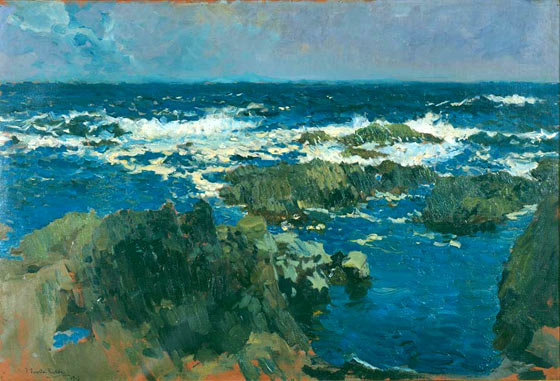

My last blog post was on Joaquín Sorolla's approach to plein air painting, after I saw the CaixaForum exhibition, "The Colour of the Sea" in Palma de Mallorca. His "Colour Notes" are so fresh and searching, so bold and gestural, that I sometimes felt that the resultant paintings, in which this carefully observed material was incorporated, lost a little in impact. Nonetheless, the exhibition shows beautifully how Sorolla, set up on the beach in very practical painting fashion, was ever-intent on capturing the endless changes of the seascapes. His meticulous studies of the different hues of blue, for instance, show his passion for capturing the limpid colours of the sea, the play of light on the waves or on bodies in the water, their diversity of tone. Yes, he was basing all his art on Nature, in a realistic fashion, but he certainly was breaking down what he saw into the most abstract of shapes and compositions.

Look, for instance, at the Young Swimmers. Their skin underwater becomes a shimmer of alabasters floating in this energy-filled abstraction of green ripples and dancing light.

Another canvas that interested me in the flattening of the perspective is Marie at the Beach. As in other paintings he did of contrejour light on cliff tops, Sorolla flattened out the distances: the sea below is virtually on the same plane as Maria, because one senses his total fascination with the sea and its restless play of light and foam.

The translucence of white fabric, seen contrajour against the sea, is another of his favourite subjects. Just out of the Sea demonstrates this marvellously; it is all about that luminous, undulating light blowing in the wind, contrasting with the glowing solidity of the mother and small boy, all rendered tangy in the salt air and the susurration of the turquoise sea.

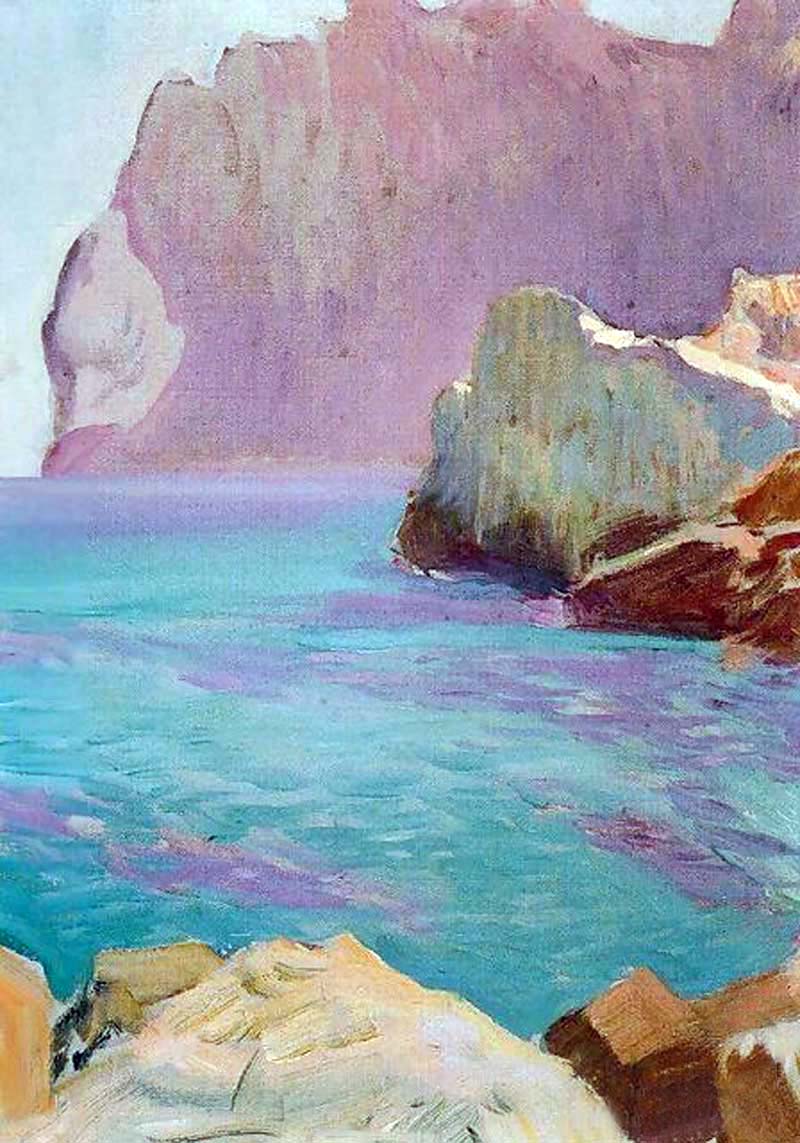

The marine landscapes are all about luminosity, distance being dissolved into pure colour. Sky and sea are his fascinations, his challenges. No wonder he stated, ""I could not paint at all if I had to paint slowly. Every effect is so transient, it must be rapidly painted.”

His 1919 works done at Cabo San Vincente in Mallorca are pure colour hymns. No wonder he is loved by so many for these celebrations of the sea, one of Spain's greatest beauties in his lifetime. We are lucky that he recorded his country's coastal scenes before they were transformed by 20th-century mass tourism.