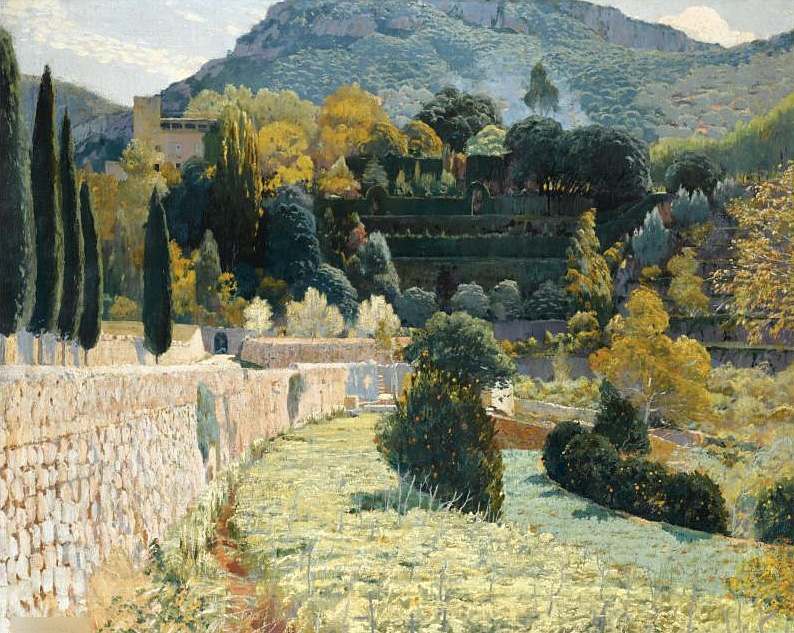

When you are surrounded by brilliant, sunlit hues and above the sky is blindingly blue, it is easy to be captivated by colour and want to translate it into your art. We all resonate to colour, and it is and always has been the dominant approach to painting. Nonetheless there are those, artists and art lovers, who also resonate to black and white and shades of monochrome in between.

I read of a perfect summation of this difference in an El Pais article about the resurrection of the Leica camera, once considered the ne plus ultra of 35 mm. cameras for most of the 20th century. Every great photographer, from Capra to Henri Cartien-Bresson used a Leica because it was quiet, highly portable and had remarkable lenses that allowed fantastic photographs to be taken. Cartier-Bresson believed too that all edits to the image should be made when the photo was being taken, not afterwards in the darkroom.

Until the digital camera came along, Leicas were much esteemed. When the then nearly bankrupt company was bought out in 2005 by Andreas Kaufmann, heir to an Austrian paper company fortune, a fascinating development occurred. Andreas Kaufmann gambled on differentiating Leicas from all other digital cameras: the M Monochrom Leica only takes black and white images. When this Leica was launched in May 2012, the model was priced at a cool 6,800 euros. It has become a runaway success in the photographic world, selling like hot cakes through Leica Boutiques around the globe.

As Andreas Kaufman was quoted as saying, “For me, colour is more emotion, while black and white represents structure.” The remark resonated with me.

True, I was brought up with a grandfather and mother both photographing in black and white in East Africa. In fact, they were so successful that they kept the farm going on photographic sales during the dreadful Great Depression years when the farm was in its infancy and barely sustained them as a family. I have always considered black and white photographs of the 1930-50 era in Europe as marvellous works of art, as well as the amazing photographs that Edward Weston and Ansel Adams took in the earlier 20th century.

I also love black and white drawings for their immediacy and unadorned truth of execution. Look at this one for direct simplicity and power of composition.

Even black and white paintings have an impact that indeed speaks of structure and logical thought.

It is as if you can get your teeth into a black and white work of art, while one in colour is a fraction fuzzy, tugging at emotion and heart strings. Portraits, landscapes, even still life or abstracts: they all evoke passion, sympathy, joy, sorrow, lyricism. Black and white images seem more cerebral, more challenging often. I find it logical that I am more and more fascinated by metalpoint drawing – it is all back to black and white.

Plus ça change, plus ça reste la même!