After a long hiatus in posting because of family health concerns, it is good to start thinking a little about art and the art world. For me, art spells energies, health, healing and fascinations, together with beauty, stimulation and amazements.

There are always sparks of interest that one discovers when one can slip back through the doors into the art world. I love these tiny sparkles - they somehow help explain the bigger picture, often in an indefinable way.

My first discovery for the New Year - and a belated Happy New Year to all who read this - came during a visit to Savannah's Telfair Museums' current exhibition, Offerings of the Angels: Treasures from the Uffizi Gallery.It is a show which comes across as a rather thin selection of storeroom religious paintings, but, as always, there are interesting aspects. The most fascinating was a small painting on copper by Alessandro Tiarini (1577-1668, Bologna).

The Nativity, oil on copper, 1650s, Tiarini, 13 x 16.8 inches

I rounded a corner in the exhibition, and to my fascination, found another work that was painted on an entirely different surface, slate.

Christ Carrying the Cross, S.Del Piombo , 1535-1540 Oil on slate, 118 x 157 cm, Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest, Hungary)

Often, the artists who followed Piombo's example used the natural darks of the stone for their darks, thus eliminating the need for preparatory layers. In the Uffizi exhibit, there was another example of this: Alessandro Turchi (known as L'Obetto, 1578-1649) used dramatic chiaroscuro effects in his "Christ in Limbo", ca. 1620, which was painted on gleaming hard black jasper. Sometimes he also used black marble in the same fashion.

The alternative surface Piombo experimented with, copper, was already in use for etchings and engravings. Copper plates come in small sizes, and have the great advantages of ensuring there are no cracks, or craquelure, in the oil paint, as well as the ability to paint in minute detail. It has proven a very stable and long-lasting support for painting. By the end of the 16th century, Dutch landscape painters in Rome had adopted this support enthusiastically, and the use spread via Italians to other cities, such as Bologna. Already this form of painting had been shared with their Northern compatriots in the Netherlands and Flanders. Jan Breughel I painted a lot on copper, as did Peter Gysels, Osias Beert I, Frans Snyder, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Joachim Wtewael and Jan van Kessel amongst others.

Jan Brueghel I, "View of a City and River", Oil on Copper, 1578.

Jan Brueghel I, "Restbreak while Escaping Egypt", Oil on Copper

Jan Brueghel I, Still Life, Oil on Copper

Osias Beert I, "Still Life of Oysters, Sweetmeats, and Dried Fruit", Oil on Copper, 1609

he Golden Age, 1605, Jaochim Wtewael (1566–1638), oil on copper, Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum

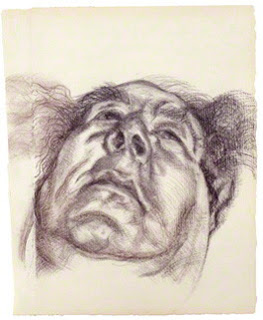

The Dutch were marvellous exponents of oil on copper paintings, especially in their heyday. Even Rembrandt tried his hand at painting on copper when he was in his early twenties; this is a recently re-discovered painting by him.

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669) Rembrandt Laughing. Oil on copper, about 1628. 8 3/4 x 6 3/4 in private Collection.

Later, another wonderful still life painter, Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, tried his hand at painting on copper.

Chardin, Fast-Day Meal, 1731, Musee du Louvre (France) Oil on copper, Height: 33 cm (12.99 in.), Width: 41 cm (16.14 in.)

Many other artists have painted works on copper, from El Greco (the "Adoration of the Shepherds", 1572-74) to Juan Sanchez Cotán, the famed 17th century Spanish painter of still life, who tried this small religious painting (acquired by the San Diego Museum of Art in 1990).

Saint Sebastian, oil on copper painting by Juan Sánchez Cotán, after 1603

My New Year discovery has given me delight and led me back to art that I have loved over the years when I stumbled upon such works in divers museum exhibitions. Jan van Kessel is one of the artists whose work on copper has most enchanted me. See what you think.

Butterflies and other Insects, 1661, oil on copper, 19.1 x 28.9 cm. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum

Butterflies and other Insects, 1661, oil on copper, 19.1 x 28.9 cm. Courtesy of the Fitzwilliam Museum

Jan van Kessel, Drawings of insects, c. 1653, Oil on Copper

Jan van Kessel, Drawings of insects, c. 1653, Oil on Copper

I have been looking to the past for works of art on copper. Perhaps it is also part of the New Year discoveries to explore the beautiful art that is being created on copper today. Even the trade group, the Copper Development Association, has interesting pages on such art-making. Happy exploring!