There was a wonderful quote at the bottom of an art site that I saw recently: "The essence of all beautiful art, all great art, is gratitude." The wise man who said this was Friedrich Nietzsche, author and originator of countless bons mots.

It is true. Think of how you feel as you come out of a wonderful art gallery or museum, where you have feasted your eyes on wonders and stretched your mind in new directions.

When you encounter a portrait or a self portrait of someone who inspires and humbles, it makes one grateful. Take Rembrandt, for example, with his unflinching self-portraits, that tell one of life's experiences, the highs and the lows. They give one perspective for one's own life.

Self-Portrait, 1669. Rembrandt van Rijn's last self-portrait (Image courtesy of the National Gallery, London)

I am always delighted when one feels a connection to past artists, a sense that there is a marvellous heritage to inspire one's own artistic endeavours. As a silverpoint artist, I love it that Rogier van der Weyden recorded Saint Luke drawing the Virgin in silverpoint.

Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin, c. 1435–40, Rogier van der Weyden (Image courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

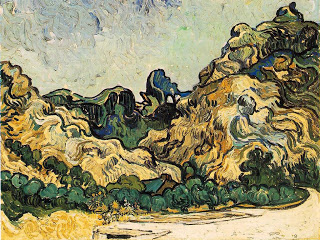

Think of the way Paul Cézanne can take one to expansive, simplified yet oh so powerful places, thanks to his obsessive staring as he painted his beloved landscapes around Aix-en-Provence. His watercolours of Mont Sainte-Victoire take one to magical worlds.

Château Noir devant la montagne Sainte-Victoire 1890-1895, Paul Cézanne ,watercolour, and pencil on white paper, (Image courtesy of Albertina, Vienna)

Nietzsche was right about the gratitude. He also remarked, "Art is the proper task of life".

Definitely a coherent man in his thoughts about art and artists.