One of the delights of travelling is being surprised by new discoveries. A visit to Boston’’s museums was full of such rewards but one especially so. In the Museum of Fine Arts, there is a current exhibition entitled “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death”. After going through the several rooms displaying his art, I was both fascinated and hugely impressed. At the same time, I felt yet again ignorant for Bloom was clearly a marvellous, versatile artist and draughtsman who achieved success in the United States, especially in the 1940s and 1950s. Granted, he has apparently since been “overlooked” as the text tactfully said, but there is now this big exhibition of his paintings and drawings for new generations to learn about his work.

Bloom was born in Latvia in 1913, but by 1920, his orthodox Jewish family of leather workers decided to emigrate to the United States to escape the persecution of Jews in their impoverished area. Two sons went first and then the rest of the family joined them in Boston to continue in the leather business. Hyman first wanted to train as a rabbi but since there was no one to train him, fate intervened; his artistic gifts were recognised and he ended up in a programme for high school students at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. His later training was rigorous and classical; he learned both to draw superlatively and to handle paint in the same manner as earlier master artists. How more luscious a paint-handling can one get than in this still life?

Turban Squash, 1959, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

What initially drew me to his work was his interest in portraying things realistically but close up and in such a way that they appear abstract. In fact, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning considered Bloom to be America’s first abstract expressionist. He sought to get beneath the surface of things, interested in inner truths and the cyclical nature of life and death. Using a flattened perspective, overall composition and gestural brushstrokes in a wonderful spectrum of colours, Bloom sought the inner meaning of things, the unseen.

Rocks and Autumn Leaves, 1949-51, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

The Stone, 1947, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Archaeological Treasure, 1945, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Be it shards and amphorae in “Archaeological Treasures” above, or another form of very still life in which Bloom got fascinated, he was constantly searching for more than what initially meets the eye. One of his quests, from 1943 onwards as a result of an initial chance visit with a fellow artist to a morgue, was to explore the innate beauty and meanings of cadavers, human or animal, and how they look when they are dissected. I found it somewhat unnerving at first glance to see some of the canvases and drawings in this section, but then, remembering back to the rather low-key and bloodless paintings Chaim Soutine did of slaughtered animals, the impact of Bloom’s work compels a serious study. Clearly Bloom saw great fascination in these bodies: in fact, he is quoted as saying, “The body is very beautiful and its insides are just as beautiful as its outsides.” He apparently studied medical textbooks and attended autopsies and dissections, making careful drawings, and then composed his powerful explorations of flesh and bones. Despite a heritage of human dissection being portrayed by such artists as Leonardo da Vinci or Rembrandt, the 1940-50s public viewing such paintings by Bloom were shocked and unnerved by his powerful renderings of cadavers.

Slaughtered Animal, 1953, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

As a draughtswoman, the other section of the Bloom exhibition that I found so wonderful was his drawings. Apparently Bloom had always drawn well and then was superbly trained, both from real life and also using his imagination to produce drawings, in various media. Everything was grist for his mill: he drew from nature - trees and landscape, he did a long series of old women, poignant and unsparing. He echoed classical artists in his studies of wrestling figures. All were assured and accomplished, with an attention to detail and innate sense of powerful composition that were wonderful.

Wrestlers, graphite and black chalk, 1930, Hyman Bloom (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago)

Old Woman Climbing, undated, conte crayon on paper, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Trees (Dark against Light), 1962, charcoal on paper, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Tree (Light against Dark), 1962, charcoal on paper, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook),

Bloom clearly had infinite patience for these drawings of bare trees are very large and their complexity impresses. Again, I got the impression of deep meditation about cycles of life as he created such drawings. In the same way, his sensitivity about ageing, life and death, the hidden marvels beneath each surface spoke of great thought and compassion, and a reverence for all aspects of nature. No wonder he wanted to be a rabbi. In fact, he also painted portraits of rabbis and even the marvellous chandeliers in Boston’s many synagogues; two canvases on exhibit date from 1945, when Bloom must have been thinking deeply about the fate of Jewish people in a Europe shattered by World War II.

Older Jew with Torah, 1945, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Chandelier No 2, 1945t, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

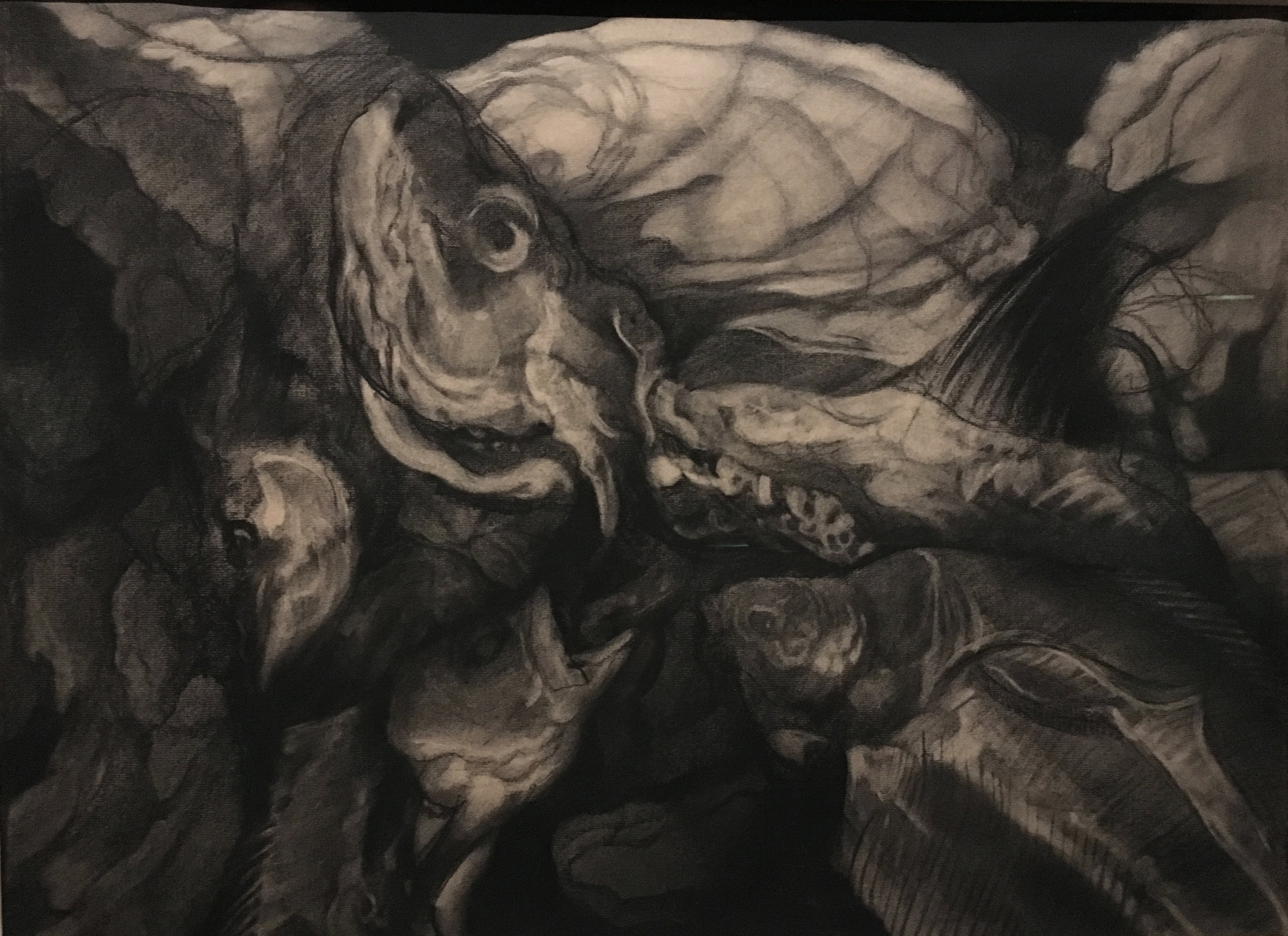

No subject was lacking in interest. His studies of fishes, and resultant paintings are as contemporary as any today.

Fish, Still Life, 1953, charcoal on paper, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Seascape II, 1974, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

Bloom began painting seascapes in the 1970s, mixing living fish in with their skeletons, a metaphor for the treachery of the sea and beyond. In fact, he explained, “Eating, pursuit and dying: it’s a euphemism for free enterprise, a predatory competition. Life is a contest.”

The Museum of Fine Art’s exhibition on Hyman Bloom was large and many-faceted. The overall impression I gained was of a superbly gifted artist whose questing spirit and deep interest in all aspects of life and death, and the innate beauty one can find at every stage throughout life, pushed him ever onwards to explore and celebrate. He lived until 2009, but I suspect that this exhibition will garner new appreciative publics.

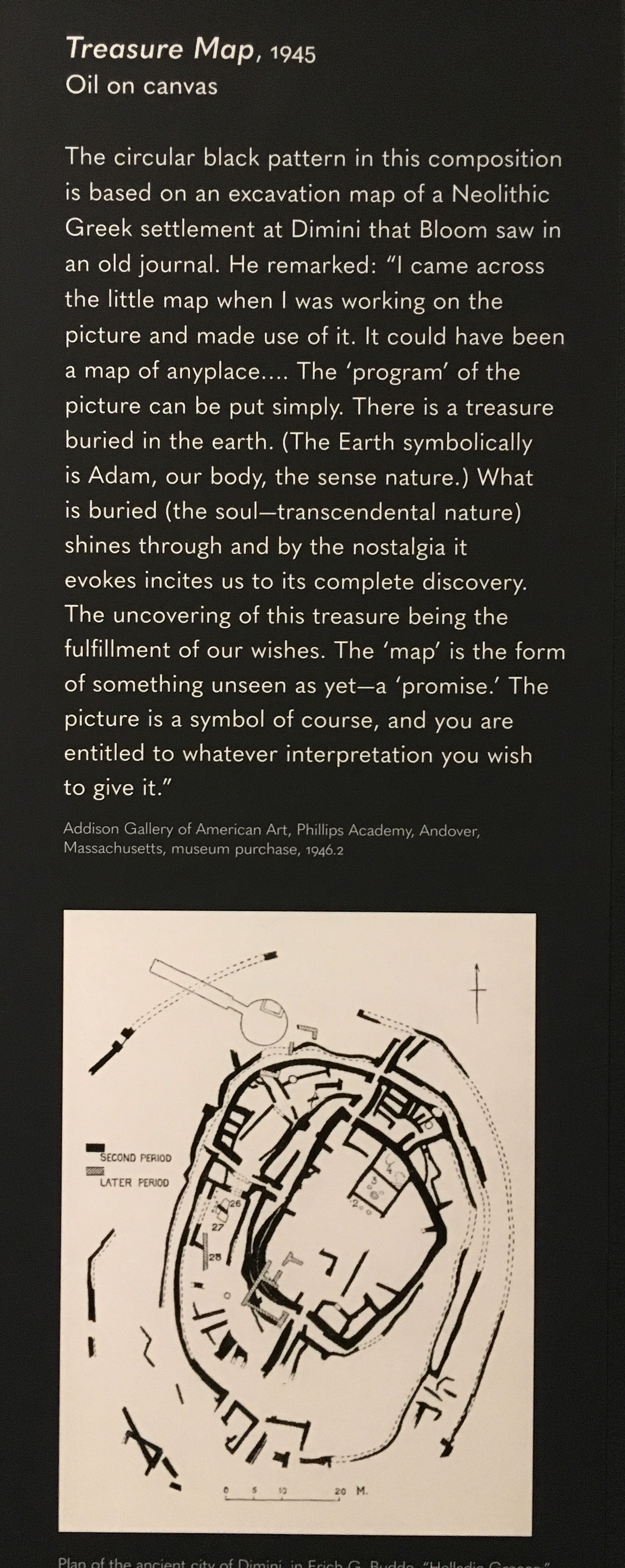

Perhaps a wonderful paintings done in 1945 became for me a metaphor for Bloom’s life of creating deeply thoughtful, stirring and beautiful art. Treasure Map, with its museum label and explanatory drawing, says it all.

Treasure Map, 1945, oil on canvas, Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)

MFA label accompanying Treasure Map painting by Hyman Bloom (Photograph J.Cook)