Three exhibitions in New York, each by a superb artist in a different century, but all united by a lifelong passion to draw, draw, draw, anything and everything. For an artist, these current exhibitions are a wonderful reaffirmation of the central role drawing potentially plays in the development and creativity of an artist. Gainsborough, Delacroix, Wayne Thiebaud - three very dissimilar artists, yet they are all on the same page in a drawing book.

Read MorePlein Air

Recurrent Themes in An Artist's Work /

Olive trees are an integral part of the Mediterranean landscape, and they have been a recurrent theme in many artists' work. Sacred trees since early Greek times, they are astonishing in inspiration, as well as generous in their fruit and oil. No wonder artists love to celebrate these astonishing and often very ancient trees.

Read MorePaul Cézanne's Drawings /

The exhibition, "The Hidden Cézanne; From Sketchbook to Canvas" is still on until September 24th, 2017, at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland. Cézanne's drawings, kept very private during his lifetime, tell of his questing, learning, thought processes in creating art or just recording for inspiration much later on. It reminds us all that drawing is a pathway to many ways of analysing, understanding and forging an artistic identity that is unique.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 5) /

When John Singer Sargent painted this scene of Claude Monet working en plein air, he recorded the heyday of the Impressionists' love of working outdoors to record and celebrate nature. Ever since, there has been a long list of wonderful plein air artists on every continent, and we artists, living today, have a rich heritage of landscape art from which to be inspired. This is the final Part 5 of my blog entry on Plein Air Art- Looking Back.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 4) /

The 19th century saw a flowering of plein air art in Europe and in this part of my blog-series on Plein Air Art - Looking Back, I had fun trying to select images that could celebrate this explosion of energies and talent. We owe a great deal to those artists as they broke with academic tradition and painted as their hearts dictated.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 3) /

In Part 3 of Plein Air art - Looking Back, I follow the development of plein air art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe as so many artists paved the way for present-day interpretations of nature and the outdoors.

Read MoreJoaquín Sorolla and the Sea – Part II /

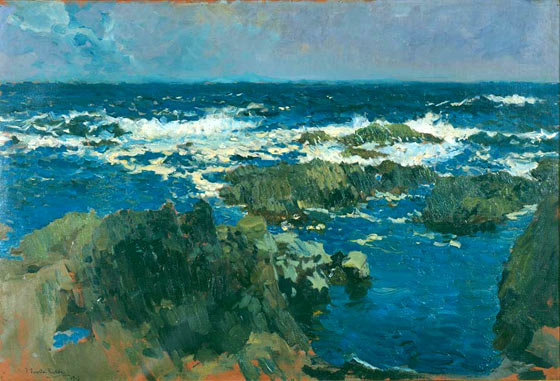

My last blog post was on Joaquín Sorolla's approach to plein air painting, after I saw the CaixaForum exhibition, "The Colour of the Sea" in Palma de Mallorca. His "Colour Notes" are so fresh and searching, so bold and gestural, that I sometimes felt that the resultant paintings, in which this carefully observed material was incorporated, lost a little in impact. Nonetheless, the exhibition shows beautifully how Sorolla, set up on the beach in very practical painting fashion, was ever-intent on capturing the endless changes of the seascapes. His meticulous studies of the different hues of blue, for instance, show his passion for capturing the limpid colours of the sea, the play of light on the waves or on bodies in the water, their diversity of tone. Yes, he was basing all his art on Nature, in a realistic fashion, but he certainly was breaking down what he saw into the most abstract of shapes and compositions.

Look, for instance, at the Young Swimmers. Their skin underwater becomes a shimmer of alabasters floating in this energy-filled abstraction of green ripples and dancing light.

Another canvas that interested me in the flattening of the perspective is Marie at the Beach. As in other paintings he did of contrejour light on cliff tops, Sorolla flattened out the distances: the sea below is virtually on the same plane as Maria, because one senses his total fascination with the sea and its restless play of light and foam.

The translucence of white fabric, seen contrajour against the sea, is another of his favourite subjects. Just out of the Sea demonstrates this marvellously; it is all about that luminous, undulating light blowing in the wind, contrasting with the glowing solidity of the mother and small boy, all rendered tangy in the salt air and the susurration of the turquoise sea.

The marine landscapes are all about luminosity, distance being dissolved into pure colour. Sky and sea are his fascinations, his challenges. No wonder he stated, ""I could not paint at all if I had to paint slowly. Every effect is so transient, it must be rapidly painted.”

His 1919 works done at Cabo San Vincente in Mallorca are pure colour hymns. No wonder he is loved by so many for these celebrations of the sea, one of Spain's greatest beauties in his lifetime. We are lucky that he recorded his country's coastal scenes before they were transformed by 20th-century mass tourism.

Joaquín Sorolla and the Sea - Part I /

An exhibition, "Sorolla: The Colour of the Sea" has just come to Palma de Mallorca via the CaixaForum, having travelled to various cities in Spain in larger or smaller version. The paintings and oil on board studies have been lent by the Sorolla Museum in Madrid. They reflect Joaquín Sorolla's passion for the sea, despite the fact he was not born at the coast. They also testify to his enormous skill in working en plein air, at great speed, trying to be faithful to the every-changing light, the restless sea in all its moods and the feel of the place in which he was painting.

Sorolla commented, "Me sería imposible pintar despacio al aire libre. No hay nada inmóvil en lo que nos rodea. El mar se riza a cada instante, la nube se deforma, al mudar de sitio – pero aunque todo estuviera petrificado y fijo, bastaría que se moviera el sol, lo que hace de continuo para dar diverso aspecto a las cosas. Hay que pintar de prisa porque cuanto se pierde, fugaz que no vuelve a encontrarse!”. Roughly translated, Sorolla said that it was impossible for him to paint slowly en plein air. Nothing stays still around us. The sea ripples continuously, clouds change their form as they move, and even if everything were totally still, even cast in stone, everything would still change in aspect because the sun moves all the time. You have to paint quickly because so much gets lost, some much is fleeting and will never return.

Any artist who has worked outdoors knows exactly what Sorolla was talking about.

The exhibition showed a fair number of oil on cardboard, small studies, "Colour Notes", and for me, they were the most fascinating aspects of seeing the show. In this first blog entry on Sorolla, I will concentrate on them, as far as I am able to find decent images. First of all, you see Sorolla responding to Nature's colours and forms and seeking the fleeting approximation of the colours and light that he saw. These small rectangles of colour impressions are so abstract it is amazing, even though Sorolla was a passionate Realist.

Since the sea is endlessly in motion, it is astonishing how Sorolla captures its moods and movement, particularly considering that he did not spend all his time at the coast. His early visits to the brilliantly-lit Mediterranean areas near Javea and Valencia were later contrasted with visits to the north at San Sebastian and Biarritz, with very different atmospheric and marine conditions.

The studies and paintings of the sea are, to me, the most wonderful part of Sorolla's opus. For him, of course, these studies were the preparation for the larger finished paintings. He knew that understanding a scene, preparation and prior choice of colours all helped when it came to working on a bigger canvas. He remarked, "The great difficulty with large canvases is that they should by right be painted as fast as a sketch. By speed only can you gain an appearance of fleeting effect. But to paint a three yard canvas with the same dispatch as one of ten inches is well-nigh impossible.”

Nonetheless, Sorolla also knew that once he got going, all bets were off on how the painting would evolve, because the light, scene, sea, would be continually changing. He advised, “Go to nature with no parti pris. You should not know what your picture is to look like until it is done. Just see the picture that is coming."

For him, as for every artist, especially one working en plein air, every work was a gamble. In his case, however, his gambles paid off handsomely most of the time.

A Matter of Timing /

I learned long ago, by hard experience, that when working en plein air, you need to be opportunistic and aware of what is happening around you. Somehow luck and timing often are part of the artistic process!

On a windswept hilltop overlooking wide Burgundy plateaux of ploughed fields and neat vineyards, I was deep into drawing a small goldpoint.Ii was trying to be mindful of Matisse's dictum: "one must always search for the desire of the line, where it wishes to enter or where to die away." That wisdom seems so appropriate when drawing in metalpoint, with the ability of the stylus to state its own terms about energetic moments and those when it fades away to a whisper.

I suddenly became aware of the roar of a mighty behemoth of a tractor approaching. I happened to be parked at the edge of a field of barley stubble, as I had become fascinated by the random patterns of the chaff and stubble half lying, half standing after the harvest. The tractor got closer and closer.

I was just trying to decide if I had finished the drawing or not when I glanced up. The monstrous machine was heading straight for my part of the field and the farmer atop his giant tractor was looking hard at me!

I hastily moved right out the way and waved my apologies to him. He nodded, lowered his plough, and before I could count to ten, my barley stubble was no more. Instead, rich russet soil was being churned up in powerful furrows, the first move in the every-renewing cycle of life in the farming world of cereal cultivation.

My timing was impeccable. There were no other fields left of cereal stubble visible anywhere. I had managed to find the last field to be ploughed. In essence, I had more than followed Matisse's idea of finding where the line wishes to enter or die away. The plough was the guiding factor! Or in other words, carpe diem works in art too!

Rules of the Plein Air Game /

It is always fascinating to realise how one evolves as an artist. I am constantly surprised at how things change, whilst the core impulses and responses remain consistent.

I was reminded of this yesterday as I found myself responding to the intricate beauty of ancient olive trees and mighty Mediterranean pines in a way that I would not have done a year or two ago.

Yes, I love trees, and have always found them of intense interest and delight. But now, with my eyes more attuned to their texture and patterning of wood and bark because of the way I am frequently drawing in metalpoint, I “see” differently. And more than that, I find myself learning more and more adapting and moving to a very selective mode of drawing en plein air.

There is an interesting passage in a book I read some time ago, Monet by Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, published by Abradale Press in 1989. Discussing painting (and by extension drawing) en plein air, “To paint directly, to follow the rules of the plein air game, means to start with what is given from a particular position. Studio painting avoids occlusion problems (i.e. one near form hiding another behind it), but plein air means you have to choose your position and you have to deal with being blinded by overlapping features.”

Where you chose to stand or sit, what details you pay attention to: these are critical decisions for the artist to make at the onset of a work of art. The passage in Monet gives the example of a view down a straight road.

It establishes the visible world in depth at the same time that it establishes the position of the observing eye. It defines the relationship between seer and the seen within a geometrically precise structure.

Every time now that I start a metalpoint drawing, I need to decide on my position – where I am going to sit. This determines the details that visually jump out at me amid the welter of detailed information on the patterned bark of a tree, for instance.

Those selections dictate the “geometrically precise structure”, the composition that I have in mind (although that tends to evolve as I work). It also means that I have to “prune away” details that will not fit nor strengthen the drawing towards which I am almost instinctively groping.

It is indeed ideally a rather instinctive, non-conscious-thinking mode that I hope to achieve because I find that is when the best drawing happens. Not always possible, alas!

These are some of the more recent choices I made whilst sitting in front of mighty trees as to where I sit and what details are thus predominant and visible.

The rules of the plein air game become paramount.