I have been slowly reading an extraordinary tome while I listen to the early morning birdsong greeting the sunrise.

It is a huge book, but well worth reading: The Primacy of Drawing by Deanna Petherbridge is the result of ten years’ research and careful thought about drawing, in all its implications and manifestations.

With wonderful illustrations of drawings from a multitude of public and private collections, Dr. Petherbridge delves into all the aspects of historical and contemporary drawing approaches and philosophies.

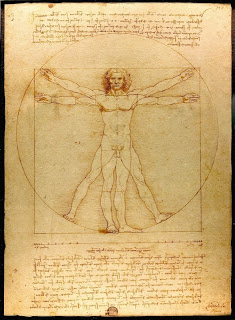

Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, Galleria dell' Accademia, Venice (1485-90)

Leonardo da Vinci was one of the most notable of the Renaissance artists to combine art with science in his endless quest to learn about the world around him. Other artists, for centuries, have used life drawing, from casts or live models, as a way of learning about the human body and honing their artistic skills.

Life drawing class. c. 1890, (Photo courtesy Leeds Museums and Galleries (Art Gallery))

Deanna Petherbridge discusses many interesting approaches to drawing, but one summation, at the end of a chapter on “Drawing and Learning”, struck me as very apposite indeed in today’s world. I quote it in full, with thanks to its author:

"Learning to observe, to investigate, to analyse, to compare, to critique, to select, to imagine, to play and to invent constitutes the veritable paradigm of functioning effectively in the world.” (My italics.)

I think that every teacher should think hard about including art, and especially drawing, in the preparation of today’s generations in school, college and university.

Everyone would benefit, now and in the future.