This is one of the most iconic parts of that vast series of paintings, when God gives Adam the gift of life.

Artists explored every way they could conceive of conveying interpretations of creation, as written in the Bible. Some of this art also spoke of joie de vivre, of sensuous love, of beauty and of life. Nature came once more into prominence, as it had been in earlier Medieval art, when depictions of flowers, birds, and landscapes had symbolised holy matters. As the 16th century moved on in Italy, for instance, more and more artists were combining the richness of the new technique of oil painting with their draughting skills. Their subjects expanded to landscapes, cityscapes, everyday scenes – art where creation could have a much wider meaning. The same movement was happening in Northern Europe.

Rembrandt, for instance, was magisterial in his ability to create art that evoked deep meaning about creation, about man's condition, and - sometimes - joie de vivre. Interestingly, as highlighted by an exhibition this year at the Louvre and at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rembrandt broke with artistic tradition by using Jewish models to depict Christ and made his Christ a living person, not an icon due great reverence. Indeed, by the 17th century, the artistic vocabulary had become much more elastic; it could allude to many more emotions that were not so dictated by religious concept.

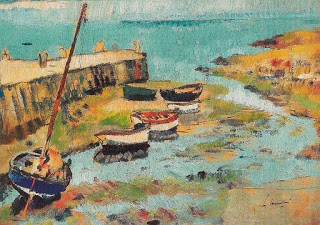

As art - and Western society - moved on through the centuries to our own, both the definitions of creation and joie de vivre have evolved hugely. Art became less and less "coded" and straightforward, so that knowledge of symbols, especially religious, became unnecessary. There can of course be many layers of meaning, but most paintings can be read to some degree, with consequent enjoyment. (Think of people's reactions to Impressionist paintings, or those of 20th century artists.) Nature has always contributed greatly to the joie de vivre of viewers, from flower paintings onwards. Now the parables of creation are more about general celebrations of life, our world in general.

Meanwhile, other civilisations' art (China, Japan, Korea, India, Islamic art, etc.) have been equally eloquent spokesmen for parables of creation - just in totally different fashion. In truth, personally, I have always found Japanese art totally intoxicating in its beauty and thus,joie de vivre.