Every time I return to Portugal, I find I fall in love all over again with the azulejos, the glazed tiles that are the quintessence of Portuguese wall coverings, on the outside of buildings, inside churches, monasteries, even private houses, everywhere.

The beginnings of this wonderful art form date from over five centuries ago, when the Moors held sway in the Iberian Peninsula.In fact, the word azulejos comes from the Arabic word for “polished stone”, zillege,and the early types of tile - floral, geometrical, curvilinear in patterns - were introduced by them.Soon the Mozarabic centre of tile making was Seville, and for a time, Portugal imported tiles after King Manuel I visited the Seville factory in 1503.The Spanish adopted the Arab love of filling space and patterning everything.

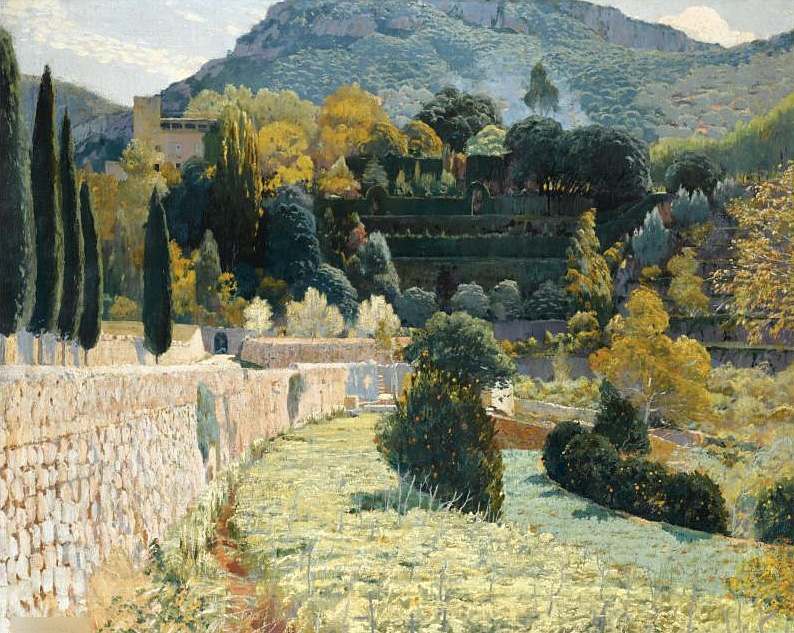

Early 16thcentury Seville tiles,Evora Museum, Evora

Later in the 16th century, the Portuguese learned how to make the tiles themselves after they had captured Ceuta in 1415, and after an influx of Flemish, Spanish and Italians brought their pottery skills to Portugal. (Their arrival is a reminder of how skilled workers flow around the world to where there is wealth and thus work; it is not just a phenomenon of our times!) The heyday of azulejos began and soon churches were adorned in amazing friezes and vast picture panels in “Delft blue”, palaces were tiled from top to bottom, stairways became glowing glories, the facades of buildings were works of art beyond belief. Wherever one goes in Portugal, there is beauty and complexity, thanks to the azulejos.

Just a few examples of tiled interiors that I have delighted in recently, in Evora and in a lovely small restored 16th century church in Redondo, both in the Alentejo region, inland and east of Lisbon.

If you are in Lisbon, one of the most fascinating and delightful museums to visit is the National Azulejos Museum. Spend all day there if you can – you will be rewarded. And elsewhere in Portugal, don’t forget to slip into every church or historic building you see, because there will be great beauty to reward you, thanks to the azulejos.