I have been thinking about all kinds of beauty recently because I have just finished the most delightful book, "Wesley the Owl". It is not about art. It is the story of a young biologist, Stacey O'Brien working at Caltech who adopts a four-day-old owlet, a barn owl, who cannot be released into the wild. The next nearly two decades of her life are totally entwined with his.

Not only is a wonderfully moving account of this highly intelligent, fascinating creature, but it is also very much a book written by an observant, thoughtful scientist. The beauty of this barn owl's appearance, the beauty of the relationship with Stacey and the elegance too of scientific rigour and observations - all these are other facets of beauty that delight the senses and enrich a reader of this book.

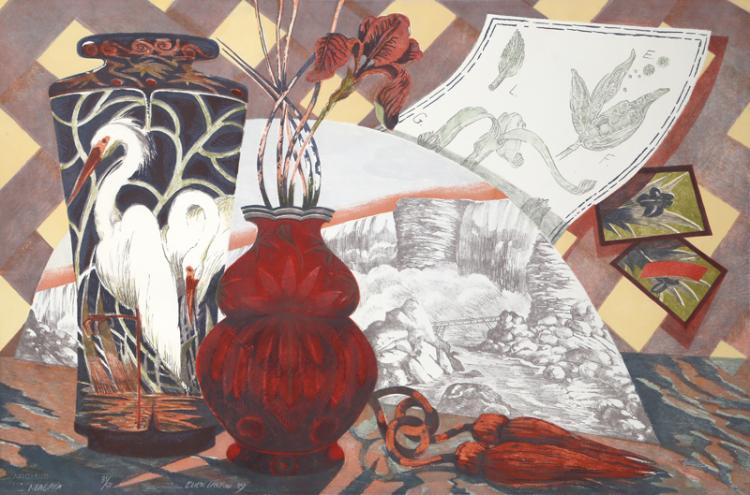

Barn Owl

Somehow the magic of such creatures, as we learn more about their marvellous attributes, feeds into making art and celebrating life in different creative ventures. Perhaps it is all about being passionate about life in general. Certainly "Wesley the Owl" is one of those books that helps make life sparkle. Do yourself a favour and read it if you have not already done so.