January and February in Mallorca, Spain, are months of delight for those of us who love almond blossom. The island is transformed into fairyland, with row upon row of pink and white blossom undulating through the valleys and over the plains, always with the backdrop of dramatic blue-green mountains and azure winter skies. Beneath the trees lie carpets of emerald winter wheat sprouting or grazing land that is dotted with huge herds of shaggy sheep, often with early fragile lambs. The incredible winter light playing over the blossom is crystalline and renders every detail vivid and gem like.

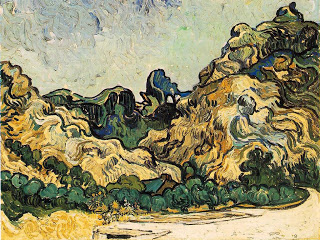

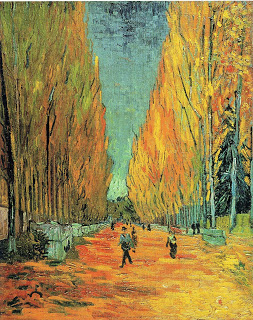

Almond blossom not only plays an important role in ensuring the production of almonds, always an important crop, and a major tourist attraction in Mallorca; it has also inspired many artists. Perhaps the most famous among these artists were those of the 19th and early 20th century, many of them from Catalonia, who visited the island and were captivated by the island landscapes and. above all, the light here. Even Joaquin Sorolla exclaimed, "This light, this light, it is impossible to capture it!" ("Esa luz, esa luz, es impossible capturarla!").

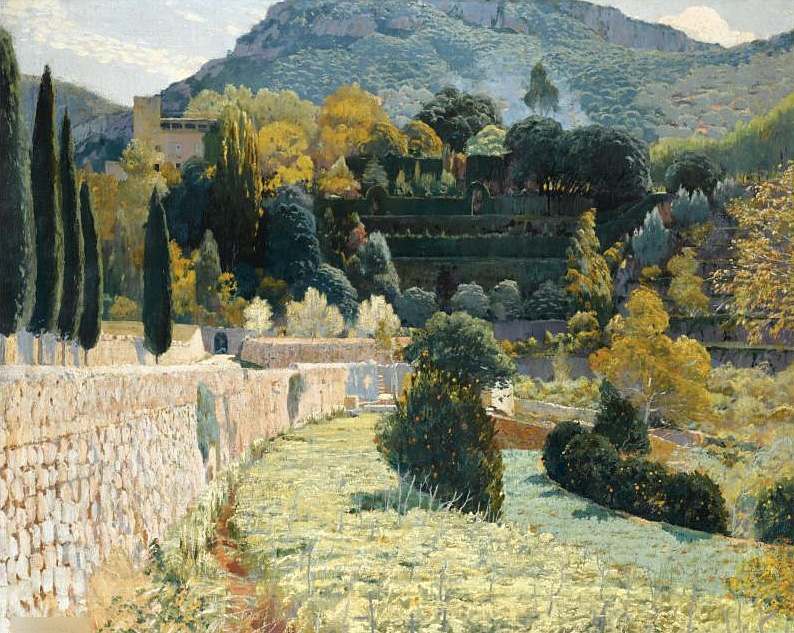

One of the most famous of the Catalan painters who became one of Mallorca's leading landscape painters was Santiago Rusiñol i Prat. He was also a noted writer, poet and playwright. Born in 1861, he came first to Palma in 1893. After spending time in Paris, he returned to Mallorca in 1901, partly to get over a drug addiction. From then on, he spent a great deal of time on the island, celebrating its scenery, gardens and flowers. In 1912, he also published La Isla de la Calma, a paen to the Island of Calm, Mallorca, that he believed was a bulwark against the increasingly frenetic industrial and materialistic world elsewhere.

Terraced Garden in Mallorca, Santiago Rusiñol, 1904

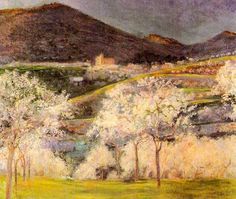

Santiago Rusiñol was often accompanied by artist friends during his stays in Mallorca. Joaquin Mir (1873-1940) was one of his companions, and lived for four years in Mallorca from 1901 onwards, often in the north of the island around Pollensa.. He became known as the father of Mallorcan impressionism, having evolved from an early much more personal approach to painting, when he merged form and colour. Mir too fell under the spell of the springtime almond blossom around the island.

His early paintings of spring differ greatly from his later work, but all sing of Mallorca's light and extraordinary beauty that comes in January and February.

Another of Santiago Rusiñol's friends in Paris and Barcelona was Eliseu Meifrèn i Roig, (1857-1940), a Catalan who travelled widely and was highly respected for his plein air approach to landscapes. He too came to Mallorca as the new century dawned; ultimately he became director of the Art School in Palma in 1910. His paintings of almond blossom are lyrical.

Eliseo Meifrén taught another Palma-born artist who became very well known for his paintings of Mallorca, Joan Fuster Bonnin (1870-1943). Talented and prolific, he was friendly with Santiago Rusiñol and Mir, and later, with another very successful artist in Mallorca, Anglada Camarasa.

How many paintings can one appreciate of almond blossom? I don't know, but I do know that the late 19th and early 20th century saw an amazing number of artists tackling paintings of these almond trees in flower. Incidentally, these blossoms are rather short-lived, for winter winds and rain play havoc with them, and within the space of a week, the tender brilliantly green pointed little leaves begin to replace the pink or white blooms.

Another four examples of artists who loved Mallorca in January and February. Take your pick!

Perhaps the suitable footnote to all the artists' paintings of Mallorca's almonds and the light in which they sparkle is to add the fact that almonds are the earliest domesticated tree nuts, originating in the Levant and spreading through the Mediterranean basin. It is thought that almond trees were first introduced to Mallorca during the Roman times, after Quinto Cecilio Metelo conquered the Balearic Islands in 123 BC. When grapes were so badly affected by phylloxera towards the end of the 19th century, the Mallorcans planted almonds as a replacement crop. Thus the Catalan and Mallorcan artists had such wonderful panoramas of almond trees in flowers to delight and inspire them.