When John Singer Sargent painted this scene of Claude Monet working en plein air, he recorded the heyday of the Impressionists' love of working outdoors to record and celebrate nature. Ever since, there has been a long list of wonderful plein air artists on every continent, and we artists, living today, have a rich heritage of landscape art from which to be inspired. This is the final Part 5 of my blog entry on Plein Air Art- Looking Back.

Read MoreWinslow Homer

Painting the Atlantic Ocean /

I have been reading Simon Winchester's book on the Atlantic and found it interesting to read what he wrote about this mighty ocean being the subject of paintings. It started me thinking of paintings I have seen in museums which depict maritime scenes. Then, of course, there is the distinction to be made of where exactly is the body of water that each artist shows.

Think, for instance, of all the wonderful Impressionist painters' works showing the sea off the Normandy coast of France. Is one being purist in defining those maritime scenes as of the English Channel, rather than the Atlantic? Eugene Boudin with his base at Honfleur, Monet, Manet, Courbet, Pissarro, Sisley - they all gravitated to the Normandy coast from the 1860s onwards. Their paintings show the sea in its many moods - sparkling, like Monet's wonderful

Manneporte Etretat, February 1883, Claude Monet,

(Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Gustave Courbet studied the power of the waves at Etretat too, but his paintings show the darker moods of the sea. In 1869, he did two paintings of

The Wave, 1870, Gustave Courbet, (Image courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie)

There was, of course, endless experimentation amongst artists working on the French coast. By 1885, Seurat was treating the sea very differently. This is his English Channel at Grandcamp.

English Channel at Grandcamp, Georges Seurat, (Image courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, New York)

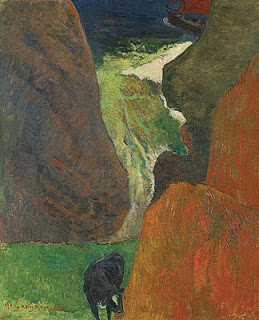

Gauguin perhaps painted the Atlantic more directly, during his stays in Brittany in the 1880s. Based in Pont Aven and at Le Pouldu, he painted feverishly, both looking to the green Breton lands and out to sea, the ever-changing Atlantic.

Seascape with cow/At the edge of the cliff, 1888, Paul Gauguin, (Image courtesy of the Musee d'Orsay, Paris)

Rochers au bord de la Mer, 1886, Paul Gauguin, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of Goteborgs Konstmuseum, Sweden)

However, earlier artists had depicted the sea, further north in what is perhaps even less the true Atlantic Ocean and more the North Sea. During the 17th century, when the Dutch were consolidating their mastery of the sea, their artists were celebrating the many moods of ocean and shore.

(‘Fishermen on Shore Hauling in their Nets,’ c.1640, Julius Porcellis, Oil on panel, 393-by-546mm, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK).

Willem van der Velde, both father and son, were also famed both in Holland and England, for their maritime scenes, in which naval engagements were often depicted. Both showed a knowledge of the Atlantic and the North Sea, but again, it is, I suspect, often hard to distinguish where the divide between Atlantic and adjacent waters exists in the art.

Three Ships in a Gale, W. van der Welde, 1673 (Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London)

Small Dutch Vessel close-hauled in a Strong Breeze. W. van der Velde, circa 1672. (Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London)

However, by the 18th century and the era of great voyages of exploration (think Captain James Cook on the HMS Endeavour, with Sidney Parkinson as the official artist on board during the 1768-71 voyage, or the much later, famous 1831-35 circumnavigation of the globe by the HMS Beagle, with Charles Darwin as naturalist and Augustus Earle as artist), maritime art had widened its scope. It was not just the Atlantic Ocean that was now well known, but the other great bodies of water around the globe.

Nonetheless, J.M.W. Turner, in some of his great sea paintings, looked back to Williem van der Velde the Younger. In his amazing use of light, gave the feeling of the ocean new and dazzling interpretations. In the painting of the Slave Ship, based on anti-slavery poetry,Turner depicted the slavers disposing of dead and dying slaves before an impending storm.

The Slave Ship, J.M.W. Tuner, oil on canvas, 1840, (Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

By the mid-19th century, many sailors knew first hand of the fury of hurricanes and typhoons. On the Western/American side of the North Atlantic, artists were also beginning to address marine painting. One of the first was Massachusetts-born Fitz Hugh Lane, (1804-1865), known as a Luminist painter and a most successful exponent of the Atlantic as seen from the New England coast.

Brace's Rock, Gloucester, MA, circa 1864, Fitz Hugh Lane (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington)

Other famed exponents of the Atlantic include Winslow Homer. His most acclaimed marine paintings date from the 1890s, when he was living some seventy-five feet from the water in Prout's Neck, Maine. Like so many artists, he was fascinated by the power of waves crashing on rugged coastlines.

Sunlight on the Coast, 1890, Winslow Homer (Image courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art)

Today, we artists have a wonderful heritage to which to refer when we think of paintings of the mighty Atlantic Ocean. There are countless artists working today along the coastlines of North and South America, Western Europe and Africa, for the power of the ocean summons us all.

Artists' Ways of Seeing Things /

I am reading a book entitled "Moonwalking with Einstein. The Art and Science of Remembering Everything" by Joshua Foer. The title is self-explanatory, the style is highly readable as Foer is a seasoned writer for such publications as the New York Times, National Geographic, Slate, etc. The content is totally fascinating - about how science is slowly understanding better how the human brain works, especially in terms of memory.

I still have many pages to go, but one page started me thinking about the parallels between artists and the master chess players that Foer was discussing. In the 1940s, Adriaan de Groot, a Dutch psychologist and chess player, decided to investigate what separated a good chess player from a master chess player - what was going on in their heads? Were the top players able to think further ahead in their moves, did they have better mental tools or a more honed intuition for the game? From past high level games,De Groot selected a series of board positions where there was one correct move to make which was not all that obvious. He then asked a group of top flight chess players to ponder these boards and to think aloud as they selected the proper move.

To De Groot's astonishment, the players mostly did not think many moves ahead, nor did they consider more possible moves. What they did was to see the right move, and almost immediately. After analysing the players' commentaries, De Groot realised that the chess experts were reacting, rather than thinking, and they could do this because their long experience of playing had taught them to think about "configurations of pieces like 'pawn structures' and immediately noticed things that were out of sorts, like exposed rooks". They had learned to see the whole chess board and thirty-two chess pieces as systems and groups. Later studies of top players' eye movements confirm that they literally see a different chess board, for they see more edges of the squares, which means they are encompassing whole areas at once. They also move their eyes across greater distances, without lingering for long at any one spot. Those places on which they do focus tend to be the key areas linked to making the right move.

This description of how master chess players function made me think of artists who have honed their skills day after day, year after year. Their eye-hand coordination has been perfected, their senses of composition/design, colour and content are developed. When they draw a nude, for instance, or work on a landscape painting plein air, for instance, they are not looking at just one spot. Rather, they are encompassing the whole so that almost intuitively, they can adjust their composition, their values and colour in the work for the best results. Their powers of observation and concentration are almost unthinking, because they are trained and disciplined.

The Red Canoe, 1889, watercolour, Winslow Home (Image courtesy of the Peabody Art Collection, Baltimore, Maryland)

To me, Winslow Homer is an example of a highly skilled painter, producing amazingly fresh landscapes, frequently plein air, and often in watercolour. One such example is "The Red Canoe" (image courtesy of the Peabody Collection, the Athenaeum).

Foer goes on to comment on the master chess players' amazing memories. I suspect that the great artists, past and present, also intrinsically rely on their memories quickly to understand a subject after a brief moment of studying it, Like the chess players, they can also call upon past experiences to bolster and inform their present work. The saying, "Been there, done that" applies, in a very positive sense, to an artist as well as chess players. Perhaps one should just add, "umpteen times"!

Artists' Expectations /

When an artist travels to somewhere new, or goes out on location to work plein air, there is always a sense of expectation. Is that good, or does it hinder one's reactions and inspirations?

I was reminded of this frequent conundrum when I read a statement made by photographer Michael Eastman in Ivy Cooper's interesting article, "From Drive-Ins to Palazzo in ARTnews, summer 2010 issue. Eastman is considering travelling to Japan, New Zealand and Antarctica for new photographic ventures. When he mentioned this, the obvious question to ask was what subject matter will he photograph. His reply really resonated with me. "I'm not sure what I'll find there.

I think the biggest risk to an artist is expectations. (My emphasis) Whatever your expectations are, they always get in the way. If I don't have expectations, if I hit the ground running, if I move forward and start looking, I'll see new things."

When I thought about Eastman's remarks, I realised how accurate he is. I have found, time and time again, that if I switch off my brain when I arrive somewhere, and just let my subconscious 'float' and my eyes wander all over, then suddenly, bang, there is something interesting. If, on the other hand, I have envisaged some scene or object ahead of time, expecting to find that it is what I want to draw or paint, I frequently feel flat and uninspired when I get there. Totally perverse, but there it is! Of course, if one is commissioned to do a specific thing or landscape, then that is another matter. Even so, I try to feel neutral, without any preconceived idea of how I am going to tackle the commission. At least, like that, new angles, new approaches, fresh concepts can all come to mind.

If one thinks of the wonderfully spontaneous watercolours,for instance, that John Singer Sargent did when he was travelling, I suspect that he did not burden himself ahead of time of too many expectations. He just had his painting equipment to hand and let his keen eye spot the opportunities.

Artist in the Simplon, c.1909 - John Singer Sargent (Image courtesy of Fogg Museum (Harvard Art Museums), Cambridge, MA, US

This watercolour, Artist in the Simplon shows just such an approach. Sargent was following in the footsteps of an earlier master of watercolours, Winslow Homer. He had pioneered the use of watercolours for spontaneous, fluid work that showed an opportunistic artist's eye. English "Cloud Shadows", painted in 1890, is an example of this).

Cloud Shadows, Winslow Homer, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of the Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art)

Artists Sketching in the White Mountains, Winslow Homer (Image courtesy of Portland Museum of Art)

Expectations, in most situations, tend to let one down. In art, they seem to dampen, even stifle, creativity. Spontaneity, openness and an observant eye seem to be good substitutes.