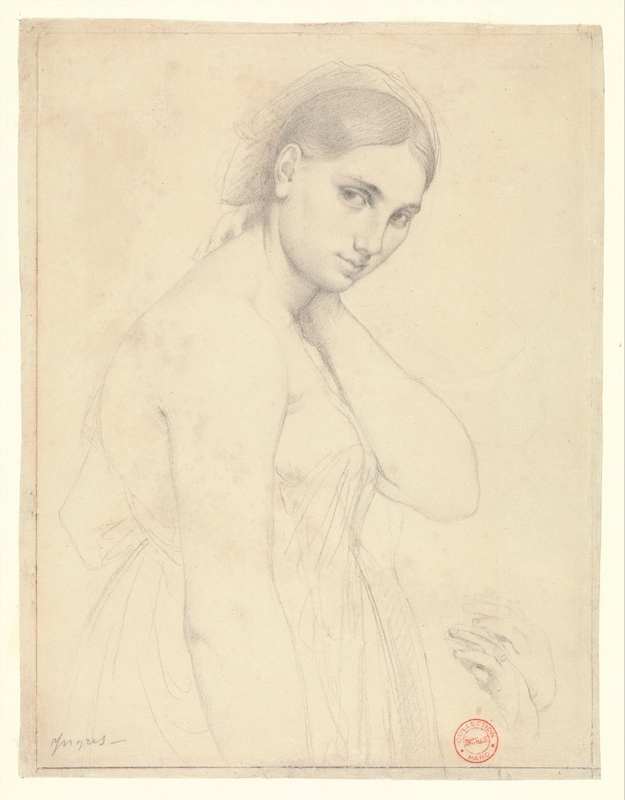

Thanks - once again! - to ArtDaily.org's listings, I happened on an up-coming Sotheby's sale of old Master Drawings from a private collection. I spent a fascinated hour on their site, going through the E-Catalogue of the drawings, some eighty of them, the ideal occupation for a dark, rainy day.

It is always extremely interesting to view a collection of art formed by one person, particularly a person who has a trained eye and knowledge of the media involved. I quote from the news release about this collector (who apparently spent about 25 years assembling this collection). "In his very personal forward to the sale catalogue, the collector who assembled this remarkable group of drawings wrote that he embarked on collecting “with the bold aim of looking over the artist’s shoulder”. There can be no question that he succeeded in this aim. The light that these extremely varied studies shed on the artistic creative process is both intense and wide ranging: we see every moment in the artist’s thought process revealed and illuminated."

There is a remarkable energy and life evident in the drawings this collector assembled. The artists are clearly in the throes of excitement and creativity. Famous names or not, it does not matter. The hallmarks of these drawings are immediacy, directness, sureness of touch and stroke. The collector does indeed describe well what he sought - and found - when he selected these works. Different media, different subject matter, some clearly well thought-out and planned, others on the spur of the moment, catching images almost on the fly... Some as aide-mémoires, others as exploration. In short, the collection came across to me as a most interesting selection of artists' emotions, desires, endeavours, aims... running a gamut of approaches and techniques. Little interesting items too, such as remarks about an exquisite study of a seated woman by Jean-Antoine Watteau. "It was executed in a combination of media that Watteau used only occasionally, but to striking effect: the majority of the figure is built up with a network of silvery strokes of graphite (a very rare medium in Old Master Drawings), (my emphasis) while the accents in the face and hands are in a more typical red chalk, an extremely effective juxtaposition that creates a lively yet utterly elegant figure."

When you go back and try to find out about the use of graphite before the early 18th century, it is indeed hard, as a neophyte, to find allusions to many graphite drawings. Pure graphite, first mined in Borrowdale, England, in the 1500s, seems initially to have been used for under drawing in the 16th century. It was more forgiving than metalpoint, especially silverpoint, the draughtsman's favoured medium during Renaissance times in spite of silverpoint's linear qualities and permanence of mark. Graphite does not seem to have been used much for drawing until well into the 17th century. Artists tended to favour chalks, red and black, as well as charcoal for studies and finished drawings alike. (Interestingly, the Venetian artists continued to favour black chalk, whilst the perhaps more flamboyant Florentine and Roman artists preferred the harder red chalk with which they could show off their skills!) Graphite became widespread only in the 18th century, with the increasing difficulty of obtaining good-quality natural chalks and the simultaneous production of a fine range of graphite pencils after the invention of a graphite pencil in Nuremberg in 1662.

Graphite drawings then become far more widespread: John Constable, Jongkind and later John Singer Sargent, for example, all used graphite in their work, particularly when working plein air.