It is thought-provoking for every artist to see Albrecht Dürer's statement that "Simplicity is the greatest adornment of art". In some ways, it is a bit ironic for Dürer was perfectly capable of making complex, crowded works of art, especially his woodcuts.

Hands of an Apostle, Albrecht Dürer, (image courtesy of GraphischeSammlung Albertina).

Nonetheless, the image that of course comes first to mind when I read his remark is his super-famous Hands of an Apostle, a grey and white drawing on his favourite blue paper. This drawing was done in preparation for the Frankfurt church altarpiece that Jakob Heller commissioned him to paint in 1508. This is indeed a devastatingly simple drawing in one sense, but look at the rendering of the skin texture, the way Dürer conveys the gentle meeting and touching of the finger tips, as well as the effort of keeping the hands together, despite their weight. The blue paper used, "cartaazzurra", was a new enthusiasm for Dürer; he learned about it when he went in 1507-08 to Venice. Artists in Northern Italy had been using it since 1389, and Venetian artists favoured it because it allowed them to use wonderful chiaroscuro effects.

Twelve-year Old Christ, drawing, Albrecht Dürer (image at right courtesy of the GraphischeSammlung Albertina).

He was using this paper again for this study of the Twelve-year Old Christ, an extraordinary, sensitive and yet very straightforward drawing.

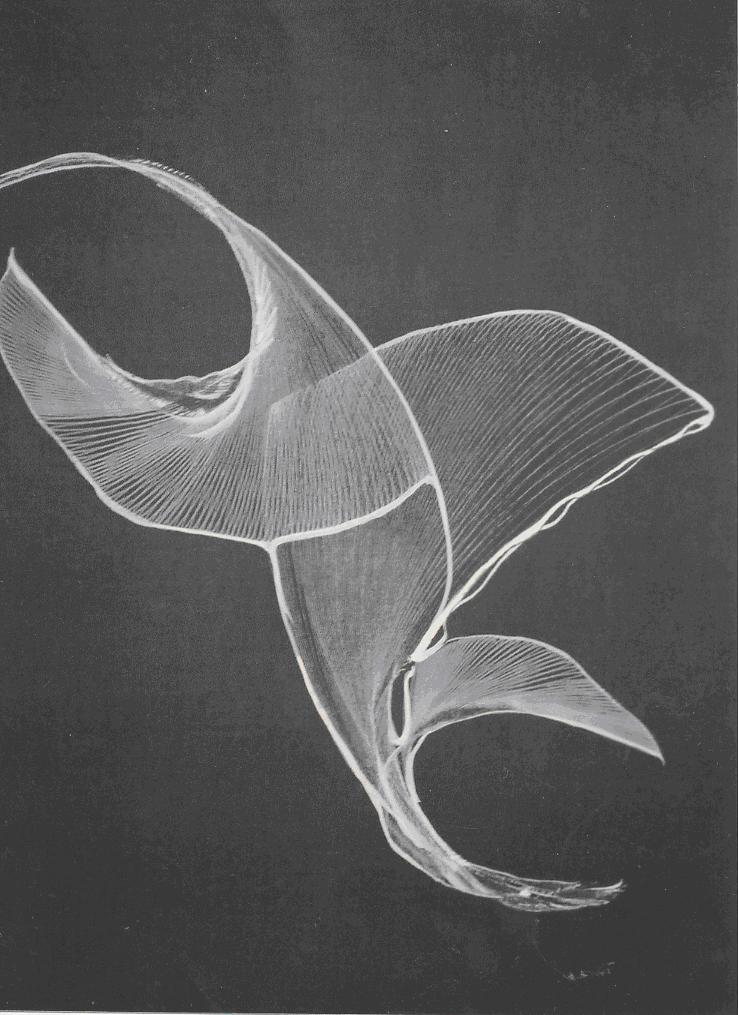

Dürer continued to use this paper and took a goodly supply of it back home to Northern Europe. I remember reading somewhere that when he ran out of it, he went to great lengths to find alternative blue papers. This drawing of the Arm of Eve was again, a very simple, powerful drawing Dürer did on blue paper in 1507.

Arm of Eve, drawing on blue paper, 1507l Albrecht Dürer (image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art)

I think that it is a real discipline for each of us, as an artist, to try to simplify our work, to distil it to its essence, not to dilute and maybe obscure the message. There is always the temptation to add in more detail, more complexity. When you think of it, however, that a simple study, drawn 503 years ago on a small piece of blue paper, can remain so memorable, so vivid, so powerful is a total confirmation of Dürer's statement about simplicity being the greatest "adornment of art".