During my stay at DRAWinternational in Caylus, France, I found myself with the eternal conundrum – to work en plein air or to work in the studio. Partly, in truth, the colder weather made the choice a bit easier, but nonetheless, I was constantly aware of the tug of war internally, for I love to be out in natural surroundings to try and create art.

The other side of the equation is that in the studio, conditions for working are more organized and it is easier, physically, to work, particularly in metalpoint, which tends to be slower and more demanding of time and energies.

However, at the back of my head was a quote that I had read about Monet. He wrote, “All ‘motifs’ are mirrors – or else the project of plein airisme is as shallow as Baudelaire had once argued. The painter’s transactions with the ‘motif’ have as many dimensions as his sense of self and of his place in the world.” ("Motifs" are subjects and themes in a work of art.)

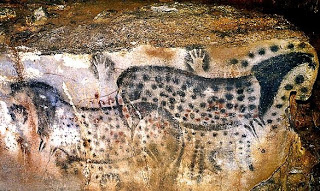

It is true that one brings to any artwork a sense of what matters, in most cases at least, and I think that when the work is done outside, perhaps the additional, often subliminal, messages are just as important. Man’s “communion” with natural surroundings underpins everything, whether or not today, we realize it.In general, ignoring nature imperils us in so many ways, as we keep finding out.

For an artist, in particular, the web and waft of nature informs every gesture, every impetus, consciously or not. Thus when an artist works outdoors, there are so many complex and often enriching issues that influence the execution of a piece of art.

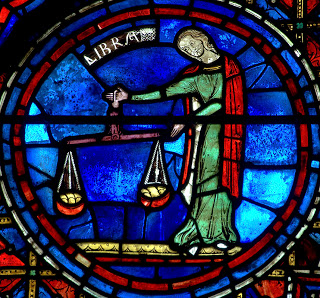

The other challenge is of course that there are indeed all those other considerations. An artist has to make choices, sometimes quick choices as light changes, or the scene disappears, or whatever. How to distill what one is trying to say, how to select the most simple and hopefully impactful aspects, how to mediate between a considered, controlled choice and a much more spontaneous, perhaps less “finished” piece of art, especially a drawing. Those are other aspects of plein air work. Each of these choices means that the work becomes a mirror of that artist, his or her sense of place in the world and self-definition.

I came across a lovely example of these simple artistic choices: last autumn at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, a wonderful place, there was an exhibition of silverpoint drawings that the American artist, Marsden Hartley, did.

He travelled in the 1930s to the Bavarian Alps and there, he drew a series of silverpoint studies that captured the spare geometries of these mountains. Very simple, very direct work – Hartley was communing with those mountain landscapes.

Travelling south from Hamburg to Garmisch-Partenkirchen,in the Bavarian Alps, Hartley apparently produced 21 of these spare distillations of the mountains.

Hills by the Lake, #2, silverpoint on paper, 11 x 15 inches, Marsden Hartley (Image courtesy of the Ownings Gallery)

Marsden Hartley produced a body of work that validates Monet's observation about "motifs" or subjects being mirrors of the artist.