That perspicacious genius, Pablo Picasso, once said, about his art, "All I have ever made was made for the present, with the hope that it will always remain in the present."

His work has just been tested again from this point of view, with an exhibition, Picasso by Picasso, on show at Zurich's Kunsthaus, until the 30th January, 2011. This is a semi-repeat of an exhibition that Picasso himself selected in 1932; he chose 225 of his works from different periods and styles, and the show was very successful.

This time, one hundred of the original works selected have been reunited, and according to William Cook, writing in The Spectator on October 30th, 2010, the exhibition is again very successful. Since the works are all pre-1932, there is not the political element that appeared in Picasso's work after Guernica, and apparently, the works appear far more optimistic than later paintings. Most importantly, the exhibition passed the acid test of Picasso's work remaining relevant, present and with impact for today's viewers. In William Cook's words, the show still seems "bang up to date".

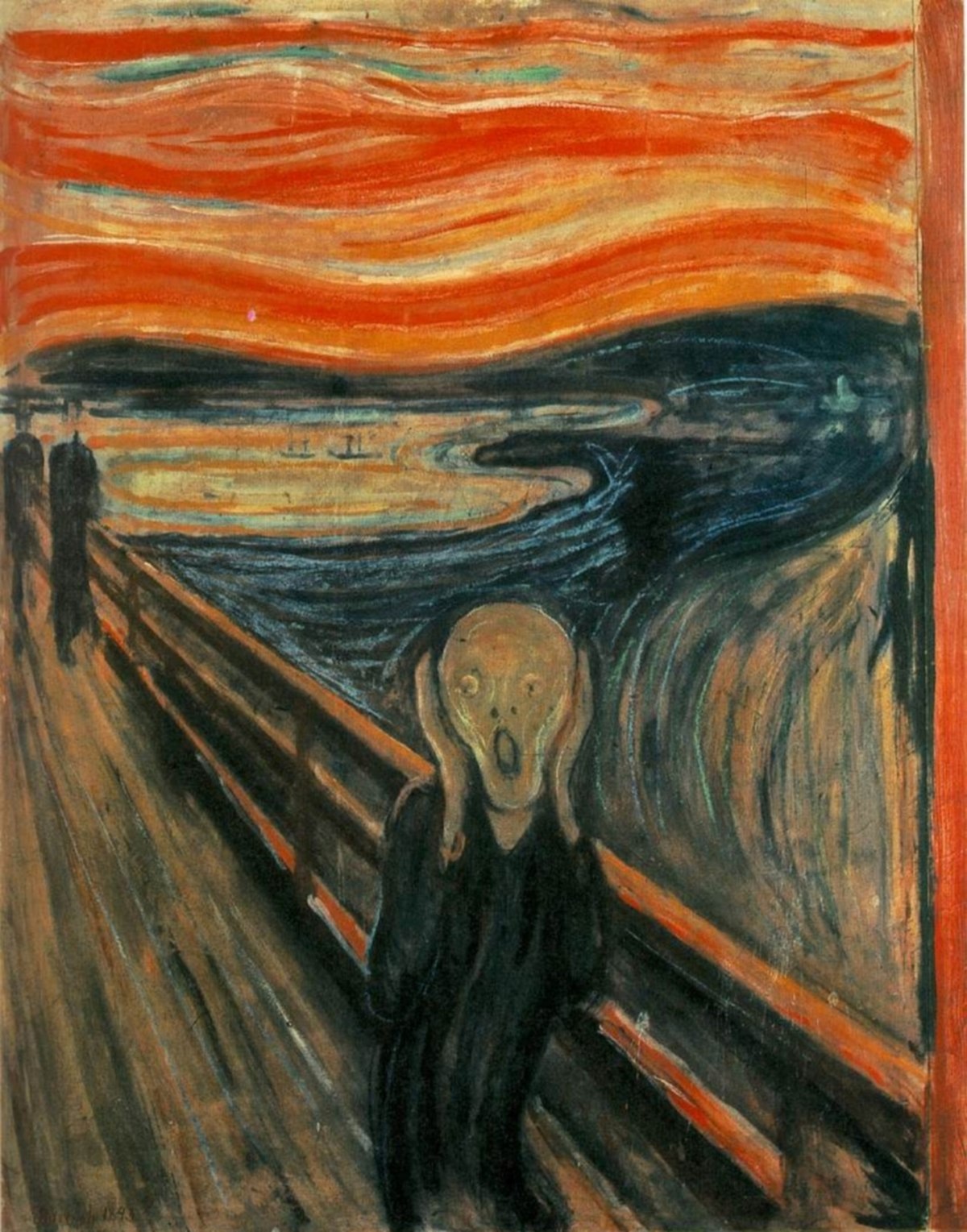

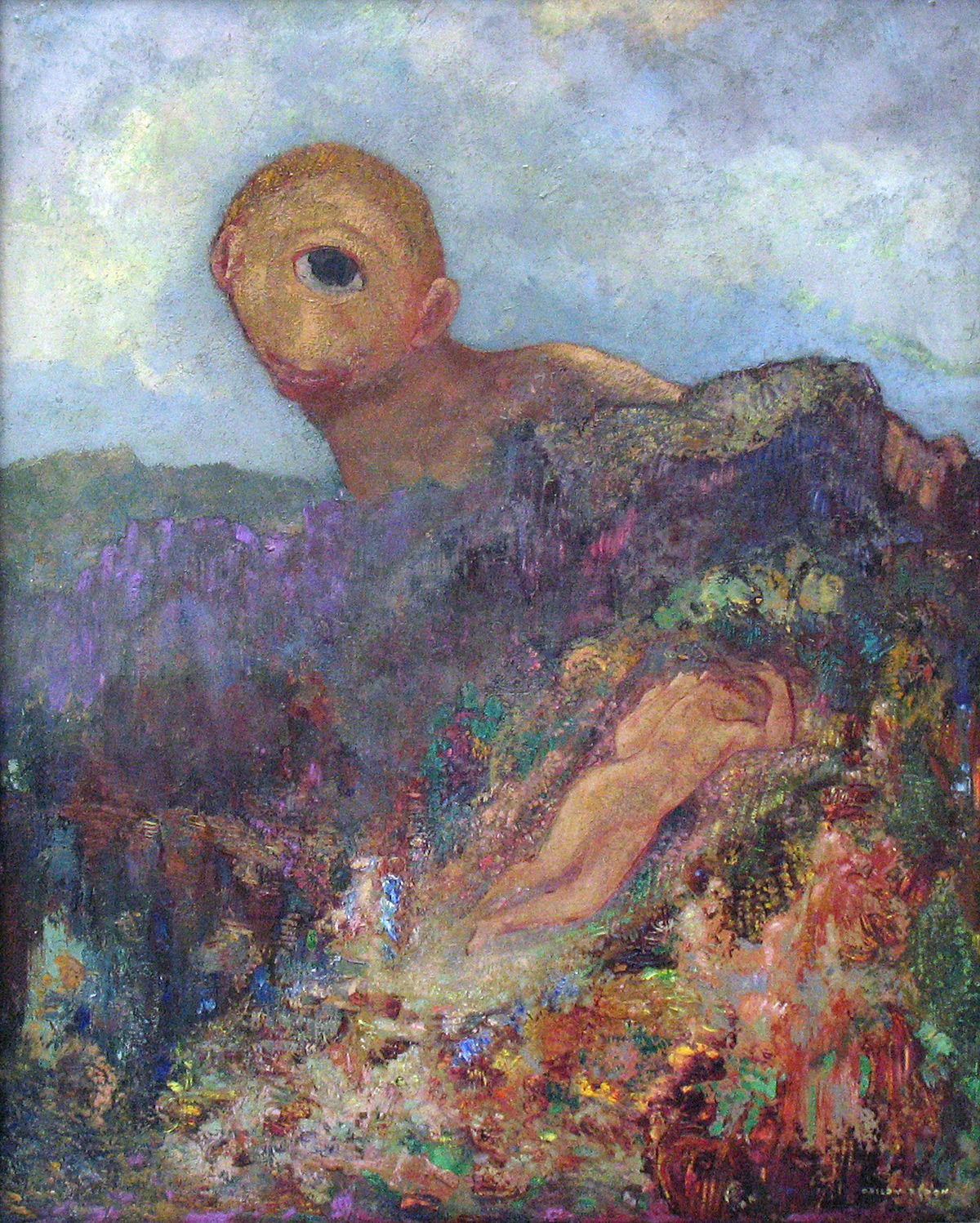

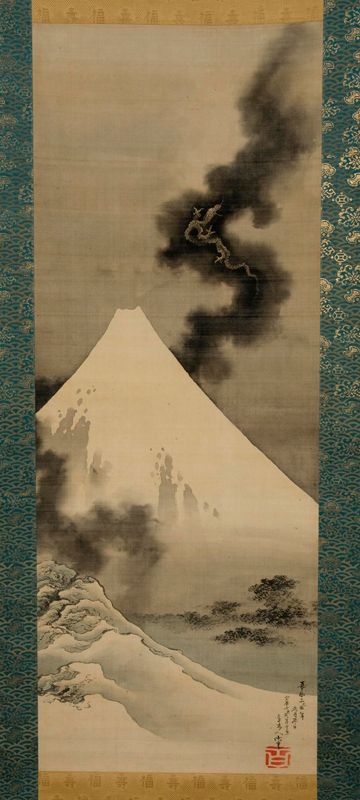

For art to remain in the present, what does it need? I am sure everyone has a different answer, but for me, it boils down to art that contains a passionate message about human values, aspirations, emotions... The great art that has come down to us from past centuries and from different cultures all touches a cord in us, reminding us of universal bonds. The art can tell us of people, places, plants and trees, animals - in stylised or realistic fashion - but there is always a depth of emotion in the overt or subliminal messages.

Think of a Rembrandt portrait with its psychological impact, such as this masterpiece from the Frick Collection