Inching my way back from the roles of hospital companion and guardian to my husband as he recovered from an emergency operation, I finally felt I could slip back into my artist world a little. It was a welcome move as there is nothing more debilitating, for patient and family, than sojourns in a hospital. My first treat to myself was to see a recently opened small exhibition at the Museu Fundacion Juan March in Palma de Mallorca. Entitled "Things: The Idea of Still life in Photography and Painting", it straddled 17th century Dutch still life paintings and late nineteenth-early twentieth century photographs.

It was a really interesting premise, examining the forms of still life and even the cultural differences in the use of the word, "still life". The German and English versions of the words echo the original Dutch/Flemish concept of examples of things that are faithfully recorded in a carefully organised composition. But the Spanish "naturaleza muerta" or 'bodegon" stray far from the original premise. Most of the work presented represented northern artists, thus closer to the true sense of still life.

The Dutch paintings were lovely small ones, where the artists had delighted in the play of light on a glass goblet or a small ceramic dish, spoon or the crisp glint of a peeled lemon.

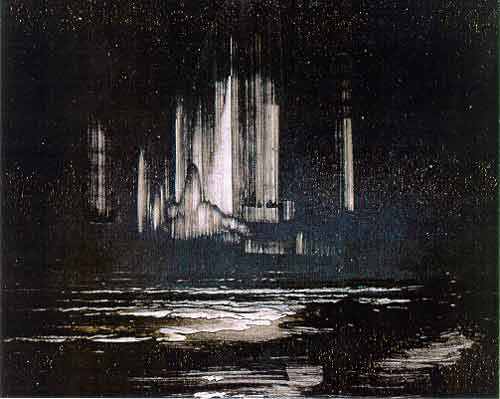

The leap to the early medium of photograph to record still life that, mostly, was pre-composed, was interesting. Sometimes, the photographs seemed airless, compared to the paintings, still a characteristic of many photographs today when compared to paintings. Yet there was an elegance and refinement in the photographs that were distinctive. As always, I seem to prefer the very simple compositions - such as one by Baron Adolphe de Meyer taken in 1908 of two hydrangea flowers in a glass of water, the reflections of the glass playing out on the wide expanse of the surface in the lower third of the photogravure.

The selection of photographic still life works was wide-ranging - from daguerreotypes to a coloured autochrome coloured back-lit plate of flowers by the Lumiere Brothers done in 1908, a circa 1895 trichromatic print of flowers (so much for all our modern "inventions" of technicolour) and then into the more modernist 1920-60 black and white work by Man Ray, Walker Evans, and many other European photographers.

Every interpretation of still life was there one could imagine - from carefully set up compositions, to views of life made still in abattoirs or after a volcanic eruption to Walker Evans spotting a natural still life scene on a back porch of a (sharecropper?) weather-beaten clapboard house.

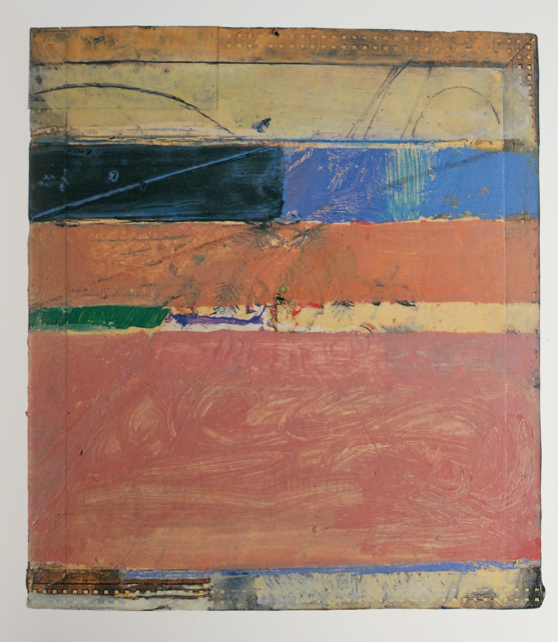

As I looked at the different compositions and the elements that made up those compositions, mainly derived from nature, I could not help realising that most of my current artwork is, de facto, still life. I am using elements of nature in compositions that record stones, bark, flowers --stilled by being placed in a setting other than their original one. I have only strayed a little, like many other artists, from the path of still life "inventor" artists of the seventeenth century by cropping, zooming in on some elements and eliminating others, framing and thus altering the original concept and layout of the still life set up.

I love feeling this sense of kinship and heritage that comes when you look at artwork from previous times and understand how and why you do things the way you do, thanks to those earlier artists.