I saw a really interesting small exhibition that came from the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut. It was at the Fundación Juan March in Palma de Mallorca and will be at the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in Cuenca from now until October 5, 2014. Josef Albers: Process and Printmaking (1916-1976) was a small exhibition, divided into three sections.

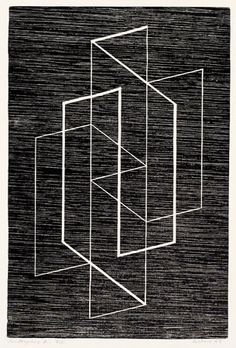

His first woodblock prints, in black and white, are a far cry from the vivid colours and abstractions of his later work in the United States.

Albers was first inspired by the coal mining landscapes of his native Northern Rhine-Westphalia region in Germany; he turned to print-making not only for its economy of production but also for the creative liberty that the medium allowed him.

He was deeply engaged, not only in the manual involvement of how art is made in the printing process, but also in the exploration of how far he could push the possibilities of the medium. Endlessly inventive and questing, he clearly kept saying to himself, “What if I did this – or that?”

Questions that every artist should be constantly asking him or herself.

One particular series was especially interesting to me, for it showed just how powerful each line can be in a drawing or print, and if one changes the emphasis of just one line, the whole composition and content of the work changes.

As Albers said, “Everything has form and every form has meaning”, and his simple series that ended as Multiplex A-D done in 1947-8, demonstrated that perfectly. Alas, his preparatory drawings which are in the exhibition don’t seem to be available on the Web. But even there, the progression of ideas and different emphasis each time on a principal line versus a secondary line underlined how Albers understood so well how art can be changed a great deal, even just by a thin or thicker line.

The preparatory drawings and studies for the Multiplex series ranged from pencil drawings on paper, then on tracing paper, sometimes using a red pencil for emphasis, sometimes a blue pencil.

Finally, having worked out the range of possibilities for that play of lines, Albers moved to studies on paper for each version of the series, then gouache over proof of a woodblock print.

Meticulous and yet questing, the preparation for such seemingly simple prints is instructive. Josef Albers had planned out exactly what he wanted to say, the emphasis each time on his view of each line’s importance. In other words, the more he prepared and thought about each work, the more pared down and powerful it became a lesson for us all!

These are the woodbock prints that are the results of the Multiplex series’ preparation.

Each line is eloquent and functions as a vital part of the composition, in a “major” or “minor key”.