I am always surprised by the sudden shock of rounding a corner in a busy airport and finding a moment of centering peace. It does not happen often, but when it does, it makes the travelling more bearable in today's abrasive airports.

It happened recently to me again. Atlanta's relentlessly busy, noisy airport had offered a few moments of quiet amid the pounding feet, with an exhibition of children's art on the walls of the international flight concourse E. The voices of these paintings sang of hope and joy, a contrast to the often intent and stressed faces of fellow travellers.

The really lovely moments of peace from art came in Madrid, an airport which has grown organically and offers many versions of art from different building phases of the airport. Even ceilings are well designed, as shown in Perec's lovely photo taken in Terminal 4 that opens this blog post.

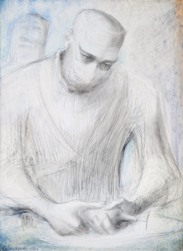

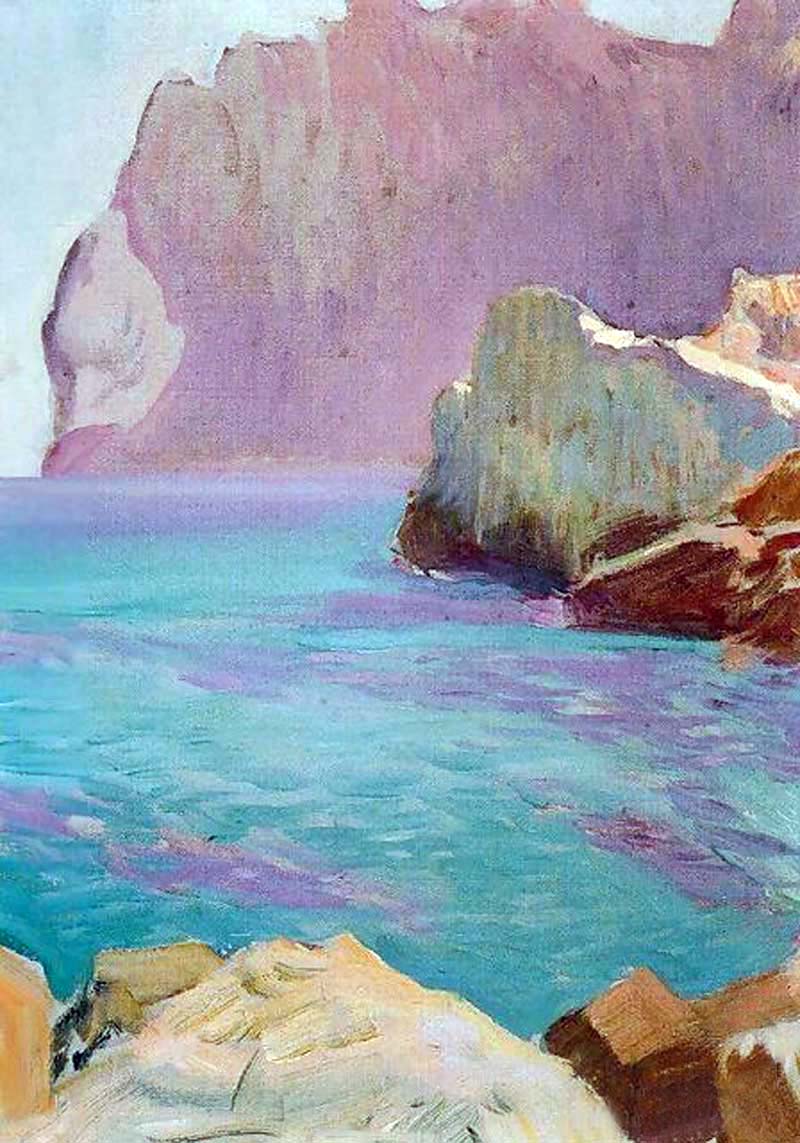

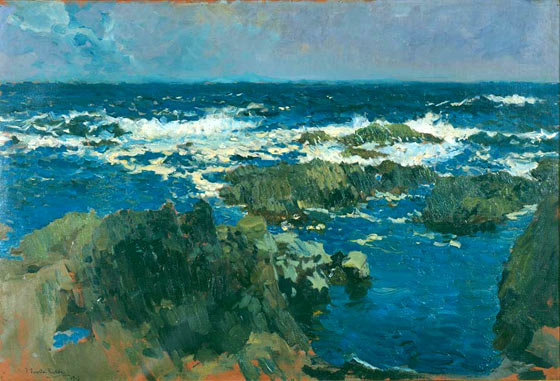

One huge merit of the airport is that there are no public announcements and the universal quiet is already a balm. Add to that the art, especially in some of the VIP lounges. It is quietly elegant in voice. You turn a corner and there is a collection of modern prints, discreet and well presented. Their effect stills and composes. You suddenly find the energy to go on with your trip, renewed in some subtle, indefinable way.

As you press on to the gate for your next flight, little prayers of thanks to those artists float up to the skies. Art - of so many different descriptions - fills our lives with richness and healing. It gives me hope for safe landings.