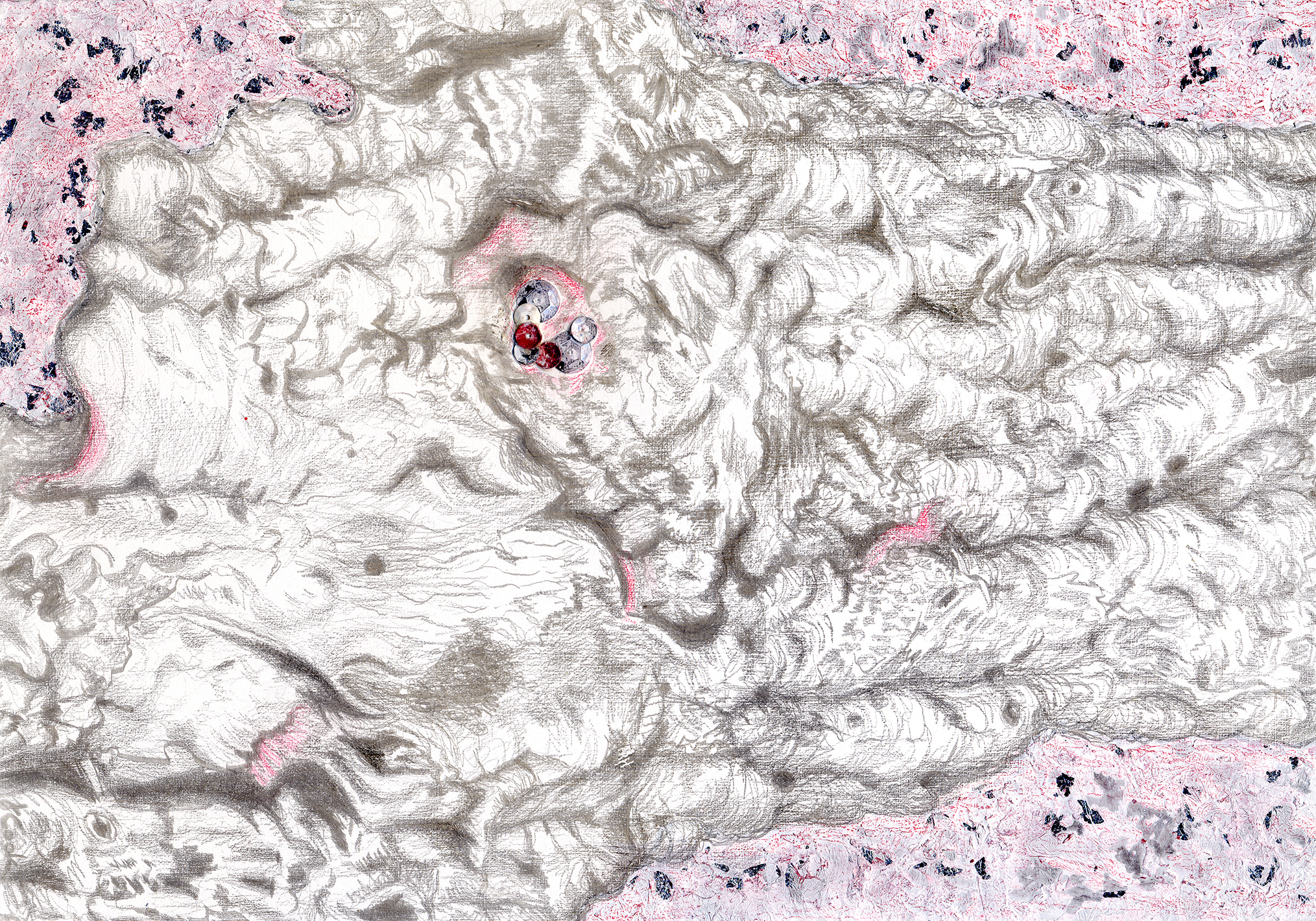

Recently, a dear friend and truly wonderful artist, Susan Schwalb, galvanised me into doing something that I had been thinking about since my mother's death: drawing in silver on a black background, versus a white ground.

I had been feeling that perhaps a series of drawings in black might help deal with my mother's absence. So when I was in Spain, I prepared some small pieces of paper and launched myself into a new version of silverpoint. It soon became a fascinating exercise, for in essence, you suddenly change your visual thinking and vocabularly completely. You need not only to reverse everything, but detail of course disappears on the black ground unless you are very careful. So you need to select subject matter very carefully. I am still very much feeling my way, but it is a reinvigorating challenge!

I decided to do a series entitled Apoyos which is "supports" in Spanish. My mother loved trees; they were her literal and metaphorical supports on many occasions.

Apoyos I - coffee tree bark - silverpoint, Jeanine Cook artist

Apoyos II - Eucalyptus tree bark - silverpoint, Jeannine Cook artist

So I drew the bark of different trees she cherished, from a wild coffee tree grown from a seed from our farm in Africa , to a graceful elm, to a Mediterranean pine she loved and laughed about. I had transplanted it as a seedling, in preparation for a bonsai pine. It is now nearly forty foot high!

Apoyos IV - Pine tree bark - silverpoint. Jeannine Cook artist

Each of these drawings is tiny, only 5 x 3.5 inches, but they helped me center myself and remind myself that there are so many different ways to express oneself in art.