Leonardo da Vinci, that omniscient artist, once remarked, “I have seen shapes in clouds and on patchy walls which have given rise to beautiful inventions.”

We have all seen wonderful shapes in clouds as they sailed above our heads – that is a gift that one should never lose.

Patchy walls – that is another affair in today’s world.

Most cities are now more characterized by glass and steel and other slick-surfaced materials that don’t often inspire the imagination in the way that Leonardo meant. Yet, when we visit the older towns and villages of the world, particularly in areas where stone and wood have been the predominant building materials down the ages, the imagination can again take flight.

In Caylus, France, the walls of the medieval houses are a history of generations of people building, adapting and shaping the stones and bricks of their abodes. The abstract patterns and wonderful shapes delight and interest.

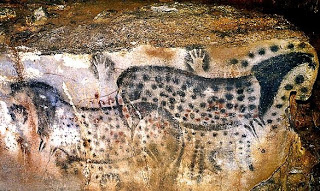

In fact, the whole region rewards the imaginative eye. See what you think.

Oak beam end (artist's photograph)

Caylus (artist's photograph)

Caylus (artist's photograph)

Caylus (artist's photograph)

Caylus' history in the walls (artist's photograph)

Another version of a patchy wall (artist's photograph)

Leonardo da Vinci would have been delighted in southern France. The walls lend themselves to all sorts of flights of fancy. Just what an artist needs and wants!