Joan Miró

The Fundacion Pilar I Joan Miró a Mallorca is a wonderful place in which to spend a hot summer morning. From the sunswept terraces that overlook the brilliance of the Mediterranean to the cool, diffuse light of alabaster screens in the exhibition spaces, all the senses are awakened by unexpected juxtapositions of interest and beauty. Rafael Moneo designed the exhibition spaces as a complement to Miró’s studio and Pilar and Joan Miró’s home. Gardens and reflecting pools are glimpsed from the building through often low windows, enhancing the building’s spaciousness and its spare simplicity.

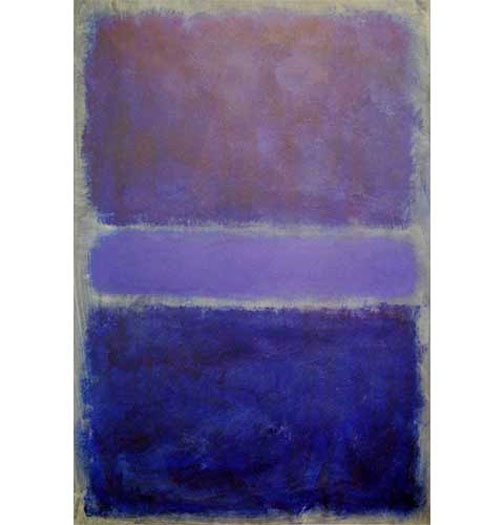

In a way, the buildings follow a concept that Miró enunciated about his paintings in black and white. Writing in 1959, Miró said, “My wish is to achieve maximum intensity with minimum means”. Many of his paintings verge on the oriental in many ways during this period.

His desire to use an intense but spare vocabulary in monochromatic work resonated with me, for increasingly, that is what interests me in my metalpoint drawings. How to say a lot in a condensed or powerful fashion, using the minimum of means. In truth,metalpoint is such a simple, humble drawing medium: just a piece of metal, making marks on a smooth surface prepared with a ground. Its range of tones is limited, its scale often limited because of the slowness of execution, its discipline of technique demanding. Yet despite all that, like Miró’s black and white paintings, metalpoint at its best is quietly powerful. Its lustre is alluring and unusual, its economy of form arresting.

One of the masters of silverpoint/metalpoint was of course Leonardo da Vinci. He led the way in the maximum impact-minimum means league.

Another silverpoint artist working today with a very different approach is Roy Eastland, a British artist. Nonetheless, to my eye, he is highly successful in the impact he achieves with the humble medium of silverpoint.

One of my minimalist recent metalpoint drawings owes its origins to the patterns I saw recently on a huge plane tree one hot July day in France.