Everyone uses the word. Everyone feels that intuitively, they know what "creativity" means. Everyone also knows that it is a highly desirable quality to possess. Yet the definition of creativity is not so easy. The Oxford English Dictionary succinctly puts it as "The use of imagination or original ideas to create something; inventiveness." Wikipedia gets broader in concepts: "' the production of novel, useful products' (Mumford, 2003, p. 110). Creativity can also be defined 'as the process of producing something that is both original and worthwhile' or 'characterized by originality and expressiveness and imaginative'." The article goes on to add that there are countless other versions of definitions.

Of course, in the art arena, creativity is deemed indispensable if the artist is in any way to be successful. Yet, as we all know, there are so many versions of artistic expression that most are considered creative only by a few viewers. Only the truly exceptional are heralded by most people, and until very recently, the culture of each country also played a part in the degree of appreciation of the work created.

What set me off thinking about the concept of creativity was a wonderful expression I read in a marvellous new book, "The Churchill Factor" by Boris Johnson (Mayor of London Boris Johnson). Discussing Winston Churchill's amazing abilities, particularly in the World War II period, Johnson says, "he (Churchill) also had the zigzag streak of lightning in the brain that makes for creativity."

It is so often just that aspect, the "zigzag streak of lightning in the brain", that allows for unorthodox approaches, solutions that come out of left field, images configured in a wholly novel way, vivid writing that none else has achieved.

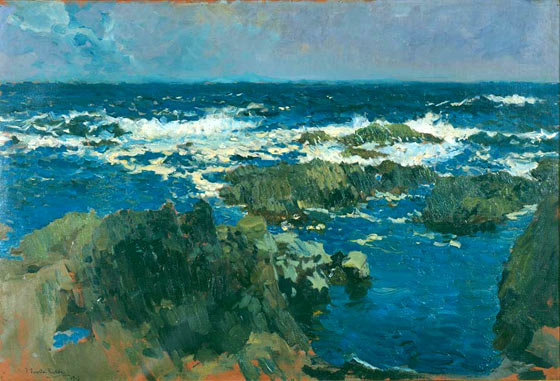

In art, for instance, every generation has had truly creative people who have broken out of the mould and done things differently. The Renaissance was full of artists - think, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Durer, Titian - developing linear perspective, depicting landscape in naturalistic fashion, executing portraits of people in realistic fashion, modelling with light and shade. Later generations perfected oil painting, shifted the focus of Western art to Mannerism - such as Tintoretto or El Greco. Then the Baroque artists flourished, like Caraveggio, Rubens or Rembrandt, and on the artists marched. Look at some samples of the different ways artists worked down the centuries.

By the 19th century, art needed some more innovatively creative artists and the Impressionists came to the fore, with Manet, Monet, Renoir and Pissarro leading the way. Creativity certainly flourished with Gauguin, Van Gogh and Cezanne, as they laid the groundwork for 20th century artists to find entirely new paths to follow in creating art in tune with their tumultuous century.

Perhaps another aspect of creativity as it zigzags through the human brain is that it very often has, as a springboard, the social and cultural context of the time. To me, creativity is partly a spontaneous phenomenon arising in some wonderfully imaginative human mind, but it is also like a seed that has been planted in soil fertile and well watered enough for the seed to germinate, grow and flourish so that others see and appreciate it.

Only when Churchill was at the helm during World War II could his multifaceted creativity flower so successfully as he led his country out of peril and to victory in 1945. In the artistic world, the Leonardo da Vincis, Titians or El Grecos needed the powerful patrons of the land and Church to enable to give successful expression to their creative skills.

Later artists have had a harder time finding patrons and supporters to allow them to create and to live decently, a situation known to most artists at one point or another. And does creativity flourish as fully and successfully when the artist is worrying about the next meal or the next rent payment? In every field, from art to architecture to engineering or technology, the same considerations pertain - how to ensure the optimum conditions so that human creativity can flourish. In truth, our collective future depends in large part on that zigzag flash of creativity in the human brain.