes and world. These works will be exhibited next years, 2015, in the nearby wonderful city of Evora.

Erdmute Blach - exhibited acrylics

So Erdmute is again responding to the sights and sounds, the rhythms and intervals; already on the walls here in the studio, bold colour is singing.

A delicious reward for me, listening to Erdmute talk of her work, thoughtfully, seriously, passionately. It makes me glad to be a fellow artist.

After the Invention of Photography /

Down the ages, man has historically turned to the surrounding world to create a virtual reality in art, through the complex interplay of what the eyes perceive, how the colours have impact and what emotions are invoked. In other words, artists have used the world around them as the major source of their artistic inspiration and subject matter.

After the invention of photography in the decades before 1850, the basis for art making changed. As Henri Matisse observed, "The invention of photography released painting from any need to copy nature," which enabled the artist "to present emotion as directly as possible and by the simplest means."

La Danse (I), Henri Matisse, 1909. Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Indeed, after the mid-19th century, artists' experiments grew more and more divorced from nature in many instances. Monet, for instance, still based his work on nature but it was often a very different vision and interpretation of nature, which meant, of course, that he was regarded as a main innovator in the new school of Impressionism.

Impression, soleil levant, 1872, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the Musee Marmottan Monet, Paris

Water Lilies, 1920, C. Monet. Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London

As the years passed and artists grew less and less interested in the old, academic way of depicting the world around them, experiments multiplied. Gauguin, Van Gogh, Cezanne, then Picasso, amongst others, led the way to an art that put more emphasis on colour, emotion and thus a psychological impact. Cezanne compressed, distorted, changed perspective, volumes, relationships, colour relationships and played such games with "reality" than he was viewing in his surrounding world that we are still indebted to him in terms of interpretation of subject matter. He stared and stared at his subject matter, but then he in essence produced metaphors about the nature he was looking at; he was "a total sensualist. His art is all about sensations", said Philip Conisbee, curator at The National Gallery, who put together an exhibition of Cezanne's work in 2006.

Le Pont Des Trois-sautets, watercolor and pencil, Paul Cézanne, c. 1906, Cincinnati Art Museum

Beyond Cezanne, of course, the art world turns to Cubism, abstraction and any number of other forms of presenting emotion directly andurgently, leaving behind any remote reference to a virtual reality of the world. Photography's invention as a "liberation from reality" indeed, for a time, ensured that artists used a very different language to convey aspects of their world. Georges Braque was one such artist.

Violin and Candlestick, Georges Braque, Paris, spring 1920, Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

After Piet Mondrian's early experiments with Cubism, his path led to works that have become iconic.

Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow, 1937-42, Piet Mondrian, oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London

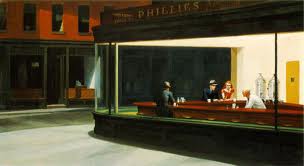

As the 20th century advanced, artists strayed further and further away from their surrounding reality, totally divorced from it by photography's invention - whether the artists were conscious of this fact or not. But then, of course, the pendulum began to swing back the other way as perhaps, artists began to run out of ways to express themselves that were truly new and different abstractions. So photography comes back into play, manipulated and used in new and sophisticated ways to depict realities. Richard Estes, Chuck Close, Audrey Flack and many others, especially in the United States, have worked in amazing ways that also built on Edward Hopper's reclusive reality that had been a more lonely stream of 20th century art in America..

Night Hawks, Edward Hopper, 1942, oil on canvas (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

Richard Estes “Columbus Circle Looking North,” 2009 Oil on canvas, 40 inches by 56 1/4 inches. Linden and Michelle Nelson Tenants by the Entirety © Richard Estes, courtesy Marlborough Gallery, New York

And so the circle is closed and artists once more have recognised the potential of photography in making art. Indeed there are many artists who predicate their depiction of the world around them on photographs, even, in some cases, to tracing images onto canvas. Nonetheless, even their interpretations of reality have been influenced by the long deviations in art-making, away from the need to copy reality. We are all heir to what has gone before us.

Art Discoveries for the New Year /

After a long hiatus in posting because of family health concerns, it is good to start thinking a little about art and the art world. For me, art spells energies, health, healing and fascinations, together with beauty, stimulation and amazements.

There are always sparks of interest that one discovers when one can slip back through the doors into the art world. I love these tiny sparkles - they somehow help explain the bigger picture, often in an indefinable way.

My first discovery for the New Year - and a belated Happy New Year to all who read this - came during a visit to Savannah's Telfair Museums' current exhibition, Offerings of the Angels: Treasures from the Uffizi Gallery.It is a show which comes across as a rather thin selection of storeroom religious paintings, but, as always, there are interesting aspects. The most fascinating was a small painting on copper by Alessandro Tiarini (1577-1668, Bologna).

The Nativity, oil on copper, 1650s, Tiarini, 13 x 16.8 inches

I rounded a corner in the exhibition, and to my fascination, found another work that was painted on an entirely different surface, slate.

Christ Carrying the Cross, S.Del Piombo , 1535-1540 Oil on slate, 118 x 157 cm, Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest, Hungary)

Often, the artists who followed Piombo's example used the natural darks of the stone for their darks, thus eliminating the need for preparatory layers. In the Uffizi exhibit, there was another example of this: Alessandro Turchi (known as L'Obetto, 1578-1649) used dramatic chiaroscuro effects in his "Christ in Limbo", ca. 1620, which was painted on gleaming hard black jasper. Sometimes he also used black marble in the same fashion.

The alternative surface Piombo experimented with, copper, was already in use for etchings and engravings. Copper plates come in small sizes, and have the great advantages of ensuring there are no cracks, or craquelure, in the oil paint, as well as the ability to paint in minute detail. It has proven a very stable and long-lasting support for painting. By the end of the 16th century, Dutch landscape painters in Rome had adopted this support enthusiastically, and the use spread via Italians to other cities, such as Bologna. Already this form of painting had been shared with their Northern compatriots in the Netherlands and Flanders. Jan Breughel I painted a lot on copper, as did Peter Gysels, Osias Beert I, Frans Snyder, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Joachim Wtewael and Jan van Kessel amongst others.

Jan Brueghel I, "View of a City and River", Oil on Copper, 1578.

Jan Brueghel I, "Restbreak while Escaping Egypt", Oil on Copper

Jan Brueghel I, Still Life, Oil on Copper

Osias Beert I, "Still Life of Oysters, Sweetmeats, and Dried Fruit", Oil on Copper, 1609

he Golden Age, 1605, Jaochim Wtewael (1566–1638), oil on copper, Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum

The Dutch were marvellous exponents of oil on copper paintings, especially in their heyday. Even Rembrandt tried his hand at painting on copper when he was in his early twenties; this is a recently re-discovered painting by him.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669) Rembrandt Laughing. Oil on copper, about 1628. 8 3/4 x 6 3/4 in private Collection.

Later, another wonderful still life painter, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, tried his hand at painting on copper.

Chardin, Fast-Day Meal, 1731, Musee du Louvre (France) Oil on copper, Height: 33 cm (12.99 in.), Width: 41 cm (16.14 in.)

Many other artists have painted works on copper, from El Greco (the "Adoration of the Shepherds", 1572-74) to Juan Sanchez Cotán, the famed 17th century Spanish painter of still life, who tried this small religious painting (acquired by the San Diego Museum of Art in 1990).

Saint Sebastian, oil on copper painting by Juan Sánchez Cotán, after 1603

My New Year discovery has given me delight and led me back to art that I have loved over the years when I stumbled upon such works in divers museum exhibitions. Jan van Kessel is one of the artists whose work on copper has most enchanted me. See what you think.

Butterflies and other Insects, 1661, oil on copper, 19.1 x 28.9 cm. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum

Butterflies and other Insects, 1661, oil on copper, 19.1 x 28.9 cm. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum

Jan van Kessel, Drawings of insects, c. 1653, Oil on Copper

Jan van Kessel, Drawings of insects, c. 1653, Oil on Copper

I have been looking to the past for works of art on copper. Perhaps it is also part of the New Year discoveries to explore the beautiful art that is being created on copper today. Even the trade group, the Copper Development Association, has interesting pages on such art-making. Happy exploring!

Watercolor Magic /

Mary Whyte is a watercolourist whom I have long admired, ever since I saw her work at her husband's gallery, Coleman Fine Art, in Charleston, South Carolina. It was thus a treat to be able to see a large body of her work, Working South, currently on display at the Telfair Museums in Savannah, Georgia.

Trap, Crabber, Pinpoint, GA, watercolour on paper, 2008, 30 x 38, image courtesy of Mary Whyte

The exhibition apparently grew out of one of those lucky coincidences and flashes of inspiration: she was painting a portrait of a Greenville banker and they were commenting on the number of lay-offs announced in the local textile mills. A chance reply to her about the fact that in ten years, all the mills would be gone sparked the idea to record and paint people who were working in the large number of disappearing occupations; from crabbers and textile mill workers to loggers and small hog farmers. Mary Whyte set out to find and paint workers in these different worlds in the South. Three years of work produced the exhibition now at the Telfair.

There is a felicitous mixture of large finished watercolour paintings and the small studies and preparatory drawings on display. It is always good to see how careful preparations and study, learning about the people, the places, the look and feel of a subject, with accompanying journal notes, small drawings and paintings, help ensure a good result in the final work of art. It is a salient point we all ought to register as artists!

New Year, watercolour painting of a milliner from Atlanta, GA; 2009, 22 1/2 x 29, image courtesy of Mary Whyte

What is also fascinating and impressive about these watercolours is their combination of tight realism in faces, hands and arms for each portrait, and then the fluid, abstract use of watercolour's rich capacity to meld and swirl billows of colour in other parts of the painting. Underpinning all this skill is, in each case, a sense of dramatic, arresting composition, an arrangement of shapes that goes to the essence of the occupation or industry Whyte is depicting.

Crossing, Ferryboat captain, Valley View, KY, 2009, watercolour, 15 x 30, image courtesy of Mary Whyte

Eclipse, tobacco farmer. Gretna, VA, watercolour, 2009, 22 x 30, image courtesy of Mary Whyte

One of the most interesting of these paintings, for me, was this highly evocative depiction of elderly musicians marching to honour the dead in this Miami, FL, cemetery, a custom that is almost gone. Whtye's ability to go from tight, detailed realism to the most diaphanous of "mists" of colour, melding bodies and ground, with the mighty banyan tree as abstract counterpoint, was impressive.

Pilgrimage. Funeral band, Miami, FL. watercolour, 2009, 39 x 48, image courtesy of Mary Whyte

Perhaps the most valuable remark - for fellow artists as well as for viewers - that Mary Whyte makes in the book accompanying the exhibition, Working South; Paintings and Sketches by Mary Whyte, is : "true art is not about copying. Every painting is an invention. Each painting we make is about our observation and the feeling about what we are seeing. Not one painting represented in this book is exactly what I saw, but each is exactly what I felt." (page 8)

This exhibition is well worth visiting - several times!

Attitudes about Flower Painting /

I have always been interested to listen to the "intonations" with which people speak or write about flower paintings. Floral art has often had a difficult time ascending high on the ladder of art appreciation, in circles of art officialdom.

Despite flower painting having illustrious beginnings from the 16th century onwards, with Northern Renaissance Dutch and Flemish artists, flower painting has historically been associated with amateur lady painters who pursued art as a pleasant, genteel past time. Very few male artists have painted flowers as their main subjects - Manet, Renoir, Monet, Van Gogh and other 19th century artists did some wonderful paintings of flowers, very much as still life. This painting done in 1883 by Edouard Manet is a perfect example.

Carnations and Clematis in a Crystal Vase, Edouard Manet, 1882, (image courtesy of the Musee d'Orsay).

Henri Fatin-Latourwas one of the most amazingly passionate painter of flowers, again as still life. These artists did however observe the flowers carefully and closely, and knew how these plants grew.

H. Fatin-Latour, White Roses, 1875, (Image courtesy of York Art Gallery, York, UK)

Other later male artists, from Picasso to Matisse and beyond, occasionally painted or drew flowers, but often, the results were more generic.

Matisse, Flowers, 1945

Meanwhile, women artists were creating beautiful "portraits" of plants and flowers, many using the botanical approach as their springboard.

Ellis Rowan was travelling through Australia and South East Asia in her quest to paint brilliant and exotic flora. Perhaps the conscious or unconscious links between gardening and flower paintings in British circles helped foster the interest in such art in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa as well as Great Britain.

Carolina Jessamine, Gelsemium sempervirens, Ellis Rowan

Another wonderful result of celebrating a garden was the art Childe Hassam created in Celia Thaxter's garden on the Isle of Shoals, Maine. This is one such painting Hassam did in 1890, now in the Metropolitan Museum.

Celia Thaxter's Garden, Childe Hassam, 1890, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

Despite all these - and many, many other - instances of superb floral paintings, I cannot help being aware of a certain tone when such art is talked to in today's art world. Almost a sneer, not quite? As if paintings about flowers are, really, not quite "up to snuff". Despite a huge renaissance of botanical art (mostly done, need I say, by women artists), despite the trail blazed so memorably by Georgia O'Keeffe with her sensual, strong interpretations of flowers, there is still a je ne sais quoi in the air on the subject of floral art.

G. O'Keeffe, Two Calla Lilies,1928 (Image courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art)

This attitude fascinates me because, as I struggle to draw or paint flowers, I realise, repeatedly, that tackling flowers as a subject is very complex. In fact, just as challenging a subject as nudes, landscapes or anything else that are considered more "serious". By the time that an artist has mastered the intricacies of plants, their flowers and leaves, he or she is pretty capable of tackling any other type of art subject imaginable, and in any medium..

Maybe the decades when drawing was considered unnecessary contributed to the dismissal of flower-based art. Perhaps today's emphasis on conceptual art also is a factor, with the overtones of floral paintings lacking "gravitas" and deeper meanings. It is however ironic that part of the art world is so dismissive of floral painting, because another, large part of the art-loving world is very happy to embrace it.

Just as well, I conclude. Think what complexities and delights artists would miss if they never looked closely at a flower!.