As so often happens, no sooner had I posted my blog on "Lines" than I read about Pat Steir's latest exhibit at Sue Scott Gallery in New York that ended last month. Entitled The Nearly Endless Line, it was a roughly brushed line that wended its way around corners and out of sight in a room, only to reappear, sometimes looping and squiggling to take on a life of its own.

My thanks to the Sue Scott Gallery for the image of Steir's installation.

Sometime emphasised by a slightly darker second line, it stood out from walls painted a deep royal blue that apparently was incredibly densely painted. The other magical ingredient was light, mysterious and other worldly. The immersion in this space, following this line around the room, could signify the passage of time in an almost hallucinogenic setting. Pat Steir, well known for her waterfall, drippy paintings, has also been creating wall drawings and installations for a number of years - I wrote a little about her work when she was showing Pat Steir: Drawing out of Line at the Neuberger Museum in New York at the end of 2010.

The power of a simple line is fascinating, particularly when it is large-scale, against a resonating colour and with appropriate lighting. Steir did Another Nearly Endless Line at the Whitney last year as well - not as powerful as the one at Sue Scott, but still one conveying a questing, thoughtful message.

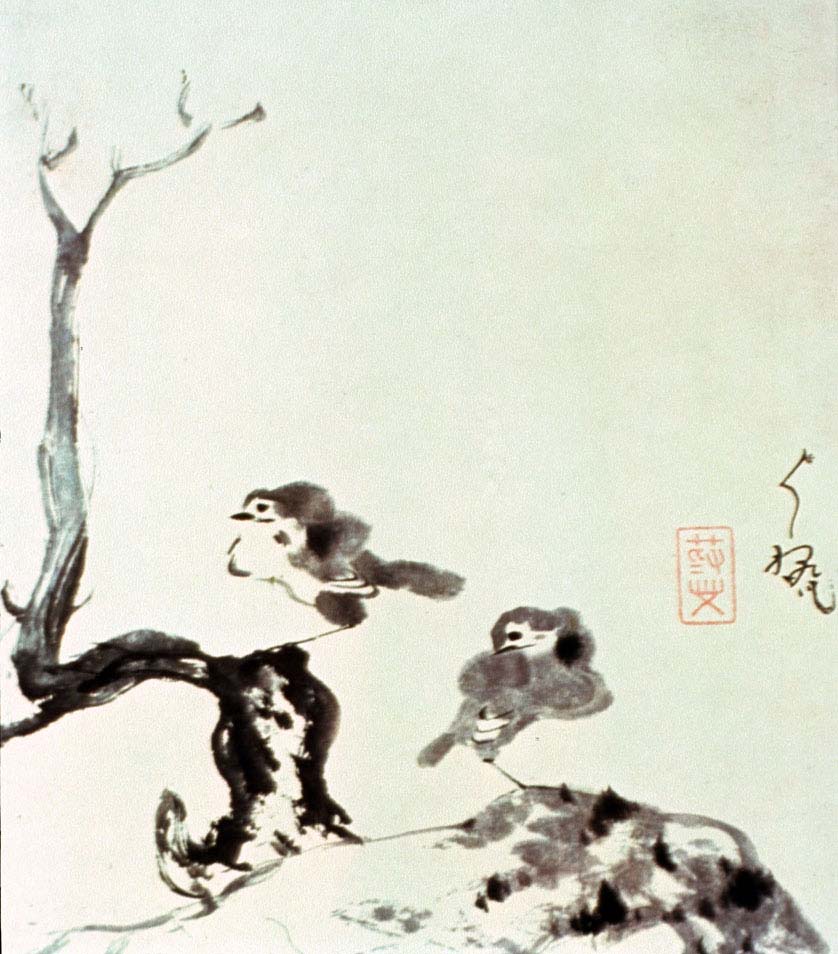

I can't help thinking too of the power of a single sumi-e ink brush stroke in Chinese or Japanese brush drawings. These marks of beautifully nuanced tone can be a symphony of simplicity, yet make such an impact.

Look at these questing lines of calligraphy, Daruma, by Japanese poet and calligrapher, Ota Nampo Shokusanjin (1749-1823).

Shokusanjin - Ota Nampo - Daruma

Two Birds, Bada Shanren, 1705

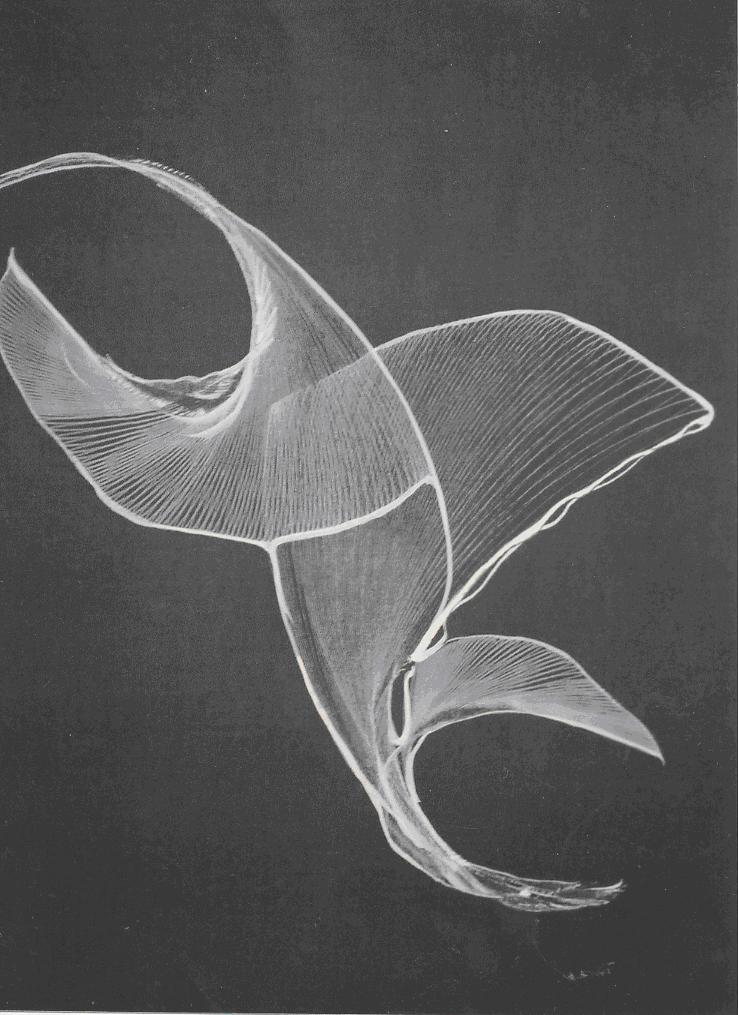

Hakuin Ekaku (January 19, 1686 - January 18, 1768) was one of the most influential figures in Japanese Zen Buddhism and one of the greatest Japanese Zen painters.

Blind Men crossing a Bridge, Hakuin Ekaku (1685–1768)

Death, Hakuin Ekaku

Each of these works rely on the same sureness of hand that modern draughtsmen and women need to achieve powerful lines, whether on paper, scrolls or walls. The implicit message in all these memorable works is - for an artist - practice, practice, practice. As well, of course, as inspiration.