I have been reading Simon Winchester's book on the Atlantic and found it interesting to read what he wrote about this mighty ocean being the subject of paintings. It started me thinking of paintings I have seen in museums which depict maritime scenes. Then, of course, there is the distinction to be made of where exactly is the body of water that each artist shows.

Think, for instance, of all the wonderful Impressionist painters' works showing the sea off the Normandy coast of France. Is one being purist in defining those maritime scenes as of the English Channel, rather than the Atlantic? Eugene Boudin with his base at Honfleur, Monet, Manet, Courbet, Pissarro, Sisley - they all gravitated to the Normandy coast from the 1860s onwards. Their paintings show the sea in its many moods - sparkling, like Monet's wonderful

Manneporte Etretat, February 1883, Claude Monet,

(Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Gustave Courbet studied the power of the waves at Etretat too, but his paintings show the darker moods of the sea. In 1869, he did two paintings of

The Wave, 1870, Gustave Courbet, (Image courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie)

There was, of course, endless experimentation amongst artists working on the French coast. By 1885, Seurat was treating the sea very differently. This is his English Channel at Grandcamp.

English Channel at Grandcamp, Georges Seurat, (Image courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, New York)

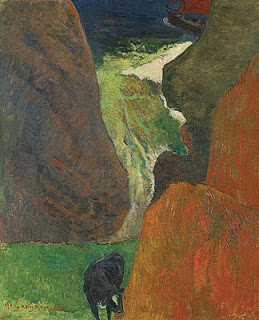

Gauguin perhaps painted the Atlantic more directly, during his stays in Brittany in the 1880s. Based in Pont Aven and at Le Pouldu, he painted feverishly, both looking to the green Breton lands and out to sea, the ever-changing Atlantic.

Seascape with cow/At the edge of the cliff, 1888, Paul Gauguin, (Image courtesy of the Musee d'Orsay, Paris)

Rochers au bord de la Mer, 1886, Paul Gauguin, oil on canvas, (Image courtesy of Goteborgs Konstmuseum, Sweden)

However, earlier artists had depicted the sea, further north in what is perhaps even less the true Atlantic Ocean and more the North Sea. During the 17th century, when the Dutch were consolidating their mastery of the sea, their artists were celebrating the many moods of ocean and shore.

(‘Fishermen on Shore Hauling in their Nets,’ c.1640, Julius Porcellis, Oil on panel, 393-by-546mm, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK).

Willem van der Velde, both father and son, were also famed both in Holland and England, for their maritime scenes, in which naval engagements were often depicted. Both showed a knowledge of the Atlantic and the North Sea, but again, it is, I suspect, often hard to distinguish where the divide between Atlantic and adjacent waters exists in the art.

Three Ships in a Gale, W. van der Welde, 1673 (Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London)

Small Dutch Vessel close-hauled in a Strong Breeze. W. van der Velde, circa 1672. (Image courtesy of The National Gallery, London)

However, by the 18th century and the era of great voyages of exploration (think Captain James Cook on the HMS Endeavour, with Sidney Parkinson as the official artist on board during the 1768-71 voyage, or the much later, famous 1831-35 circumnavigation of the globe by the HMS Beagle, with Charles Darwin as naturalist and Augustus Earle as artist), maritime art had widened its scope. It was not just the Atlantic Ocean that was now well known, but the other great bodies of water around the globe.

Nonetheless, J.M.W. Turner, in some of his great sea paintings, looked back to Williem van der Velde the Younger. In his amazing use of light, gave the feeling of the ocean new and dazzling interpretations. In the painting of the Slave Ship, based on anti-slavery poetry,Turner depicted the slavers disposing of dead and dying slaves before an impending storm.

The Slave Ship, J.M.W. Tuner, oil on canvas, 1840, (Image courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

By the mid-19th century, many sailors knew first hand of the fury of hurricanes and typhoons. On the Western/American side of the North Atlantic, artists were also beginning to address marine painting. One of the first was Massachusetts-born Fitz Hugh Lane, (1804-1865), known as a Luminist painter and a most successful exponent of the Atlantic as seen from the New England coast.

Brace's Rock, Gloucester, MA, circa 1864, Fitz Hugh Lane (Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington)

Other famed exponents of the Atlantic include Winslow Homer. His most acclaimed marine paintings date from the 1890s, when he was living some seventy-five feet from the water in Prout's Neck, Maine. Like so many artists, he was fascinated by the power of waves crashing on rugged coastlines.

Sunlight on the Coast, 1890, Winslow Homer (Image courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art)

Today, we artists have a wonderful heritage to which to refer when we think of paintings of the mighty Atlantic Ocean. There are countless artists working today along the coastlines of North and South America, Western Europe and Africa, for the power of the ocean summons us all.