It is interesting how a beautiful place like Sapelo Island inspires one to do so many different types of art. Now that I have been able to look again at the work I produced last weekend on the Island as Artist-in-Residence, I realise that I managed to produce some very different pieces, ranging all over the place in subject matter and in approach.

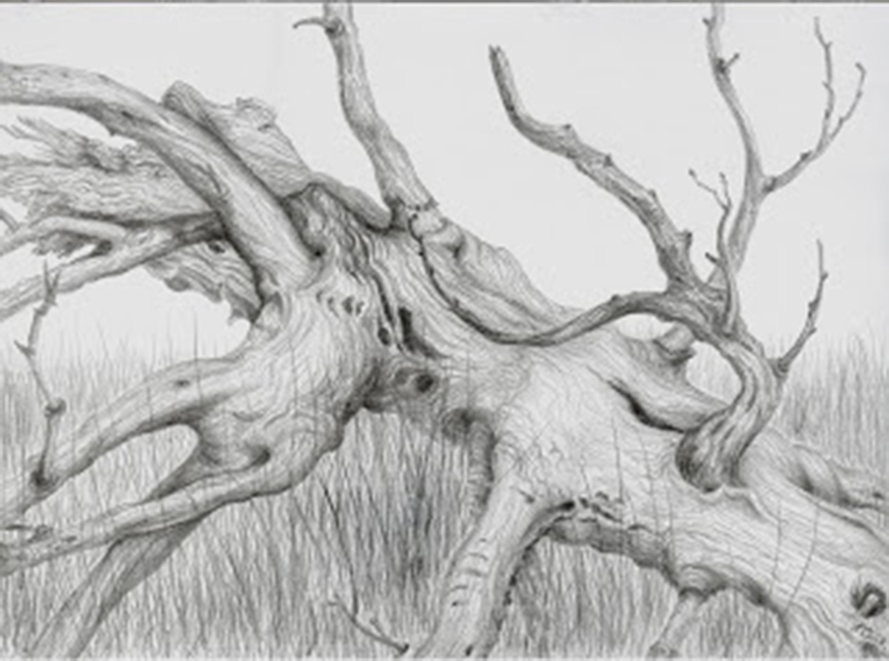

Long after the Storm, silverpoint, Jeannine Cook artist

It reminds me how one responds to places and situations in such varied ways. There seems, certainly in my case, to be some unspoken dialogue that goes on subliminally between what one's eyes are seeing and what one instinctively senses could become a drawing or a painting. It is almost beyond cogent thought. You just "know" that that will be a subject worth trying to tackle. It usually ends up humbling one, resulting in a somewhat different result that one visualised... in essence, the subject dictates the whole process. Scouting for possible subject matter is always initially instinctive. Only after one has decided that there is something there to be explored does one try to analyse what exact medium to use and how to go about actually physically doing the artwork. Often this whole process is rapid, because when working plein air, you know that the whole thing is fleeting. Light will change, the tide will alter, the birds will fly off, people might come along to fill the empty scene or whatever.

In any case, I found so many things of fascination to try and draw or paint. These three drawings I am posting are just examples. The Cedar Tree posted above, in silverpoint, was the crown of a huge old tree that had been blown down many years ago and was lying, burnished and reduced to its core, in deep marsh grasses.

Sapelo Dunes was an early morning silverpoint study of the different parts of the dunes facing the restless waves that aided the wind to shape these dunes. Holding the sand against these forces, the sea oats cling tenaciously, their roots amazingly long and lying exposed at the eroded face of the dunes.

Sapelo Dunes, silverpoint, Jeannine Cook artist

The third drawing is a graphite drawing done as the sun was setting on the wide sweep of low-tide beach, the light glinting on the marvellous ridges left in the sand by the water's motion. I was racing the light and only had a very short time before darkness fell. No time for thought, just a fascination to try and make something of nature's marvellous complexity in Low Tide Tracery.

Low Tide Tracery, graphite, Jeannine Cook artist