Lorne Coutts is a frequently quoted advocate of drawing. One of his statements that resonates the most - understandably - is: "Drawing is risk. If risk is eliminated at any stage of the act, it is no longer drawing." (Trying to find out more about Lorne Coutts leads one to mysteries - borne in 1933, he has apparently published one book, in 1995. Entitled The Naked Drawings, it is out-of-print, with "image unavailable" on almost every listing - what a surprise!

In any case, everyone who has ever launched into drawing, especially without the psychological support of an eraser, knows that the results are a gamble. Even the most skilled of draughtsmen will have a surprise sometimes, a huge success but also, potentially, a total disaster. Just as the thoughts we think and the words we utter sometimes surprise, delight or dismay us, so too the lines that we place on a drawing surface can be a high-wire affair.

Even the very first lines made on the rock faces of caves such as Lascaux, France, showed that those artists, working some 40,000 years ago, were not only daring in concept and mastery of line, but they combined these aspects with the understanding of how to use the protuberances of the rocks to add extra impact to their drawings.

Lascaux

Think of the amazing kaleidoscope of drawings, often very gestural, that show how the artist is combining eye-brain-body/hand coordination and skill to produce a series of marks on a surface. Western art is rich in such drawings, as is Eastern art. Think of Leonardo da Vinci's work in chalks, for instance, or go to the other side of the world, to Japan, for drawing with brush and ink.

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the Heads of Two Soldiers in the Battle of Anghiari (1504-05). Image courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Sekkan (active 1555-1558) Monk Riding Backward on an Ox. Hanging scroll; ink on paper Image: 13 7/8 x 16 7/8 in. The Phil Berg Collection. Image courtesy of Museum Associates/LACMA

A little earlier, about 1510-15, back in Venice, Titian's searching chalks were recording this sensuous, thoughtful Young Woman, the lines probing and balancing - a deeply intense study.

Tiziano Vecellio, called Titian (Italian, ca. 1485/90-1576). Study of a Young Woman (detail), ca. 1510. Black and white chalk on faded blue paper. 41.9 x 26.5 cm (whole drawing).

© Prints and Drawings Department, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

There were so many extraordinary master draughtsmen during that period, from the Renaissance onwards, who could create fireworks and pirouettes of drawings - Michelangelo, Raphael, the Caracci brothers, Mantegna, Dürer, Caravaggio, Rubens, Tintoretto, and many, many others. One of the 17th century giants was of course Rembrandt. Just look at Rembrandt van Rijn's quick drawing of the two adults with the serious little child, or his flying strokes as he depicted this amazing lion.

Two women teaching a child to walk, Rembrandt, 1635-37. Red chalk. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Extinct Cape Lion, Panthera leo melanochaitus, Rembrandt, 1650-52. Ink. Image courtesy of the Musee du Louvre

Jumping to the late 19th/ 20th century, the high-wire act still goes on for some artists who draw, draw and draw. Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele are two Viennese artists famed for their drawings.

Egon Schiele, Crouching Woman, 1918

Another amazing draughtswoman working in Germany about the same time was Käthe Kollwitz. Constantly risking, constantly probing, she recorded human suffering and disasters in a way that rivets and remains in one's memory long afterwards.

K. Kollwitz, Self Portrait

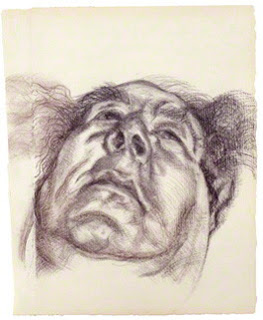

Even during the later 20th century when drawing skills were less appreciated, there were artist who persisted in working on the drawing trapezes. One of the high-flyers was Lucien Freud, who produced powerful, direct drawings, mostly of people, and sometimes his dogs.

Arnold Abraham Goodman, Baron Goodman by Lucian Freud, charcoal, 1985, 13 in. x 10 1/2 in. (330 mm x 267 mm), Given by Connectus Komonia Trust, 1986, Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

So many artists who dare to draw. They inspire the rest of us to aim for the high wires, even if the drawing only succeeds once in a while. But the more one draws, the more it becomes part of one's psyche. After all, as Keith Haring observed, "drawing is basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic."