When I went to see the Richard Diebenkorn survey at the Royal Academy in London recently, I found it interesting but was surprised at my lack of excitement at seeing most of the work. The Ocean Park series on display were, of course, the most lyrical, but again, I was reminded of an internal conversation I frequently have with myself. Does a really big canvas manage to convey the intensity of the artist's passion? Or does the sheer size become, in many cases, a path to dilution of that excitement and energy? If you have to go on labouring day after day to paint huge surfaces, do you run out of steam? Of course, it is not always the case by any means — think of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, when Michelangelo laboured day after day in the most difficult of physical positions and conditions, and yet he achieved a power and impact of work that reverberates for every viewer.

Nonetheless, not every artist is a Michelangelo. And in the case of Richard Diebenkorn, I personally found that all his large canvases began to lack intensity. My reaction to these works was unexpectedly reinforced by three small paintings hung amongst the Ocean Park canvases.

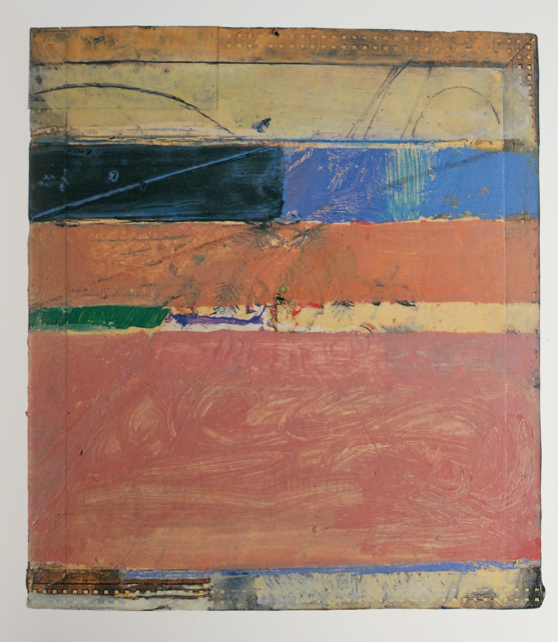

They were three equally abstract works, painted on small cigar box covers. He used the cigar box cover paintings as gifts to friends, apparently, and my feeling was that these were the true gems in the exhibition. They were the perfect epitome of "small is beautiful". AsSarah C. Bancroft, curator of one Diebenkorn museum exhibition observes in the catalogue essay, they “capture one’s attention from across the room and command an expanse of wall space disproportionate to their actual size.”

Lyrical, free, certainly intense, but utterly lovely - they just sang. The more one explores the work Diebenkorn did in this small format, on cigar box lids, the more delightful and intimate the body of work becomes. Perhaps Diebenkorn felt liberated in this small format - he was not constrained by acres of canvas, nor the demands of gallery settings and collectors demanding impressive pieces. He could just create small delights that are intimate in scale, where his true sense of colour and the fitness of abstraction could be married to an acute sense of human celebration of life.

As Diebenkorn himself observed, "The idea is to get everything right — it’s not just color or form or space or line — it’s everything all at once." He certainly achieved that for me in the cigar box lid paintings.

The three large rooms of the Royal Academy's Diebenkorn exhibition were distilled down to these three small pieces, for me. In a funny way, they helped me feel more reassured about my own art - my frequent choice of small format in metalpoint drawings was strangely validated. I was grateful to Diebenkorn for that, but most of all, for three paintings that still sing to me weeks after seeing them.