When you think about it, life is full of lines. Power lines, phone lines, railway lines, the lines that define buildings and streets, cobwebs and even the veins of leaves. For an artist, however, using lines in drawings can give rise to many different philosophies and approaches.

For instance, Paul Klee famously and deliciously said, "A drawing is simply a line going for a walk". That statement goes along with his whimsy and imaginative approach to creating art. Just like his statement that "a line is a dot that went for a walk".

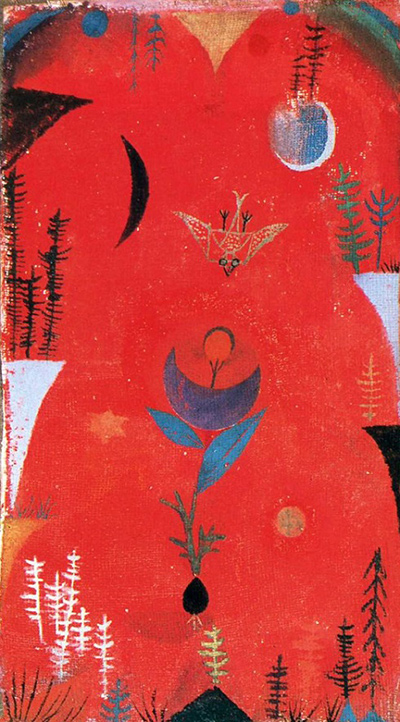

Paul Klee "Lines, Dots and Circles"

This is beautifully illustrated by one of his numerous drawings. It shows that whilst Klee was clearly drawing very intelligently, and often with deliberate wit and parody, particularly as the Nazis rose to power, nonetheless intuition and pure creativity flowed happily.

Another artist who allows the line simply to flow from her, without premeditation, is Christine Hiebert. Very widely exhibited and heralded for her inventive approach to drawing with media ranging from blue tape to charcoal, she investigates the nature and language of line. She starts a drawing on a blank wall empty of ideas, not using a pre-drawn sketch. She says, "The final outcome is always something I didn't anticipate. The process can be unsettling, but that is how I prefer to work. For me, drawing starts with the problem of the line, how to form it and how to follow it. In a way, it ends with the line too. The line remains independent, searching, never completely absorbed by the community of its fellows." (Except from her Davis Museum brochure for Reconnaissance, August 2009.)

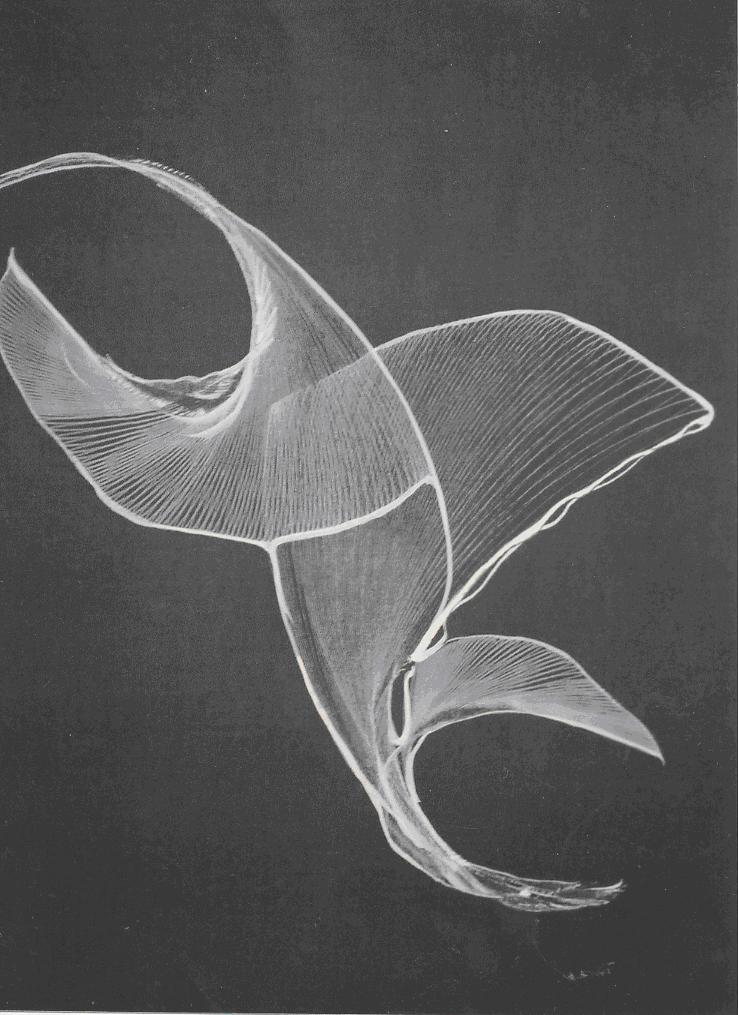

Untitled, charcoal and rabbit skin glue on paper, 2000, Christine Hiebert, (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

I find her approach of visual thinking through drawing fascinating, because there is also another, more traditional approach to drawing. That is based upon seeing or conceiving of an image which the artist then proceeds to translate, through line, into an permanent image. This has been an accepted way of creating line drawings in Western art since the monks began to delineate their illuminations on vellum and parchment and their heirs, during the Renaissance, brought the art of drawing to great heights. Not only were the lines then used to explore ideas and make studies in preparation for paintings, but the artists also made finished drawings, line after careful line. Indeed, for many centuries, skill in drawing was almost predicated on little erasure, in silverpoint (that permanent line won't budge!), but also in red chalk (the bravura medium), black chalk, pen and ink and even charcoal.

Today, many artists are pushing the definitions of using line or making drawings far beyond those traditional approaches. Perhaps it is only fitting in a world where man made lines - the power grids, the computer chips, or whatever - predominate.

Wiki.Picture by Drawing Machine 2

When a beautiful drawing can be produced by Drawing Machine 2, using a mathematical model, the lines indeed go for their walk. Paul Klee would certainly approve, I am sure. It is good to remember that any approach to lines is possible, as long as we artists allow ourselves to be creative and free. That is my definition of fun!