I was preparing an artist's statement for a submission for my art to be considered today, and found myself - again! - referring to the concept of nature's beauty being an inspiration and an aid to people finding serenity. I find it endlessly interesting to see how and why people talk of beauty, in any form.

Roger Scruton, in his 2009 book, "Beauty", writes: "The judgement of beauty is not merely a statement of preference. It demands an act of attention. Less important than the final verdict is the attempt to show what is right, fitting, worthwhile, attractive or expressive in the object; in other words, to identify the aspect of the thing that claims our attention." He inveighs against kitsch and the seemingly prevailing ethos that allows us often to live in denial of any sacrifices, any effort to cater to our higher nature, an attempt "to affirm that other kingdom in which moral and spiritual order prevails."

Sir Roger Scruton

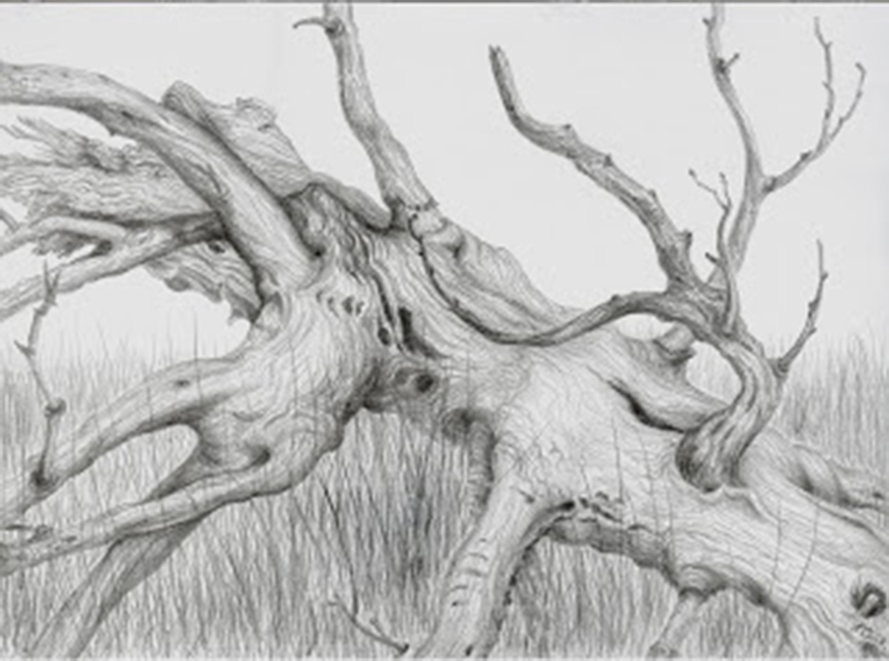

I think that most of the artists I personally know are indeed seeking, consciously or not, to show what is "right, fitting, worthwhile, attractive or expressive" in the subject matter they are depicting. The way they depict the material is almost secondary. Certainly I find myself captured by the beauty of nature as I experience it here in coastal Georgia or in parts of Europe that I know. Working plein air, I find that I round a corner and see something that stops me in my tracks, saying insistently, "Pay attention to me, I am important". Often, later, I realise I was drawn by a form of beauty, some elegant shape or intricacy, or an example of something noteworthy, such as the endurance of a tree against all odds. That subtle dialogue is unfathomable to me, but it surely exists. One knows instinctively that the beauty one is seeing is of value for its own sake, taking one into a realm that is almost deliciously childlike, where imagination and serendipity can reign. Once the technical considerations of how to tackle the painting or drawing are finished, I find I can stop thinking consciously and just do.

The other mysterious aspect of this dialogue is that later, other people frequently respond to the image I created. Somehow, if one is fortunate, one has tapped into something greater than oneself, into the realm of the beautiful, the worthwhile.