For a long time, I have found that in many instances, what I draw is seemingly dictated to me by happenstance. So when I read a quote from Maggie Hambling, one of Britain's leading figurative artists, about subjects choosing her, it resonated! She said, "I believe the subject chooses the artist, not vice versa, and that subject must then be in charge during the act of drawing in order for the truth to be found. Eye and hand attempt to discover and produce those precise marks which will recreate what the heart feels. The challenge is to touch the subject, with all the desire of a lover."

Read MoreDrawing

The Power of Line /

Ever since I started looking closely at drawings deemed “master drawings” in the first drawings exhibition held at the Louvre in 1962, I have been fascinated by the implications of the power of a line. No matter what period, Renaissance, Baroque, 17th or 19th century, the artist can say volumes merely by a line in a drawing. It does not even need to be a line that is perfect. Frequently lines that are re-drawn, adjusted and reinforced are extremely powerful and eloquent. The line can whisper and hint, it can assert, it can describe, it can evoke or imply. A line, in essence, can take on a life of its own, transmit it to the viewer and empower a dialogue between image drawn and the viewer that can be subtle and long-lasting.

Read MoreHokusai's Example /

When I was looking a the lovely collection of Hokusai's small and intense drawings in the Museum at Noyers sur Serein, I kept thinking about his enthusiastic approach to drawing. A brief quote of his about drawing, "Je tracerai une ligne et ce sera la vie", seems such a lofty goal to which to aspire as a draughtsman or woman. It stopped me in my tracks, because it implies such a deep, wide approach to making marks and creating a drawing. The quote in fact is part of a much larger and famous statement Hokusai made about drawing. Hokusai Katsushika, the long-lived and richly productive Japanese artist whose most famous series of woodcuts is probably the Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji, lived many iterations of an artist's life from his birth about 1760 to 1849. He drew obsessively.

Read MoreBurgundy Drawings /

Ammonites de Bourgogne, silverpoint, watercolour, Jeannine Cook

It is done – I have managed to produce 15 drawings for the exhibition at the Musée de Noyers! What a relief! I deliver them next Monday and the exhibition will run concurrently with the show I have hanging at the gallery at La Porte Peinte.

Preparing for an exhibition under deadlines is never a favourite occupation for any artist. However, some people do work best like that. I am not sure that I do – the results of the effort will be for others to judge!

What has been both interesting but also more complex has been the need to weave together a body of work that pertains to the ideas I put forward originally, namely the birth of metalpoint drawing in the scriptora of monasteries, where monks used lead to delineate the illuminations and trace lines for the script of their illuminated manuscripts. Combined with that history, I wanted to celebrate the tiny fossilized oyster shells found in the Kimmelridgian layers of soil found especially in the Chablis area and which contribute to the special terroir of those wines. I had picked up samples of these heavy stones when I first arrived in Burgundy last year, and they have led me on a fascinating odyssey.

Tying the metalpoint’s history together with the fossil-laden stones was thanks to those industrious monks who in medieval times also helped to spread the cultivation of wine, as they founded the great monasteries in Burgundy. Vezelay, Fontenay, Pontigny: they are all centers of such a rich heritage.

Even the wonderful and mighty plane trees, such as one sees at Fontenay that was planted in 1780 by the Cistercian monks, ten years before they had to leave their monastery, was part of that long-standing monastic heritage that enriches us all.

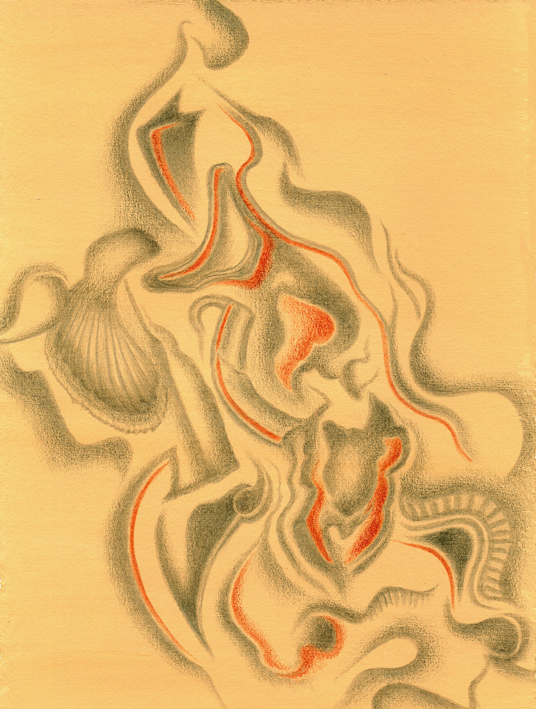

The other aspect that I tried to incorporate into these drawings is the close links between Burgundy and ocre, one of the key pigments in man’s artistic endeavours since the earliest marks man-made on cave walls from Australia to Africa to Europe. Burgundy was famous for its yellow ocre deposits and only ceased to produce ocre pigments in the 20th century. By heating yellow ocre, red ocre is produced; the two pigments find their way into every drawing and painting imaginable down the ages. I used the two colours as tinted grounds for some of the drawings I did for this project. Since early times, some artists used tinted grounds for their metalpoint drawings, so again, I was following a long-standing tradition.

I loved finding out all sorts of things about history and aspects of beautiful Burgundy for this project. It has been such fun - the drawings have been the perfect vehicle and excuse for all sorts of new insights and investigations. It is marvellous when art and fresh knowledge can go hand in hand.

Forms of Still Life /

Inching my way back from the roles of hospital companion and guardian to my husband as he recovered from an emergency operation, I finally felt I could slip back into my artist world a little. It was a welcome move as there is nothing more debilitating, for patient and family, than sojourns in a hospital. My first treat to myself was to see a recently opened small exhibition at the Museu Fundacion Juan March in Palma de Mallorca. Entitled "Things: The Idea of Still life in Photography and Painting", it straddled 17th century Dutch still life paintings and late nineteenth-early twentieth century photographs.

It was a really interesting premise, examining the forms of still life and even the cultural differences in the use of the word, "still life". The German and English versions of the words echo the original Dutch/Flemish concept of examples of things that are faithfully recorded in a carefully organised composition. But the Spanish "naturaleza muerta" or 'bodegon" stray far from the original premise. Most of the work presented represented northern artists, thus closer to the true sense of still life.

The Dutch paintings were lovely small ones, where the artists had delighted in the play of light on a glass goblet or a small ceramic dish, spoon or the crisp glint of a peeled lemon.

The leap to the early medium of photograph to record still life that, mostly, was pre-composed, was interesting. Sometimes, the photographs seemed airless, compared to the paintings, still a characteristic of many photographs today when compared to paintings. Yet there was an elegance and refinement in the photographs that were distinctive. As always, I seem to prefer the very simple compositions - such as one by Baron Adolphe de Meyer taken in 1908 of two hydrangea flowers in a glass of water, the reflections of the glass playing out on the wide expanse of the surface in the lower third of the photogravure.

The selection of photographic still life works was wide-ranging - from daguerreotypes to a coloured autochrome coloured back-lit plate of flowers by the Lumiere Brothers done in 1908, a circa 1895 trichromatic print of flowers (so much for all our modern "inventions" of technicolour) and then into the more modernist 1920-60 black and white work by Man Ray, Walker Evans, and many other European photographers.

Every interpretation of still life was there one could imagine - from carefully set up compositions, to views of life made still in abattoirs or after a volcanic eruption to Walker Evans spotting a natural still life scene on a back porch of a (sharecropper?) weather-beaten clapboard house.

As I looked at the different compositions and the elements that made up those compositions, mainly derived from nature, I could not help realising that most of my current artwork is, de facto, still life. I am using elements of nature in compositions that record stones, bark, flowers --stilled by being placed in a setting other than their original one. I have only strayed a little, like many other artists, from the path of still life "inventor" artists of the seventeenth century by cropping, zooming in on some elements and eliminating others, framing and thus altering the original concept and layout of the still life set up.

I love feeling this sense of kinship and heritage that comes when you look at artwork from previous times and understand how and why you do things the way you do, thanks to those earlier artists.

Video on Metalpoint and its Ins and Outs /

I have just received this video that video-maker Derek Gauvain made for me to celebrate metalpoint drawing. Check it out:

Wisdom from Dame Barbara Hepworth /

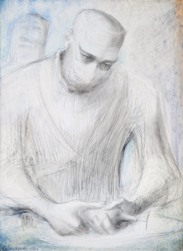

When I re-read a lecture that British sculptor, Dame Barbara Hepworth gave about 1953 to a group of surgeons, it seemed well worth repeating (courtesy of the Bowness, Hepworth Estate). Barbara Hepworth was a very good draughtswoman, and as a result of her daughter, Sarah, spending time in hospital in 1944, she became close friends with Norman Capener, a surgeon who treated Sarah at the Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital in Exeter. He invited her to be present in operating theatres in Exeter and at the London Clinic, during surgical procedures, so that she could draw different scenes of the operations. As a result, she produced, between 1947-49, nearly 80 drawings of operating rooms in pencil, chalk, ink and oil paint on board. She became fascinated by the similarities between surgeons and artists, particularly with the rhythmic motions of hands.

She wrote, after being in the operating theatre in Exeter, "I expected that I should dislike it; but from the moment when I entered the operating theatre I became completely absorbed by two things: first, the co-ordination between human beings all dedicated to the saving of a life, and the way that unity of idea and purpose dictated a perfection of concentration, movement, and gesture, and secondly by the way this special grace (grace of mind and body), induces a spontaneous space composition, an articulated and animated kind of abstract sculpture very close to what I had been seeking in my own work."

In her c. 1953 lecture, she reiterated this unity of idea and purpose.

"There is, it seems to me, a very close affinity between the work and approach both of physicians and surgeons, and painters and sculptors. In both professions, we have a vocation and we cannot escape the consequences of it.

The medical profession, as a whole, seeks to restore and to maintain the beauty and grace of the human mind and body; and, it seems to me, whatever illness a doctor sees before him, he never loses sight of the ideal, or state of perfection, of the human mind and body and spirit towards which he is working."

"The artist, in his sphere, seeks to make concrete ideas of beauty which are spiritually affirmative, and which, if he succeeds, become a link in the long chain of human endeavor which enriches man's vitality and understanding, helping him to surmount his difficulties and gain a deeper respect for life."

"The abstract artist is one who is predominantly interested in the basic principles and unifying structures of things, rather than in the particular scene or figure before him."

Une Prière à Rembrandt /

J'adore lire des remarques faites à propos de l'art de dessiner. Je suppose que ma prédilection personnelle du dessin y joue une partie. N'empêche, j'ai beaucoup aimé cette prière à Rembrandt, que j'ai trouvée dans le livre de Yankel, Pis que Peindre, publié chez Chimère en 1991. La prière: “Le régal des dessins est d’une autre nature: c’est l’émotion sur le vif, au bout des doigts. La main est là, on la devine derrière le moindre trait évanescent ou asséné. Il y a un miracle de la ligne chez Rembrandt : qu’il soit rageur, incisif, écrasé ou, au contraire, fugace, fulmineux arachnéen ; son parcours est si vrai, si juste, qu’on reste éberlue, ravi, consterné. Qu’il s’arrête pile à un millième de millimètre ou qu’il dépasse l’objectif, c’est juste comme ça que cela devait être. Instinctivement, sa ligne a trouvé ce qu’il faliait d’intensité pour réinventer une vie nouvelle sur une simple feuille légèrement teintée. Le côté fragile, dérisoire, du support, ajoute encore à l’approche extasiée que j’ai de cette rencontre avec le génie. »

Regardez les dessins qu'a fait Rembrandt de sa femme, Saskia van Uylenburch, du moment qu'ils se sont mariés le 6 juin 1633. Le premier, fait en pointe de metal, (qui ne s'efface point), est de ce même jour. Ensuite, ses études de 1636 d'une Saskia endormie ou avec des enfants, parmi d'autres, sont, pour moi, des examples de la ligne de Rembrandt au plus tendre, plus juste, plus merveilleuse.

Je crois que c’est la justesse de la ligne chez Rembrandt qui le rend si extraordinaire aux yeux de ses admirateurs, génération après génération. Chaque fois que l’on se retrouve à une exposition de ses dessins, dans une lumière tamisée, le silence et l’attention intense règnent dans les salles. Tout le monde scrute les petits dessins dont les lignes semblent faites avec désinvolture, mais avec quelle émotion, quelle vérité. Que ce soit un dessin à l’encre ou, rarement, au stylet d’argent, la ligne reste, en effet, miraculeuse.

Tout artiste admire, aspire à en faire pareil, mais – combien de fois dans la vie ? Rembrandt est unique. Tout artiste reconnait ce génie comme un cadeau aux générations suivantes. La prière de Yankel se comprend !

Artists' Philosophies /

It is always fascinating to read what other artists have thought about the state and office of being an artist. Many times, I find myself reading something an artist has written and I think, oh yes, exactly, that is what I think or feel. It is nice that there is often a community of thought between artists, even separated by many generations. I suppose it is really because the demands of art creation remain essentially those of finding a means to express thoughts, passions, emotions that can be communicated to others, visually, audibly, in tactile fashion. In a way, an artist is, willy nilly, a conduit for personal or societal issues and interests, joys and sorrows, stories and inventions.

Some of Josef Albers' philosophical statements are both pithy and very relevant to every artist. For instance: "The content of art: Visual formulations of our reactions to life." Or: "The aim of art: Revelation and evocation of vision."

It is remarkable to think about the diversity of reactions to life shown by artists thought the ages and even more so today, in the wide-open world we all evolve in. It is testimony to both artists' individuality and their cohesion that the art created is often such a powerful evocation of their vision and that it can be understood and shared by such wide and far-flung publics.

The aspects of revelation and evocation of vision are tackled with many different means. Painting, video, sculpture, photography, drawing... are just some of the visual means. Drawing, for instance, my favourite medium, is a passport to exploring and understanding the world about us in potentially exquisite detail.

Artist, Australian Brett Whiteley, said something very wise about drawing: "(It)i s the art of being able to leave an accurate record of the experience of what one isn't, of what one doesn't know. A great drawer is either confirming beautifully what is commonplace or probing authoritatively the unknown."

Another interesting remark about drawing: "Every motion of the hand in every one of its works carries itself through the element of thinking, every bearing of the hand bears itself in that element. All the work of the hand is rooted in thinking." Convoluted but in essence, this remark of Martin Heidegger harks back to what Albers said about our reactions to life in art making.

Actually the artist's thinking involves a lot of effort even before the hand begins to draw or paint. The initial idea for the creation necessitates decisions about medium, support, size of work, choice of colour (or not), even to work in the studio or outside. The hand's actions then reflect all these earlier thoughts and decisions, even if the actual art is more visceral and seemingly spontaneous.

All serious art-making is underpinned by care and effort and, consciously or not, by thoughts and observations that add up to that artist's philosophy. Often these philosophies are not articulated as such, but sooner or later, each artist, talking or writing about creating art, will begin to enunciate these thoughts. Artists' statement, for instance, are a vehicle for these thoughts. (However, I recently discovered that there are websites where you plug in various characteristics of your art, your age, etc., and hey presto, you have a seemingly skilled sample of "arts-speak" that says everything and in truth nothing at all - the very opposite of thinking about one's personal artistic philosophy.)

Perhaps it is an indication of deepening artistic experience and - ideally - skill that an artist can talk coherently and interestingly about what moves him or her to create art, what is important, how it is achieved. Somehow it is part of our collective heritage that artists can talk of how and why their art forms part of the extraordinary continuum of creative endeavour that links artists and humanity in general down the ages.

The Power of a Line /

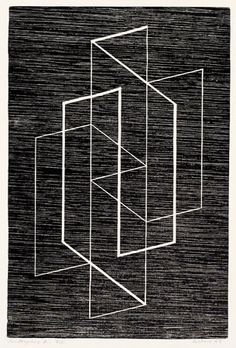

I saw a really interesting small exhibition that came from the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Bethany, Connecticut. It was at the Fundación Juan March in Palma de Mallorca and will be at the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in Cuenca from now until October 5, 2014. Josef Albers: Process and Printmaking (1916-1976) was a small exhibition, divided into three sections.

His first woodblock prints, in black and white, are a far cry from the vivid colours and abstractions of his later work in the United States.

Albers was first inspired by the coal mining landscapes of his native Northern Rhine-Westphalia region in Germany; he turned to print-making not only for its economy of production but also for the creative liberty that the medium allowed him.

He was deeply engaged, not only in the manual involvement of how art is made in the printing process, but also in the exploration of how far he could push the possibilities of the medium. Endlessly inventive and questing, he clearly kept saying to himself, “What if I did this – or that?”

Questions that every artist should be constantly asking him or herself.

One particular series was especially interesting to me, for it showed just how powerful each line can be in a drawing or print, and if one changes the emphasis of just one line, the whole composition and content of the work changes.

As Albers said, “Everything has form and every form has meaning”, and his simple series that ended as Multiplex A-D done in 1947-8, demonstrated that perfectly. Alas, his preparatory drawings which are in the exhibition don’t seem to be available on the Web. But even there, the progression of ideas and different emphasis each time on a principal line versus a secondary line underlined how Albers understood so well how art can be changed a great deal, even just by a thin or thicker line.

The preparatory drawings and studies for the Multiplex series ranged from pencil drawings on paper, then on tracing paper, sometimes using a red pencil for emphasis, sometimes a blue pencil.

Finally, having worked out the range of possibilities for that play of lines, Albers moved to studies on paper for each version of the series, then gouache over proof of a woodblock print.

Meticulous and yet questing, the preparation for such seemingly simple prints is instructive. Josef Albers had planned out exactly what he wanted to say, the emphasis each time on his view of each line’s importance. In other words, the more he prepared and thought about each work, the more pared down and powerful it became a lesson for us all!

These are the woodbock prints that are the results of the Multiplex series’ preparation.

Each line is eloquent and functions as a vital part of the composition, in a “major” or “minor key”.